by Greg Cailliet with help from others (26 May 2016)

This is a compilation of input from many MLML faculty, staff and graduate students, all of whom were involved in one way or the other with the operation of the museum at MLML. This is organized in chronological order. Much of the information was taken from some NSF proposals in past years to fund expansion and improvement of the MLML Museum (now called the Marine Biology Collection or MBC). Unfortunately, none of these proposals were funded and the MLML Museum is as successful as it is, mainly due to the hard work and dedication of past and present faculty and graduate students.

The MLML Museum is home to a herbarium collection of marine macrophyte (algae and plant) pressings, and many specimens of invertebrates, fishes, turtles, birds, and mammals. Much of this is in preservatives in jars, but there is also a fairly vast collection of dried specimens, bones, skins, and stuffed organism. This is a unique collection focusing on the biota of the Monterey Bay, collected during the last 50 years. It represents a thorough sampling of the flora and fauna of Monterey Bay and the larger sub-tropical and temperate Northeast Pacific region (Baja California, California, Oregon and Washington). It has proven to be a valuable research and teaching tool. Given the almost haphazard way in which the MBC was assembled, the procedures for accessioning, storage, care, observation, analysis, and loaning of MBC specimens have also been developed in an opportunistic fashion, and this will be part of the focus of this blog.

In 2009, many of the museum specimens in jars were used by local marine photographer, Jason Bradley, to produce some incredible images of deep-sea fishes and invertebrates (some images are interspersed in this blog). Jason has loaned MLML several large prints of these photographs and they hang in the hall near the Friends of MLML office (the Fangtooth, Anoplogaster cornuta), in the library (Krill, Euphausia pacifica, and the Longfin Dragonfish Tactostoma macropus), and one – a photograph of yours truly behind some jars of fishes in the museum – hangs above my desk in my home office. Jason Bradley Photographic is at P.O. Box 51621, Pacific Grove, CA 93950; phone: 818.415.2767.

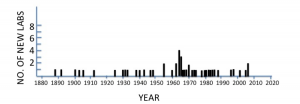

The MLML museum collection has a long history, going back to the first days in 1965 when MLML evolved as a California State College (now University) marine station in the Beaudette Foundation building. The idea of keeping representative specimens of local and west coast organisms for use in teaching and research was initiated by early MLML instructors, including James W. Nybakken and G. Victor Morejohn. Both of these instructors had considerable experience with museum specimens for their research and teaching. Indeed, the organization of the early card catalogue system was initiated by these two faculty members, along with others who were guest instructors (e.g. Jim Jensen - U.C. Berkeley, Peter Moyle -U.C. Davis, and Edgar Yarberry - Hartnell College).

