by Jason Gonsalves, MLML Physical Oceanography Lab

Eco-consciousness at first seems like an individual choice without wider implications. Working with Green Seal this past summer revealed the attachment of this behavior to anentire market through a process called ecolabeling. Green Seal generates “rigorous standards for health, sustainability and product performance” that aim to drive “permanent shifts in the marketplace, empowering better purchasing decisions and rewarding industry innovators.” As an intern in the Science & Standards Department with Green Seal, I witnessed both how widespread these labels are, and how companies concern themselves with being portrayed as ‘environmentally friendly’, so much so that they’d pay to be certified by ecolabeling nonprofits like Green Seal. At a moment where conservation of the environment is increasingly more popular and desired, I began to wonder about how valuable science (and by extension conservation) is to the economy.

A 2020 report from Gutleber states that “science and technology underpin much of the advance of human welfare and the long-term progress of our civilization.” The focus of Gutleber’s report is on the efficacy of investing in particle physics, noting “large-scale instruments can also offer positive returns for the economy and society as well as many opportunities for industry and enable co-innovation through international collaboration.” However, these benefits could be extended to other scientific operations as innovation expands in other disciplines. Has the expansion of science into the mainstream world created market value for scientific interpretation?

Does scientific advancement generate revenue?

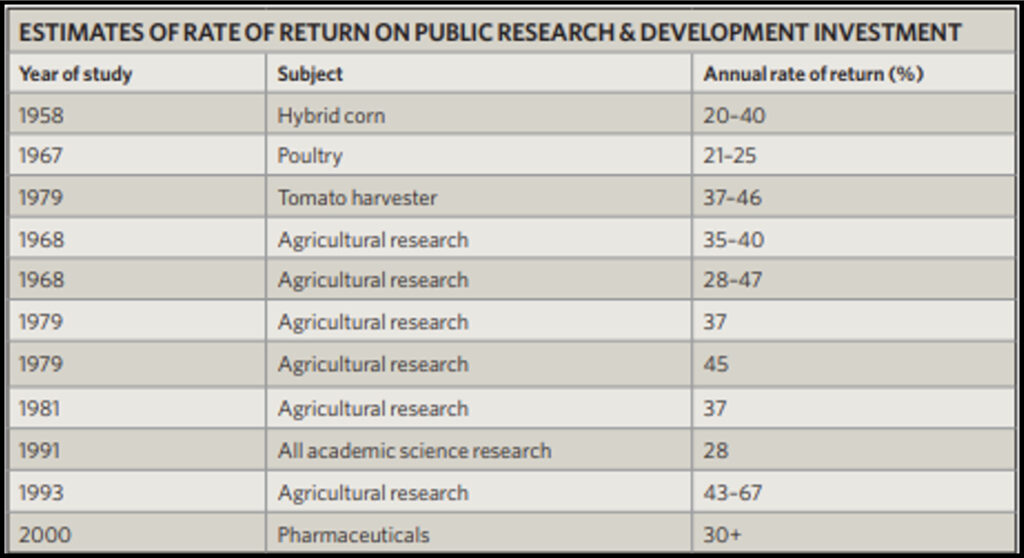

Globally, there are research initiatives that are contributing considerable economic growth. Examples of this are organizations like the National Institute of Health (NIH), which generates $2.21 in additional economic output for every $1 spent on biomedical innovation. In Australia, government analysts released a report in 2015 recognizing around $145 billion a year in revenue from innovation in science and research.

