By Mark Carr, Todd Anderson, and Mickey Singer (30 June 2016)

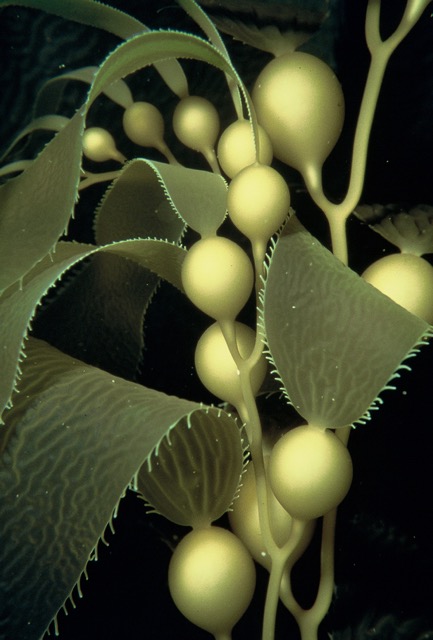

Over the years, Stillwater Cove in Carmel Bay has become one of the most well-studied kelp forests on the West Coast, thanks to the foundation of research established there by Mike Foster and the good graces of the Pebble Beach - Beach and Tennis Club. Mike taught a course in subtidal ecology at MLML for many years, and this was a springboard for considerable research involving scientific diving at Stillwater and other locations along the coast of California. The late 70s and early 80s were a heyday for kelp forest research at Stillwater. Among the many students doing thesis research at the time was a group of overly enthusiastic fish ecologists, bound and determined to unravel the importance of kelp forests as nursery habitat for rockfishes. At that time, when divers saw a juvenile rockfish, no one had a clue as to what species they were observing, let alone anything about their ecology. Mickey Singer, Guy Hoelzer, Todd Anderson, and Mark Carr became infatuated with the 10-14 species of juvenile rockfishes that occurred in the kelp forests of Stillwater Cove. These were formative years for learning the skills of scientific diving, boating, and subtidal field ecology.

Our treasured research vessel was a 16’ old Navy black inflatable, riddled with enough small holes that caused it to leak air continuously. Before, in between every dive, and before heading back to shore, the “black raft” was refilled with a dedicated SCUBA tank and a small hose. At one point, we were able to keep the inflatable moored in the water, which could be seen readily from members of the Beach and Tennis Club overlooking the cove, including MLML Director John Martin. Between dive days, the inflatable turned into a floating waterbed, much to the embarrassment of Dr. Martin, who reached the point of replacing the “black raft” with two new Zodiac inflatables for scientific diving at the lab.

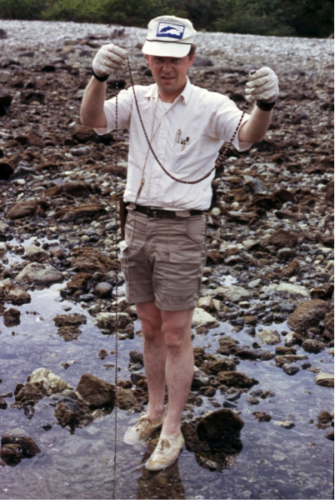

We developed a healthy respect for the ocean environment the hard way. Launching inflatables at Stillwater was a challenge with south-facing swells. On one particular occasion, several of us were launching a Zodiac through high surf. We had loaded everyone’s gear into a Zodiac and Guy was in the inflatable trying to start the engine as the rest of us were in the water walking the boat through the surf. As an unexpected wave approached, Guy dove on top of the gear in the bow to keep the Zodiac stable. Instead, he was launched into the air along with much of our gear, including SCUBA tanks. We spent some time searching for gear with our hands and legs, eventually finding most of it. Diving was also a challenge for some of us. One day Mark Carr left his wetsuit hood and booties at the lab and he made three dives in 8-90C water during upwelling with no hood and a pair of gloves on his feet. He returned to the lab wandering around the facility before heading home to spend the rest of the day in bed suffering from hypothermia. These formative “wise” diving practices prepared Todd and Mark for their current roles as the Chairs of the Diving Safety Boards of San Diego State University and UC Santa Cruz.

Aptitude for the logistics of field experiments was also gleaned from our studies at Stillwater. A large (36 m2) artificial kelp forest was secured to the bottom with sand anchors and line off Arrowhead Point. When it was time to remove this kelp forest, the R/V Ricketts cruised to the site. Before loading a crew of divers who rendezvoused on the beach to help remove kelp and retrieve the anchors and line, the Ricketts powered to the site only to find that the entire experiment had vanished. The ocean giveth and the ocean taketh away. However, the ocean wasn’t the only thing that taketh away. A close colleague working on adult kelp rockfish, Gilbert Van Dykhuizen kept deploying surface buoys to mark his study site at Stillwater, only to find them stolen each time he returned for another dive day. Finally, he found the ugliest buoy he could find (pink and green) and wrote “YOU TOUCH, YOU DIE!!” on it… only to find it too was gone by the next visit. Gil’s struggles with logistics were further confounded by an amorous harbor seal who simply couldn’t leave him alone underwater, dubbed Gil’s girlfriend.

In the end, we all completed our master’s theses, working on various aspects of the biology and ecology of juvenile rockfishes, including identification, distribution, habitat associations, timing of settlement, and behavior. We remember Stillwater fondly, as much for our experiences and camaraderie as for the research we accomplished. With the help of the faculty and students at MLML, we taught ourselves how to design studies, develop skills in scientific diving, build sampling gear, troubleshoot outboard engine problems, and of course, have a healthy respect for the ocean and its inhabitants. For us, this was a special time, and MLML was (and is) a special place.

Mickey Singer: What I remember most about doing research in Stillwater, aside from all those lovely beach launchings, was that when diving was good it was often really good, and when it was bad, well, you get the picture. Part of Mark Carr's habitat and my feeding studies involved crepuscular observations. Night diving in Stillwater added an interesting layer to the whole operation. Sitting in the Ricketts for hours between dives in wet wetsuits was particularly comfortable. There were nights when visibility was great, and the bioluminescence was amazing! And there were nights when the vis was lousy, and those mid-depth-open water transects had the distinct addition of the music from “Jaws” in the background. But all in all it was a great place to do research.