Early Years

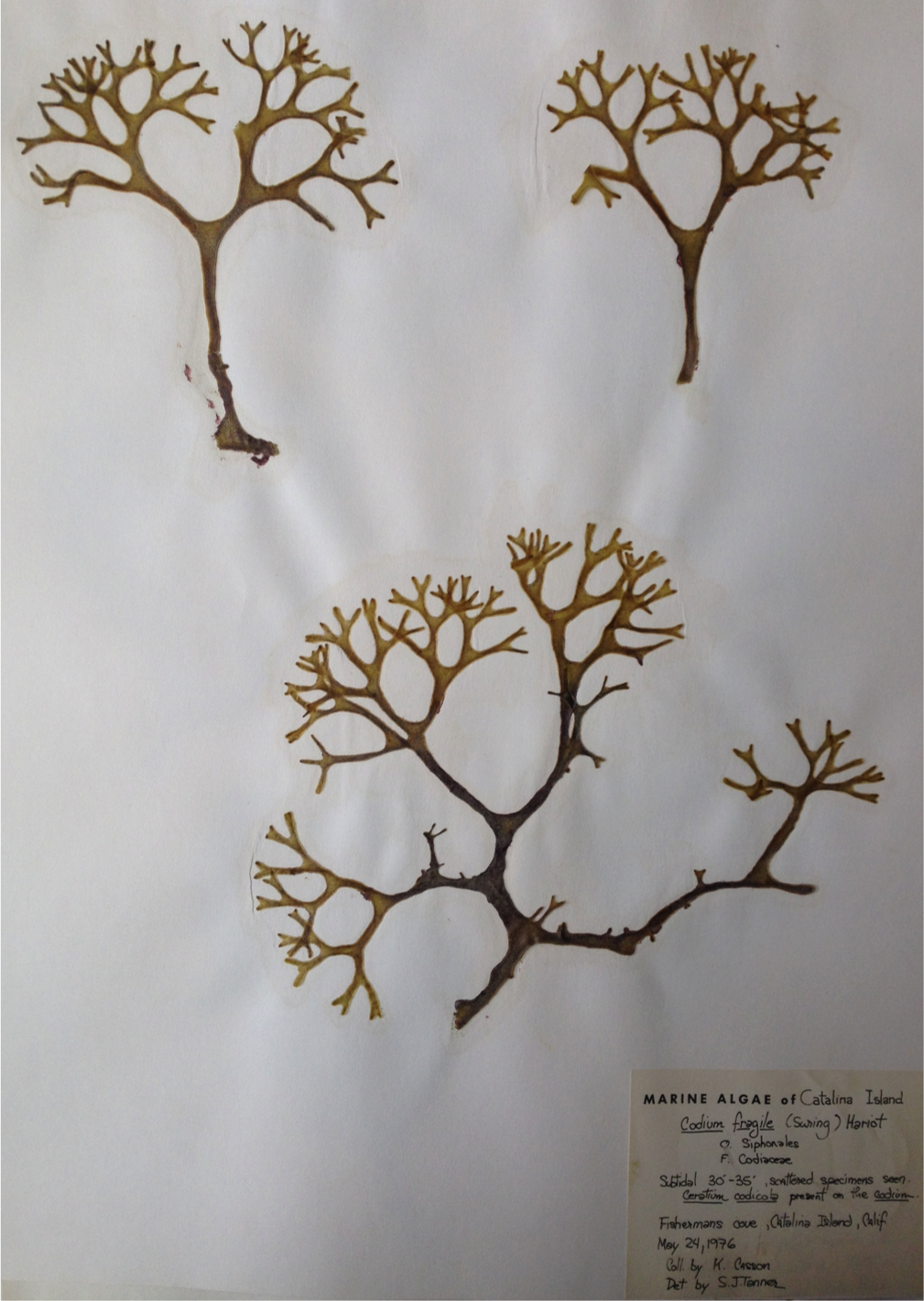

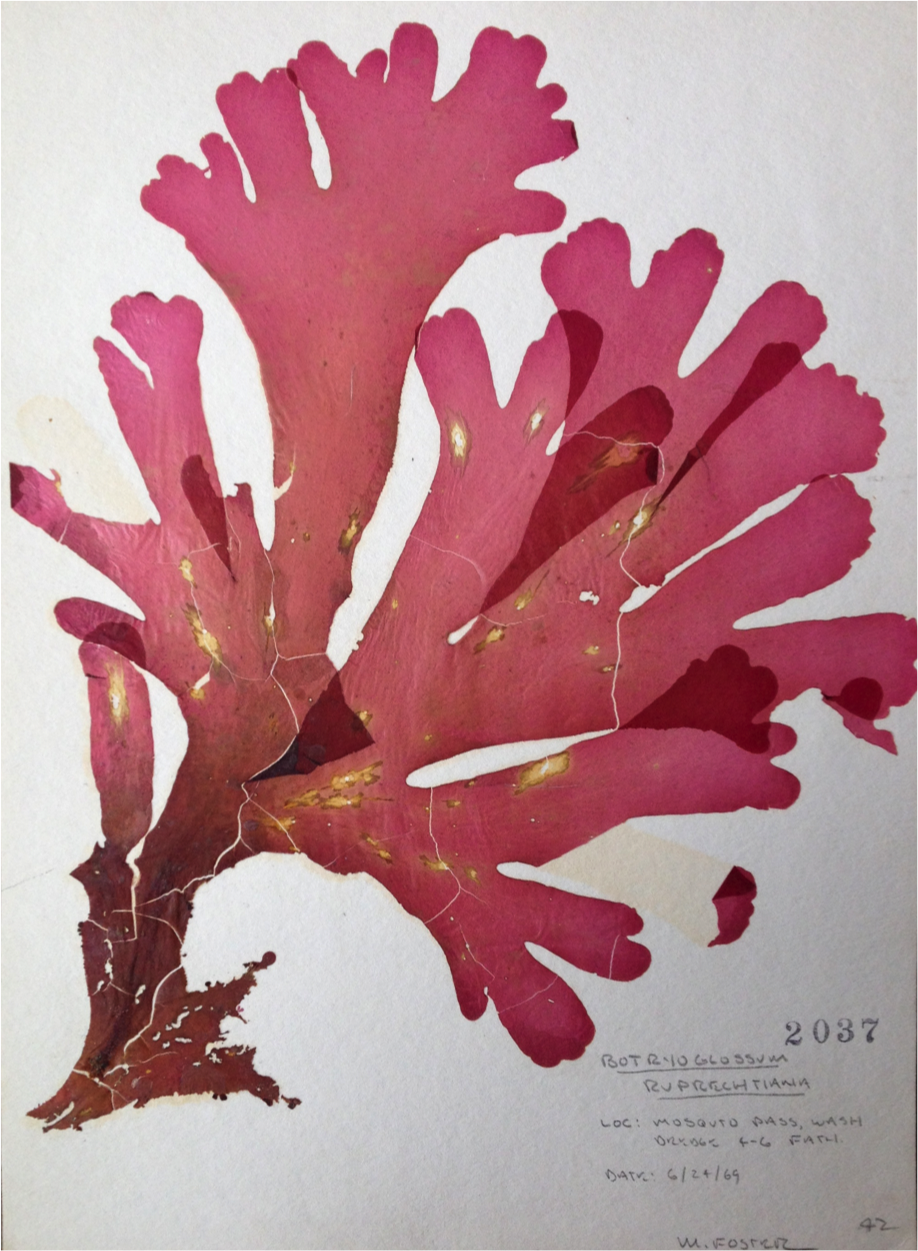

Phycology was first taught by Charles W. Bell (S.J.S.U.) in 1966 and later by Jim Jensen (U.C. Berkeley; Deceased), who is believed to have started the herbarium of pressed algae and some marine plants. Judy (Hansen) Johnson had a major role in the early herbarium collection at MLML. Judy was Jim Jensen’s TA. Jim was a traditional phycologist trained by J.F. Papenfuss from UCB, therefore, herbarium collections were of paramount importance in his classes. All students made class collections of 50 or more pressed/mounted local species from Monterey Bay. John Bell built a plant press dryer (the shape/size of a coffin) to continually dry the presses in the back of the classroom. The room smelled chronically like seaweed drying on the beach.

Judy curated the early herbarium collections. She used the labeling technique of the UCB herbarium and later that of Isabella A. Abbott (Hopkins Marine Station). Permanent herbarium specimens were mounted on 100% rag paper, therefore, should last for a 100 years. When Judy graduated in 1972, Sara Tanner and Lynn McMasters continued on with curating the herbarium.

John Hansen (FSU), Barry Turner, and Gary Davidson were the first graduate students of MLML in 1966 – working with John Harville. John worked on the boring shell symbionts/parasites of abalone with Jim Nybakken, and Judy believes that the large collection of abalone shells went into the invert collection. John and Barry worked closely with Vic Morejohn and Jim Nybakken in the early collection and accessioning of specimens of invertebrates, fishes, birds, and mammals.

