Rescuing the Seismic Profiler

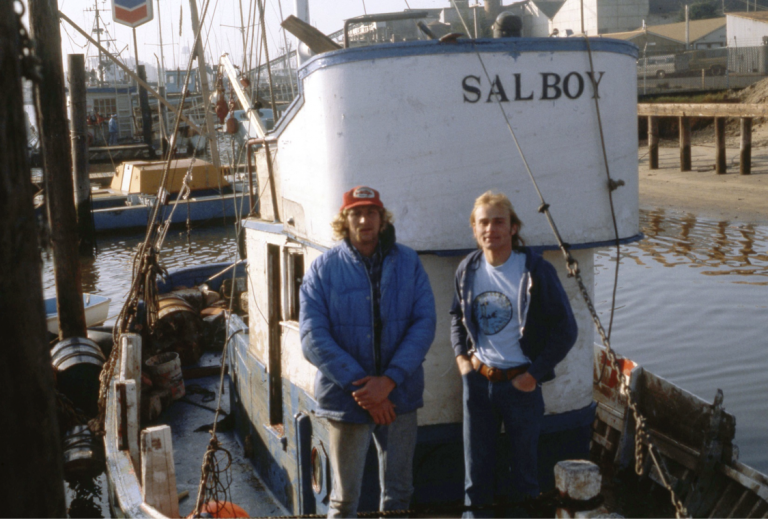

Around sunset on April 22, 1982, Dave Schwartz came running into the lab and was frantically trying to find help. Hank Mullins and Dave had taken a new seismic profiler out in a Boston whaler to examine the subtidal geologic features near the mouth of Elkhorn Slough. The apparatus was bulky and consisted of several parts kept in the boat and a large uniboom sled towed behind. Compressed air blasts from the uniboom are directed to the ocean floor, hydrophones receive the signals, and a geologic profile is generated through computer processing. On this day, the yellow and blue uniboom sled was trapped below the surface and the large black cable connecting it to the equipment in the boat was hung up on something underwater.

At 7:00 PM, there were few people still at the lab. I was the only diver and didn’t want to do a night dive in the harbor by myself. But Dave pleaded with me saying that Hank needed to be rescued because the tide was coming in and the whaler might sink. They would lose several thousands of dollars of equipment if they had to jettison it. I grabbed my dive gear, loaded it into a lab vehicle, and Dave and I headed over to the Highway 1 bridge. I jumped in the water from a dock at Maloney’s Harbor Inn on the northwest side of the bridge and started swimming parallel to the bridge to get to where the whaler was positioned. But almost as soon as I left the shore, there was a tremendous incoming tidal flow roaring under the bridge. It was so strong that I barely made it to the bridge’s first piling and just clung on. If I had missed that bridge support, who knows how far I would have been swept into the distant reaches of seven-mile Elkhorn Slough – at night!

Meanwhile, back at home in his house at Sunset Beach just north of the lab, Dave Nagel patiently waited for Hank and Dave S. to show up for dinner after their long seismic profiling field day. Dave N. had cooked a nice chicken dinner and became worried when the two researchers were well past their arrival time. Dave N. turned down the oven and headed to Moss Landing. When he drove over the slough, he saw Hank and the whaler hung up near the Highway 1 bridge. Dave N. stopped and walked on the bridge, called out, and saw that I was in the water with my SCUBA gear. Both Daves, now working together, threw me a rope.

Unable to swim against the very strong tidal current, I held onto the rope while my support team dragged me from piling to piling. Each time I let go of a bridge support, I disappeared and was sucked under the bridge until both men pulled me back out to the next piling. Eventually I got to the whaler on the channel side of the bridge. Then, while climbing into the whaler with all my dive gear, I lost my weight belt. Dave S. went back to the lab and got me another one. I then went down the cable attached to the uniboom and the bridle was caught on an old submerged wooden piling about 10 ft below the surface. The cable was also wrapped around a second piling that was deeper. I untangled the cable from both pilings and it floated free. We were now drifting in the current.

Weight belts were expensive and I came back about half an hour later with a dive light and searched underwater trying to find my weight belt while I held onto a line. Thirty minutes into this dive, the current had slackened and I found my belt. Dave Schwartz asked me to take two core samples at a depth of 30 ft under the bridge for his thesis and I obliged. Anything for science!

Eventually word got out about the calamity in the harbor and we had to face the music. John Heine, our Diving Safety Officer, mildly chewed me out for diving solo, but understood that I was in a tough position. Hank probably got the worst of it and received a rather stern dressing down from our director, John Martin. I felt proud that I had rescued the lab’s equipment, but acknowledged it was a dangerous stunt. Many things could have gone wrong, and almost did, but thankfully it all turned out well – except for the charcoal chicken dinner.