By Allie Margulies, SFSU Estuary & Ocean Science Center

By Allie Margulies, SFSU Estuary & Ocean Science Center

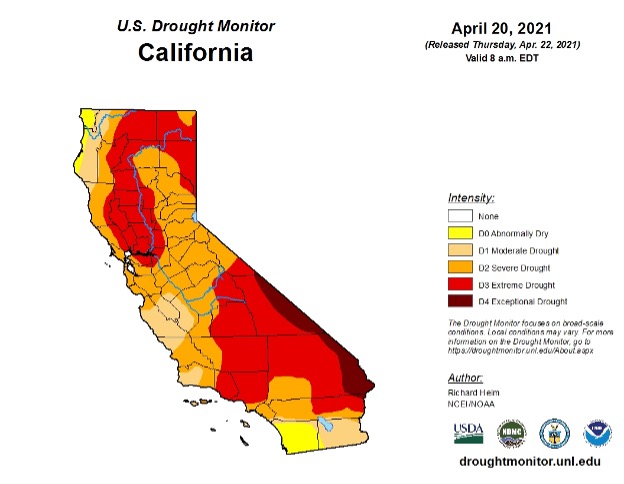

Looking back on the past few years, it feels as though Californians have faced a climate related crisis almost every year, whether it’s related to floods, fires, or drought. Within the past decade, many of us have become increasingly aware of our water usage after experiencing one of the most extreme multi-year droughts on record from 2012 to 2016. Then, in 2017 we experienced a record-breaking flood year. Now we are officially in another drought (Figure 1). Personally, I know I have made many permanent changes to my daily life in order to save water, such as making more informed food choices and taking shorter showers. Unfortunately, our problem is likely to get worse.

An Age of Extremes

While California naturally experiences a lot of variability in rain from year to year and month to month, climate change modelers (Swain et al. 2018) project that this variability is going to become even more extreme. Both drought and flood years are likely to become more frequent, and we may already be facing increased likelihood of these extremes. This is because climate change is causing changes in temperature and atmospheric circulation that affect the amount of pressure and water vapor in the atmosphere, altering rainfall patterns. This variability can affect our daily lives with road closures and flooding during high rainfall years, and by forcing us to ration our water during dry years, increasing tensions between agricultural and environmental uses. Both flood and drought years can cause millions or even billions of dollars of damage and economic loss.

Drought

Climate change models predict that unless we curb greenhouse gas emissions, we can expect to see extremely dry winters over 80% more often in Northern California and over 140% more often in Southern California starting in only about 30 years. However, climate change projections also show that we will see an even bigger increase in extremely wet winters. While this comes with its own set of problems, it at least improves the likelihood that our multi-year droughts will get cut short by a heavy rain year. This could help relieve tensions between environmental and agricultural groups and help give us a temporary sense of security.

Flooding and Rainfall Seasonality

I may have made flooding sound like a good thing above, but trust me, it’s not. Remember in 2017 when we got so much rain that the Oroville Dam’s primary spillway failed and necessitated the evacuation of nearly a quarter of a million people (Figure 2)? Winters with a comparable amount of total rainfall are expected to increase in frequency by 100 to 200% during this century alone.

Despite little overall change in average rainfall, our already short rainy season is projected to become even shorter. We can expect up to 40% more rain to fall in January and February, and up to 50% less in September and May. This means that during winters with high rainfall we will be getting even more rain in a shorter amount of time, increasing flood risk. By 2060 we are more likely than not to experience at least one flood beyond any level that our modern water infrastructure has ever experienced. This would likely cause substantial loss of life and nearly a trillion dollars in economic damages. The shortening of the rainy season also means we will have a longer fire season with less chance of being saved by early rains in the fall. While so many Californians have already experienced intentional power outages or had to evacuate their homes in the last few years because of fires or floods, it seems only logical to expect this to become an increasingly normal part of living in the Golden State.

Water Storage

With heightened extremes in water availability, water management will be increasingly important as climate change progresses. Increasing temperatures and drought years are reducing the amount of snowpack in the Sierras, which has important implications for our water supply. Snowpack works by storing snow that falls during the winter and releasing it as water when it melts in the spring and summer. However, over the past few decades snowpack in the Sierras has begun to melt earlier, in addition to getting less snow during increasingly frequent drought years. Snowpack has historically accounted for up to a third of California’s seasonal water storage and is extremely important to having a stable and consistent water source because it naturally regulates water supply throughout the year. Now we need to find another solution to get us through longer dry seasons and more extreme drought years. As we lose this form of water storage, we may need to rely increasingly on other options, such as groundwater, which is experiencing many issues of its own. As we see more frequent flooding, investments in infrastructure that redirects flood water to maximize groundwater recharge could provide a storage source to help get us through increasing droughts.