Gary McDonald, who was a graduate student at MLML from 1970 to 1976 was put him in charge of the invertebrate collection by Nybakken after his first year, and he believes he was the first “official” curator of that collection. Shane Anderson collected a number of invertebrates for the museum during this time, including some during the R. V. Makrele cruise.

Fishes and Vertebrates:

Victor Morejohn apparently started the MLML museum, mainly for vertebrate specimens to be used for teaching. Gary Kukowski contributed some of the fish specimens to the collection during this time, while both Dan Varoujean and Larry Talent also contributed specimens from their field sampling.

Dan Varoujean, having collected birds for the Biology Department museum at California State University at Fresno prior to coming to MLML, applied his experience under the tutelage of Victor Morejohn and collected seabirds from 1969 to 1972, with many of these specimens being put-up as study skins for the museum by students under the supervision of Dan and Victor. Dan also collected Dall’s porpoise and retrieved marine mammal specimens that were cetaceans and pinnipeds found dead on the beaches of Monterey Bay. In 1971 Dan was awarded the salaried position of boat captain of the R.V. Orca and curator of the vertebrate museum. As curator, he continued to collect and prepare seabird and marine mammal specimens and prepared fish brought in by others for inclusion into the museum reference collection.

Dave Lewis said that his “recollections of his time as curator of the vertebrate museum at MLML are quite similar to Dan’s. He collected mostly seabirds and beach-cast marine mammals to add to the collection, maintained “The Boneyard” and provided skins and bones for Vic Morejohn’s marine mammals course. Dave said his “most difficult single assignment was to attempt to retrieve a rotting leatherback turtle carcass from the kelp bed off the DFG Granite Canyon lab (“I figured I could simply swim out, strap it to a dive mat and haul it in - I was lucky to just get the head!- Presumably it’s still in the collection.).”

In addition to the mostly humdrum duties at the museum, Dave performed necropsies for the California Department of Fish and Game (CDFG) on sea otter carcasses they provided, working with Morejohn and Jack Ames. They quickly established that several of the otters had apparently been hit by boats, based on the obvious blunt trauma and consecutive propeller slash marks. Their CDFG technical report was already in press when Jack, performing one last necropsy of a boat-battered otter, noticed a tiny serrated tooth fragment deep in one of the “propeller” slashes. The fragment proved to be from a Great White Shark (Carcharodon carcharias), and they had to scramble to amend their report accordingly.

1972-1983:

This was the decade during which new faculty were added at MLML and they had an influence on the MLML museum.

Tommy W. Thompson, from the University of Wisconsin, was added to the MLML to serve as the diving safety officer, the marine botany faculty member, and the MLML Sea Grant coordinator. Bette Nybakken recalls that he went on sick leave for the 1974 academic year she was hired to teach phycology for the spring and fall semesters. Bette had students make collections both semesters and accessioned some of those specimens for the Herbarium. And, she says “the herbarium was just one large cabinet in the classroom that year.” Sara Tanner was her TA both semesters, and, Jim Harvey was one of her students.

When Mike Foster came to MLML from CSU Hayward in 1976, Lynn McMasters was his T.A. for 2-3 years and added to the herbarium. Mike notes that Jim Norris added Gulf of California specimens, and Mike added pressed specimens of species from southern California and Puget Sound.

Gary McDonald continued to curate the museum until he left to work at U.C. Santa Cruz in 1976. Curation of the invertebrate collection was passed on briefly to Kathy Mawn, and then John Cooper (unfortunately now deceased) took over and had that job for some time.