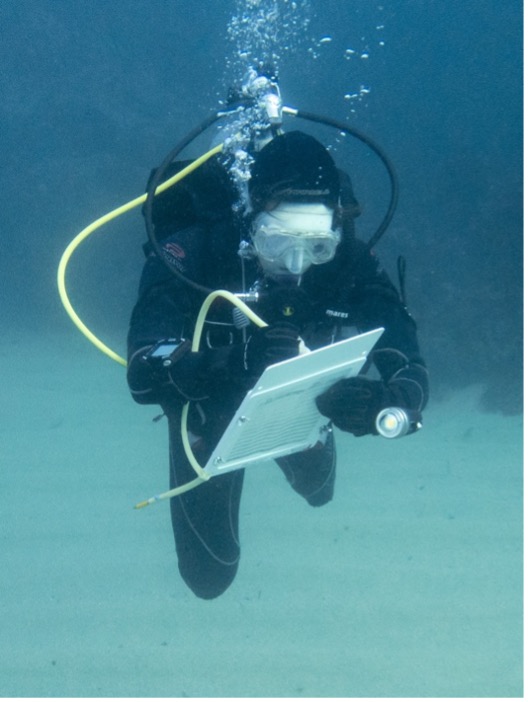

Other than direct production from research endeavors, improvements in scientific fields have led to the preservation of assets in world resources. A 2015 World Wildlife Fund (WWF) report estimated ocean assets (i.e. fishing, aquaculture, tourism, education, shipping) totalling over $24 trillion in value. Anthropogenic effects like habitat destruction, pollution, overfishing and climate change have begun to chip away at that value. Advances in ocean sustainability, coastal management and new technology are crucial to maintaining the value of critical resources like the ocean.

The business perspective on science

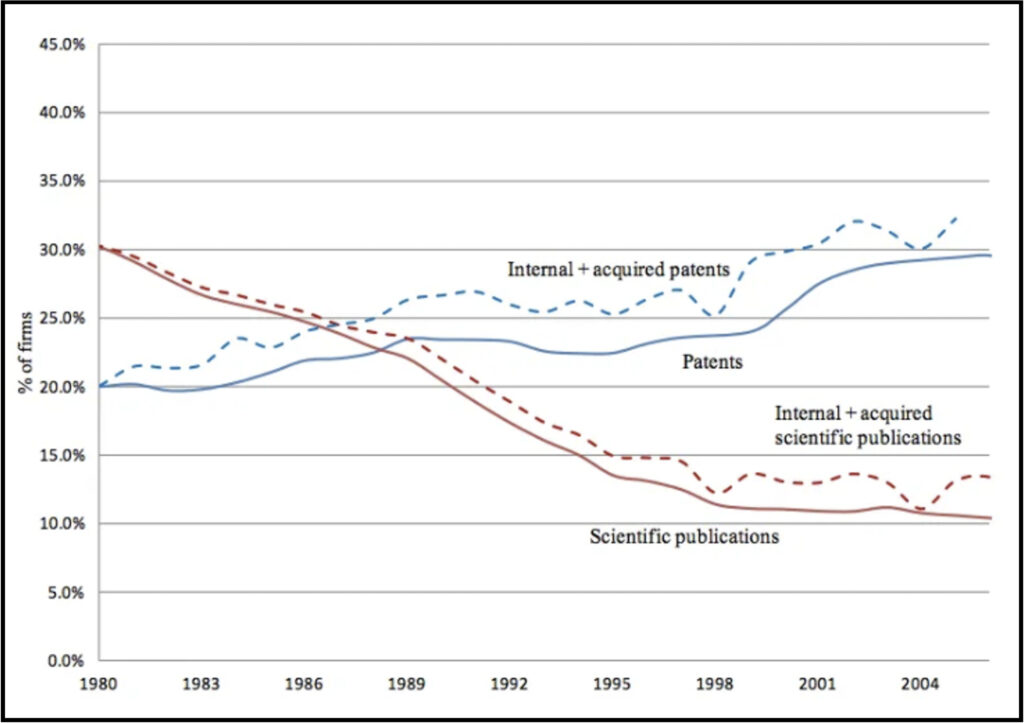

Investment into scientific innovation is clearly profitable, and the numbers show that the corporate world should build this into their framework. However, over the past 30 years, there has been a considerable decline in corporate R&D on basic research concepts as opposed to late stage development. A National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) 2015 report found that companies are still patenting new products, but those patents are being acquired from other places.

It seems corporations have become more interested in the products of science as opposed to scientific applicability. Large-scale R&D has been beneficial to society, but there is a possibility that it is not commercially viable. Looking at it from a business perspective, the biggest obstacle is the viability for shareholder returns. It’s clearly imperative that not only the United States, but the world not lose sight of the importance in advancing scientific discovery. How do we pitch investing in science more effectively to corporations?

Reinvigorating the corporate conversation on scientific innovation

The same Australian study concludes that in societies with an ‘advanced’ economy (i.e., a high standard of living), science underpinned 10-15% of economic activity. In order for continued economic growth, the logical undertone would be that science and technology will require further development. To return to an age of rapid scientific progress and innovation, the conversation must be approached from both an academic and economic standpoint.

