By Jason Gonsalves, MLML Physical Oceanography Lab

By Jason Gonsalves, MLML Physical Oceanography Lab

You don’t have to be actively involved in the larger national discussion to know that climate change is an increasingly sensitive topic, even in 2021. As unbelievable as it may sound, the chances of someone in your social circle not being under the impression that global warming is happening are shockingly high. In a 2020 survey, an estimated 72% of Americans think global warming is happening right now. When adjusting to a more specific question, that same survey showed that only 57% of Americans believe global warming is occurring as a result of human activities.

Access to information has expanded rapidly over the last couple of decades, so why does it seem like the general public is so divided in understanding and addressing climate change? According to the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) in 2014, about “97% of climate scientists have concluded that human-caused climate change is happening.” There’s a clear scientific consensus on anthropogenic forcing affecting our global climate. Why have we reached such a crucial point in time where science communication just doesn’t seem to be cutting it? The answer may lie in the way in which we associate our own personal biases with scientific interpretation.

What’s going on with climate change? A brief summary

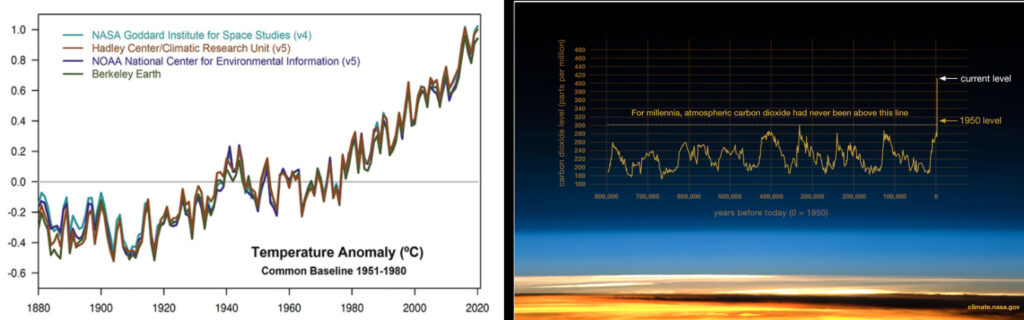

The overwhelming consensus of scientists on climate change impacting our planet right now is based on compelling evidence from a number of factors. The most prevalent is the rapid increase in global temperatures, which is largely attributed to the overall increase in atmospheric CO₂. A compilation of evidence displayed from NASA’s Earth Sciences Communication Center (ESCC) shown here shows “average surface temperature has risen about 2.12 degrees Fahrenheit (1.18 degrees Celsius) since the late 19th century, driven largely by increased carbon dioxide emissions into the atmosphere and other human activities.” Alongside general warming trends, other alarming impacts include glacial retreat, sea level rise, warming oceans, more extreme weather scenarios. These damaging changes to the global climate also affect general human activity and production, with the United States National Climate Assessment Reports (NCAR) here noting rising temperatures “affects agriculture productivity, energy use, human health, water resources, infrastructure, natural ecosystems, and many other essential aspects of society and the natural environment.” Among numerous other studies and filings, there is clear and immediate danger in letting climate change run rampant over the course of the next century.

The evidence points to climate change happening right now - why is there still lots of uncertainty?

While there is a clear and present scientific consensus on the effects of climate change, there is no active mitigation that can occur without the support of the general socio-economic structure (especially in the US). It has been increasingly difficult to pursue these lines of communication, to which those who actively support combating climate change have attributed to a lack in scientific understanding. However, recent studies in social sciences and scientific study have yielded some interesting insight.

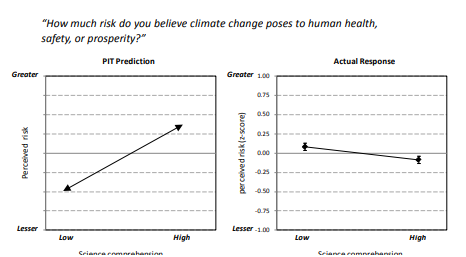

A 2014 paper from Kahan breaks down the different approaches to determining what’s clouding the perception of climate change. Kahan addresses the idea that there is a general lack of scientific understanding in comprehending climate risk in a national survey index from US adults. In social sciences, this is referred to as “public irrationality theory” (PIT). Kahan’s survey study asked US adults what their perceived threat of climate change was (low to high), and then administered a scientific literacy test based on scientific comprehension indicators from the National Science Foundation. Shockingly, the survey correlated somewhat negatively; US adults having moderate to high amounts of scientific literacy actually somewhat thought climate change was a lower immediate risk.