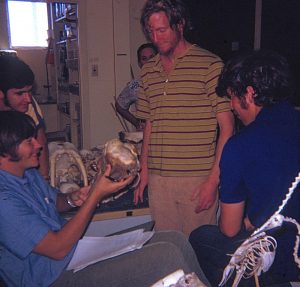

Gary provided a photo he took of the museum in April 1973, with a hand-held camera without a flash. So, it is not very sharp, but it is all we can find. In it, the formalin room is at the left rear, the fish collection in cabinets is in the aisle at right rear, the invertebrate collection in cabinets is at right & out of frame. The gray/brown cabinet at center rear might be the algae collection, but he was not sure.

James W. Nybakken always had an active interest in this collection. Between Jim’s and Greg Cailliet’s interests, there were many contributions, especially deep-sea midwater and benthic organisms, mainly from class cruises aboard the various research vessels available at MLML. The museum has a fabulous collection of deep-sea invertebrates and fishes (see also M. Eric Anderson’s comments later), some of which are fairly rare, and these have been used often by both MLML and outside researchers.

Gregor M. Cailliet started at MLML in the fall of 1972, and had experience with teaching and research collections of invertebrates and fishes at UCSB during graduate school. So, it was easy and interesting for him to take on the MLML museum fish collection. One of his first graduate students, M. Eric Anderson, took over as curator of the fish collection in 1973 and continued in that role until he graduated in 1977. Eric recounts that “At the start, the research collection consisted of less than 200 lots, the teaching collection was about 40 lots, and we had no dry skeletal, otolith, or larval material. The research catalogue was a card file started by Victor Morejohn and was a unique ecological system in which a specimen’s habitat or community was identified followed by a numerical indication.”

Eric’s research centered on midwater trawling in Monterey Submarine Canyon to attempt to keep mesopelagic critters alive in aquaria for study. He built a small midwater trawl with a special cod end to buffer the effects of hauling and was rather successful with some animals (midwater eelpouts, snailfish, one octopod, and shrimp). In addition, a lot of fish and invertebrate species from the Canyon were added to the museum from this effort, all trawled from MLML’s little tugboat, the R. V. Artemia (sometimes also known as the ST-908, its original name at Scripps Institution of Oceanography (SIO), and the Good Ship Lolipop, for its multiple colors).

With Greg Cailliet and John McCosker’s support and enthusiasm, Eric was mentored also by the curators at the California Academy of Sciences (CAS), Bill Eschmeyer and Tomio Iwamoto. Because of this, his objective as student curator was to build the research collection in terms of species and localities. This was possible through our own collecting and engaging in specimen exchanges with other museums, notably the British Columbia Provincial Museum. Specimens also were donated by collaborative scientists like Edgar Yarberry, John McCosker, and Bob Lea.

Eric also added that “A huge amount of enthusiasm and help in supporting my desire to build the fish collection goes to fellow students Brooke Antrim, Dave Ambrose, Rich Kliever, Gary McDonald, Ed Osada, my late wife Karen Anderson, and needless to say Greg Cailliet for his vision and financial support from some of his grants to expand the museum holdings. Thanks everyone, some great memories!”

Brooke Antrim remembrances: From the moment I arrived at ML in the fall of ’73, I knew I wanted to be involved with the Museum in whatever capacity I possibly could. At that time Gary McDonald was the Invertebrate Curator and M. Eric Anderson was the Fish Curator. The Museum was truly a cramped room of probably less than 400 sq. ft. housing 2 working desks, 2 prep sinks, 1 exhaust hood (story to follow), probably 2 cabinets of accessioning supplies and the rest of the space held all of the liquid preserved invertebrate and fish specimens. After three years of helping Eric with his duties when I could, in ’77 I became the Fish Curator when Eric left to pursue his doctorate.

Brooke continues: These were truly thrilling, exciting and vibrant years. The Collection was in its infancy, we were establishing protocols for preservation and accessioning, specimens were being donated by professional colleagues and other research institutions and almost every research cruise that put to sea provided some specimen that would end up being a new addition to the Collection. There was a sense of exploration that I can only imagine 19th century explorers must have held as they sought to sample ecosystems never touched by man. In fact during these years, the mid-water and deep-sea collection cruises were so diverse that several invertebrate and fish specimens resulted in new species descriptions. It would not be too much of a stretch to say that there was an adrenaline rush every time the net broke the surface of the water as to what secrets it would reveal.