Academia has long been considered an ‘ivory tower,’ and accessibility to information from non-scientists has been difficult for a number of years. This mentality created a gap in trust and accountability between the public and scientists, but recent data shows that could be changing. Pew Research Center’s 2020 polling data shows that 73% of Americans believe science has positively impacted society, and 82% expect future developments to also be impactful. Public confidence in scientists has also increased, the same data noting 35% of Americans fully trust scientists (up from 29% in 2016) and 51% have a fair amount of trust for scientists.

Academia has long been considered an ‘ivory tower,’ and accessibility to information from non-scientists has been difficult for a number of years. This mentality created a gap in trust and accountability between the public and scientists, but recent data shows that could be changing. Pew Research Center’s 2020 polling data shows that 73% of Americans believe science has positively impacted society, and 82% expect future developments to also be impactful. Public confidence in scientists has also increased, the same data noting 35% of Americans fully trust scientists (up from 29% in 2016) and 51% have a fair amount of trust for scientists.

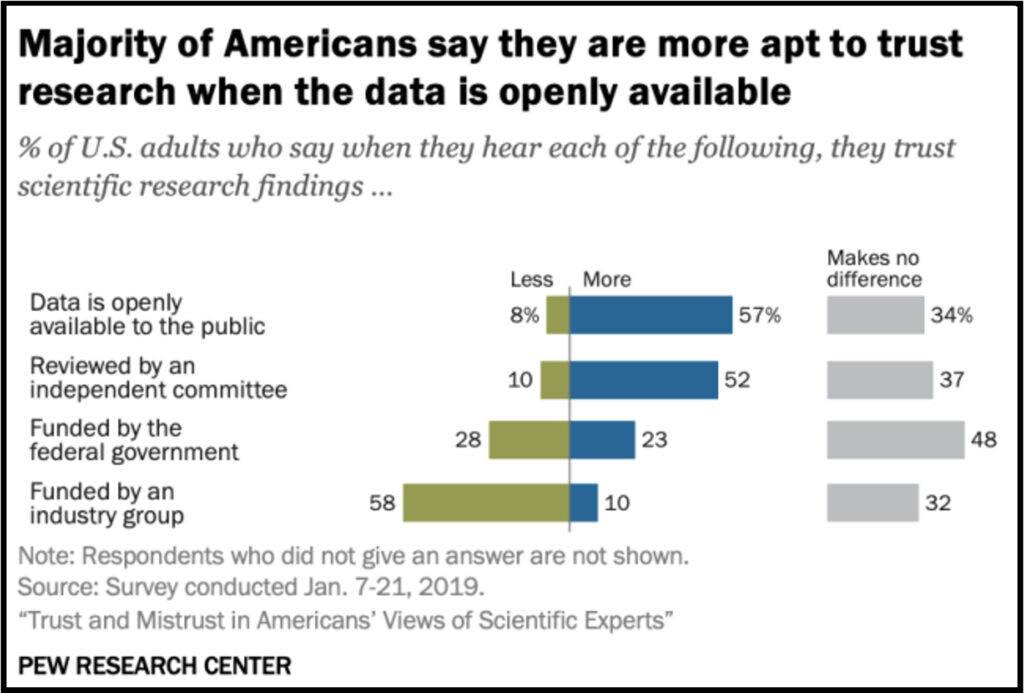

There is still more work to be done about the transparency of science, however, with that same 2020 polling data showing two-in-ten or fewer Americans don’t believe scientists are transparent about their conflicts of interest, and less than two-in-ten Americans believe scientists admit and take responsibility for their mistakes. This seems to be remedied in the study, with 57% of Americans saying they trust scientists more when data is publicly available.

Solving the divide between the public and the scientific community should restore scientific advancement to the forefront of social and economic development. Only time will tell if the efforts scientists are currently making will be enough to shorten that gap.

By Arie Dash,

By Arie Dash,

By Jason Gonsalves,

By Jason Gonsalves,  By Bri Sotkovsky,

By Bri Sotkovsky,  By

By  By Erick Partida,

By Erick Partida,  By

By  By Kameron Strickland,

By Kameron Strickland,