If scientific literacy doesn’t equate to higher perceived climate risk, then what separates the climate change ‘believers’ versus the climate change ‘deniers’?

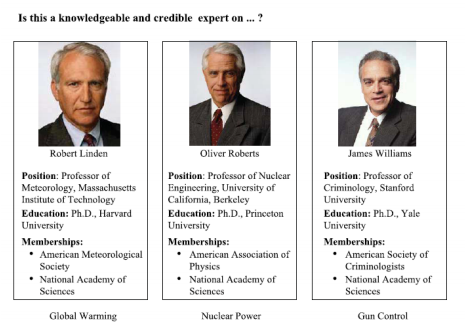

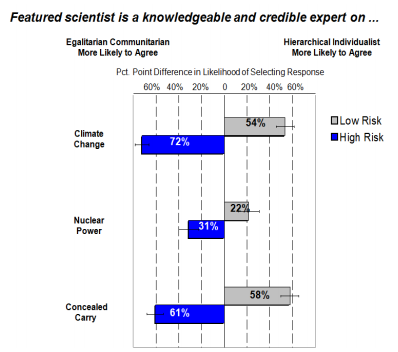

An analysis of the second leading theory known as the “motivated reasoning thesis” (MRT) shows a stronger correlation with inherent perception of climate risk. Kahan notes this theory is defined by when the individual chooses to “selectively credit or discredit evidence in patterns that reflect their commitments to important or self-defining groups.” In a similar survey study, US adults with different ‘worldviews’ were asked if several scientific experts were knowledgeable and credible on polarizing national topics (climate change, nuclear power, concealed carry). These opposing views were defined as ‘egalitarian communitarian’ (a greater concern for all individuals being equal, and taking pride in a sense of community) and the ‘hierarchical individualist’ (defined by the individual, where individuals are only capable of what is in their designation in a structured society). There was a clear association between belief in the experts in the community-centered egalitarian communitarians (which, coincidentally, most Democrats identify as) and disbelief with the hierarchical individualists (which would be more representative of Republicans).

An analysis of the second leading theory known as the “motivated reasoning thesis” (MRT) shows a stronger correlation with inherent perception of climate risk. Kahan notes this theory is defined by when the individual chooses to “selectively credit or discredit evidence in patterns that reflect their commitments to important or self-defining groups.” In a similar survey study, US adults with different ‘worldviews’ were asked if several scientific experts were knowledgeable and credible on polarizing national topics (climate change, nuclear power, concealed carry). These opposing views were defined as ‘egalitarian communitarian’ (a greater concern for all individuals being equal, and taking pride in a sense of community) and the ‘hierarchical individualist’ (defined by the individual, where individuals are only capable of what is in their designation in a structured society). There was a clear association between belief in the experts in the community-centered egalitarian communitarians (which, coincidentally, most Democrats identify as) and disbelief with the hierarchical individualists (which would be more representative of Republicans).

Kahan notes that it’s important to engage in “imaginative conjecture informed by valid decision science,” but that results must always be recognized as not “‘scientifically established’ conclusions but rather plausible hypotheses that merit testing by valid empirical means.” Placing yourself in a position of factual certainty against another who is not as well versed in the scientific dogma can prove to set you aside as being commanding and degrading as opposed to being informative and directional.

Kahan notes that it’s important to engage in “imaginative conjecture informed by valid decision science,” but that results must always be recognized as not “‘scientifically established’ conclusions but rather plausible hypotheses that merit testing by valid empirical means.” Placing yourself in a position of factual certainty against another who is not as well versed in the scientific dogma can prove to set you aside as being commanding and degrading as opposed to being informative and directional.

The future of science communication

Kahan’s study observing patterns in association of scientific information leads to some compelling conclusions. If there’s any hope of developing and implementing plans to combat climate change, we must understand the way individuals think. Providing the average citizen with as much presentable evidence as possible and letting them draw their own conclusions is a promising start. Letting the individual be pursuant in understanding the world around them is fundamental to developing their understanding, and scientists should move forward with a sense of personal understanding and thorough vetting of their communications and outreach.