Victor Morejohn continued to have a role in adding specimens of marine reptiles, birds and mammals to the museum. Lynn McMasters recalls taking Ichthyology and Birds and Mammals from Morejohn during one of the summer semesters in the early 1970s. She recalls preparing a bird study skin (probably still in the teaching collection) and a fish skeleton prep. The students got to take the skeleton preps home, but Lynn’s was eaten by her cat. Some students over the years used the “cat-ate-my-bone-prep” excuse for not turning theirs in for credit. Lynn was lucky that she got credit before her cat destroyed hers.

Roger Helm reports: “I was the Marine Bird and Mammal Curator/Lab Tech from 1977-78. I shared space in that dark, dank, and stinky museum in the original building with John Cooper (a really nice human being, may he rest in peace) who was the Invert Curator. The job was 1/4 time with the other 1/4 serving as the TA for Vic Morejohn's Marine Vertebrate and Marine Birds and Mammals classes. The essence of the vertebrate museum tech job was to head out at all hours of the day and night to retrieve dead birds and mammals, or parts thereof. When I arrived at the lab, my mentor for this job was a big-hearted gal who was so focused on delighting Morejohn with carcasses and specimens that she didn't have time for much else. I rapidly decided that if I was going to do this work I was going to stay upwind, dedicate a set of clothes and rain gear to the effort, and not miss a shower.”

Roger continues to say “It’s fair to say that Mike Rowe, star of the TV show Dirty Jobs, had nothing on MLML’s vertebrate museum techs. I wonder what he would have made of the opportunity to dissect a dolphin whose innards had been baking inside their thick blubber layer for days. While those dissections were not so sweet, they were a fresh ocean breeze compared to acquiring samples from a disintegrating 30-ton gray whale rolling around in the surf. Fooling with formaldehyde, mucking around in the bone yard, and attending to less than fresh flesh and oozing body fluids was not for the squeamish. For me it was great fun running around the bay and addressing fresh carcasses and when they weren’t fresh I attacked them with the battle cry Remain Upwind!”

Post-Earthquake Trailers and Warehouse in Salinas (1989-2000)

In 1989, MLML and the space that housed the Museum were destroyed during the Loma Prieta earthquake. Miraculously, almost the entire MBC and associated card catalog databases were salvaged. The specimens that survived the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake were removed by a group of students lead by Aaron King, who used a tractor to move boxes of specimens from the museum site on pallets. These were moved first to a building at the former Spreckles (Sugar) Plant, and then to a site in a warehouse leased by MLML and SJSU on Vertin Avenue, in Salinas, that was near the SJSU satellite campus that became the temporary home of MLML.

Erik Cordes recalls: “My first job at Moss Landing was during an undergraduate internship in 1993. I spent many an hour hidden away in Vertin organizing the collection from the U. S. Navy-funded dredge waste disposal study. It was where I first discovered the vast array of undescribed invertebrate species in the deep sea, a finding that changed my path and sent me into the deep sea (sometimes literally) for the rest of my career.”

In the mid-1990s, the collection was moved from Salinas to MLML’s Norte site and in some temporary buildings near a surf shop. Several former MLML graduate students had recollections. Ned Laman adds that the move to Norte was a big group effort, with many days of driving back and forth through the lettuce fields of Salinas with lumber, cutting up plywood, then anchoring the shelving system. Both Ned and Erik recall some good lunches at the Central Texan in Castroville on the way between Salinas and Moss Landing. Then the specimen jars had to be prepared for transport to the shore. Ned recalls that “moving day from Vertin Avenue was one where we called on “all hands” of the core grad student body at that time and had a dozen or more people over there putting jars in 55 gallon barrels with vermiculite.” Bill Leopold and Julie Neer also remember helping them, and others, pack the jars in 55-gallon drums with vermiculite, and then move the museum collection from the Vertin Avenue warehouse to the trailer at MLML Norte.