Technological Advancements

One innovation to help with drought years is to produce water through desalination, the process of converting saltwater into freshwater. This can be a controversial topic, yet California alone already has several desalination plants. While some Californians may value the added water security, desalination comes with many harmful environmental effects, sometimes at double the price tag of traditional water sources. Desalination is the most energy-intensive way to provide water, meaning that it would contribute even more to climate change, exacerbating the problem. It can also suck up marine life into the pipes, as well as cause dead zones in the ocean by excreting exceedingly salty wastewater. California’s Ocean Protection Council recommends that desalination “should be considered a future water source where it is economically and environmentally appropriate” as part of a balanced water supply portfolio, but that water conservation and water recycling should be encouraged as much as possible. Where desalination is deemed economically and environmentally favorable, projects can be improved with appropriate site location, facility design, technology, and mitigation to offset impacts. Personally, it is my opinion that we should be innovating technology to save water, not to create more in a process that would be environmentally destructive and contribute further to climate change. However, as climate change progresses, we may run out of options.

What you can do

I know this information paints a bleak picture, and this is only the tip of the iceberg. There are so many more ways in which climate change will affect us in California. As California faces more droughts in addition to water supply and storage challenges, here’s what you can do to reduce your water footprint. First, the most important thing you can do is to support policymakers and policies that are serious about climate goals and preparedness.

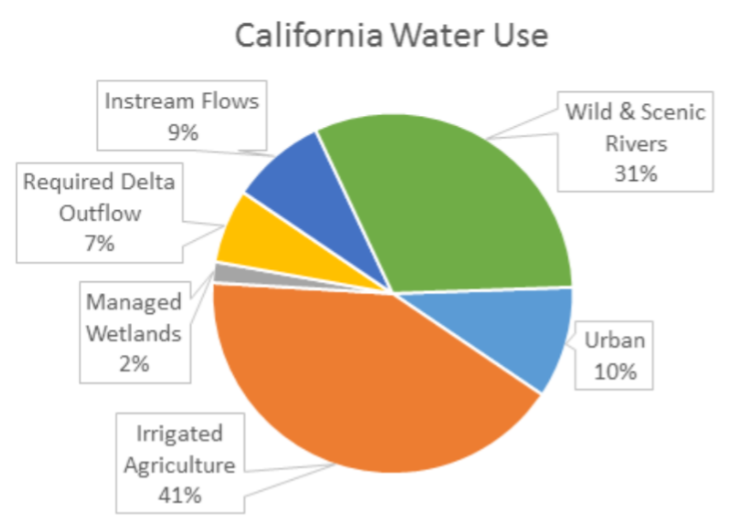

On a more personal level, it can be easy to feel helpless about climate change, and while it’s really important to reduce your greenhouse gas emissions directly (driving less, etc.), it’s also really important to make informed food decisions! Despite California’s naturally dry climate, US Geological Survey reports that we use more water than any other state, which is due in large part to our enormous agriculture industry that produces two-thirds of America’s fruits and nuts. On average, agriculture accounts for 80% of California’s water usage, not counting flows left for environmental uses (which make up about 40% of the total) (Figure 3). This means we can make a big impact by using our money to support more sustainable foods and sustainable farming practices that minimize water usage. For most people, our food makes up at least half our personal water footprint and is one of the best ways we can make an impact. To see how you’re doing, I recommend going to foodprint.org/quiz.

Much of the farming community has been working to improve their efficiency, and we can continue to encourage sustainable agriculture by not financially supporting the most water- and greenhouse gas- intensive foods. This doesn’t have to be a full commitment if you’re not ready. It’s easy to take baby steps and choose more sustainable food, even if it’s just once a week, and make sure not to waste food you’ve already purchased. You can also find out your total water footprint and see where you personally might be able to reduce your water usage at watercalculator.org.

Small changes can add up to make a big impact. I know it’s cheesy, but it’s true that if everyone makes a little change, it really can make a big difference.