Wade Smith reports that he was also one of the students who helped with the next transition, moving samples from the trailer down at Norte to the new lab, and topping off fluids regularly before and after the move. He said “I recall doing quite a bit of packing and organizing in the trailer there on the beach with Jeff Field, perhaps with Joe Bizzarro, and they were involved also packing up inverts as well as fishes.

Before the move to the hill, Wade recalls that some of the Ichthyology Lab members spent a lot of time working in the little bit of space that was available in the museum trailer at Norte. He reports that “the fumes were horrible in that room. Jeff, Joe, and I had a class project on shiner perch and pipefish diet and we did all of our dissections and work up in that room.” He thinks that was part of their project in Steven Morgan's Larval Ecology class. So, even that full, stinky (mammal, formalin, alcohol odor) room saw a fair bit of use. Wade transitioned to working at the present site on the hill during the move in 2000.

New Moss Landing Hill Site Building (2000-present)

When we moved into the new, and present, MLML building up on the hill, the MBC was subsequently transferred to a dedicated 4-room museum on the new MLML campus. The specimens were organized into specific locations, helped a great deal by new compact shelves that had been installed in the southern end of the museum space.

Wade Smith stated: “I always enjoyed the teaching collection. A lot of samples were in poor condition after years in Salinas. It was exciting to see the nice racks go into the museum space (as it was open/empty space for quite awhile after we moved in).” He, and others, shelved the jars in the new museum on the hill (both invertebrates and fishes). Wade and Joe included some new specimens from Baja California. And, when the Pacific Shark Research Center was established, Dave Ebert's presence ramped up collection efforts and accessioning new specimens.

Since that time, growth of the MBC has accelerated due to use by researchers and students from MLML and beyond. It is used annually in 14 organism-based marine science courses at MLML. Data on fishes and invertebrates from numerous deep-sea and benthic trawling class cruises since the mid-1980s are stored on and available from the SIMoN (Sanctuary Integrated Monitoring Network, of the Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary (MBNMS) – see here for the Sanctuary SIMoN species database and associated data bases.

Specific voucher collections are also housed in the MLML museum. The include the following: – ACOE Collection, Cephalopod Beak Collection, ESI Reference Collection, Farallones Collection, Herbarium Collection, Hodgson Collection, Invertebrate Collection, Kaiser Refractories Collection, PG&E Collection, SWOOP Reference Collection, and the Slattery Collection. These can be found at the MLML Digital Commons.

Since our rebuilding, however, MLML researchers have also created four unique MBC research collections of worldwide importance: 1) the Global Kelp Archive; 2) the Pacific Shark Research Center's Chondrichthyan Taxonomy Collection; 3) a larval fish collection stressing local species; and 4) a collection of fish otoliths, cephalopod beaks, and other things useful for identifying prey of predators like larger fishes, birds, and mammals. These collections are the basis for long-term research programs that facilitate the research objectives of MLML faculty and students alike. As such, the MBC currently has two purposes: (1) maintenance and improvement of specialized research collections vital to studies of marine biodiversity, evolution, ecology, and conservation; and (2) maintenance and improvement of broad teaching collections essential to the organismal-training of marine science students.

Chris Rinewalt started putting the collection into a software program (Excel) that made it accessible, as Wade recollected wanting to do earlier. First, he and Aaron Carlisle went through all the class cruise (and other sample) data sheets for the SIMoN project. He said that sorting through the small binders of the old sampling sheets in the museum area was difficult. It involved trying to decipher the handwriting of students from 20+ years previous, along with their vague descriptions of sampling locations (or converting LORAN-C to Lat/Long), and scanning every available document (CTD casts, maps, drawings, etc.) into the database for eternal preservation. Unfortunately, the MBNMS folks at SIMoN did not use those metadata when they published it as an Access database on their website. And, now the important data are there, in both formats (Excel and Access) and available to all.

Also, when Chris Rinewalt worked in the museum while TA'ing for Ichthyology, he recalls many hours in the museum with the radio on, cataloging specimens and accessioning new entries. There apparently had been quite a back up from the trailer days and a lot of catch-up work had to be done. He reports seeing things he'd never seen before or since. He was very curious about the parts of whales and other mammals that were saved in 5-gallon jars. Chris’ main role was to update the museum collection in a state-of-the-art Excel spreadsheet. And, now those collection data are posted online, which comprises quite an upgrade. When Greg Cailliet retired in 2009, Scott Hamilton became the Ichthyologist, and has been active in getting the fish collection maintained and improved.

And, also in 2009, many of the museum specimens in jars were used by local marine photographer, Jason Bradley, to produce some incredible images of deep-sea fishes and invertebrates. Jason has loaned MLML several large prints of these photographs and they hang in the hall near the Friends of MLML office (the Fangtooth, Anoplogaster cornuta), in the library (Krill, Euphausia pacifica, and the Longfin Dragonfish Tactostoma macropus), and one – a photograph of yours truly behind some jars of fishes in the museum – hangs above my desk in my home office. Jason Bradley Photographic is at P.O. Box 51621, Pacific Grove, CA 93950; phone: 818.415.2767.

Jim Harvey re-activated interest in improving and adding to the bird, mammal, and reptile holdings of the Museum during this period. In the past several years, Catarina Pien has been doing a stellar job of improving the entire collection through maintaining fluids in the jars, photographing specimens, and making sure that the accessioning process and final resulting database are efficient.

Present Activities in the MLML Museum and How It Functions

Natural history collections (i.e. the collection and preservation of organisms whole or in part) are invaluable resources for biological research and teaching. They are snapshots of nature in space and time, and researchers from a variety of biological fields, from taxonomy to biogeography and paleontology, rely heavily on these collections to guide investigations into the evolutionary history of organisms and species.

Moreover, most ecological studies require that researchers not only have a good understanding of species identification, but that they know how to distinguish individuals of one species from another. It is natural history collections that facilitate proper species identification as well as an understanding of the spatiotemporal variability in organism form and condition. And, this natural history and taxonomic capability is something that is central to the education of both undergraduate and graduate students at MLML.

Improvements are occurring in the museum, including: 1) reorganization of specimens, primarily using compact storage units that more efficiently house specimens; 2) improving the care of specimens, including renewing preservation fluids, 3) updating of computer files on the holdings; 4) taking digital images of MBC specimens; and 5) maintaining a freezer storage unit of tissues for DNA sequences. This is presently being done by staff (Jocelyn Douglas) and student curatorial support, presently Catarina Pien and Heather Fulton-Bennett.

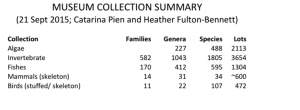

The MLML Museum contains at least 11,000 accessioned biological specimens, with ~75% housed in research collections and ~25% in teaching collections. The following is brief a taxonomic breakdown of accessioned specimens within the five taxonomic groupings representative of our faculty research and educational specialties.

In addition, there are otoliths from ~ 165 species of fishes, used for prey identification purposes, numerous lots of fish larvae, and a newly initiated frozen tissue collection.

In addition, there are otoliths from ~ 165 species of fishes, used for prey identification purposes, numerous lots of fish larvae, and a newly initiated frozen tissue collection.

This blog was a edited version, so if you want to read a full accounting of the history of the MLML museum by Greg Cailliet, please use this link.

3. Grateful Dead (apparently first played as Grateful Dead in San Jose, CA)

3. Grateful Dead (apparently first played as Grateful Dead in San Jose, CA)