By Erin Loury (28 September 2015)

Open House is one of my favorite memories of Moss Landing Marine laboratories, and my favorite memory of Open House by far is the puppet show. Puppet show? You could see the skepticism on the faces of some adults and teenagers hearing about this must-see event at a marine lab! But by the end of each day, word of mouth had spread, and many a parent told me they enjoyed the show as much as their kids. I think the puppet show really captures the whole spirit of the MLML Open House: the ocean is an amazing place, and anyone can enjoy learning about it.

I puppeted four shows at MLML between 2008 and 2011, and it became an event near to my heart. It was a chance for hardworking scientists-by-day to unleash a creative streak, and to become performing stars for a weekend. The shows were always a big group production, with numerous students and staff pitching in their various talents, whether it was writing songs, painting elaborate backdrops, stitching up new puppets, or rigging others with blinking lights. It’s seriously impressive how much artistic expression can be squeezed out of the personnel of a marine lab!

A puppet show is a pretty sneaky way for slipping a healthy dose of science into entertainment, whether it was about fish life history or taxonomy, the vertical migration of plankton, or adaptations in the intertidal or deep sea. We added corny jokes at every opportunity, and packed in as many marine science-y references as we could manage. Talking about Darwin’s Voyage of the Beagle? Perfect time for Snoopy to make an appearance. Got a chiton on stage? Cue the song “Low Rider.” I could go on…

Here is a link to a video of the 2014 Puppet Show on Ballast Water: http://islandora.mlml.calstate.edu/islandora/object/islandora%3A1713

The shows took place behind a simple wooden stage that has been used for years (and which we somehow always forgot how to assemble), but we really snazzed it up with handcrafted backdrops. During my first puppet show, one of the veteran performers was set on a crazy idea: a rotating backdrop that would take our protagonist Rocky the Rockfish through a series of random locations, from Paris, to Surf City Coffee, to Sponge Bob’s pineapple under the sea, on his journey from the open ocean to the kelp forest. Somehow we managed to pull it off, thanks to some great in-house artistic talent and crude engineering. And suddenly the puppet show production bar had been raised.

The plots of the show seemed to get more elaborate every year, and the backdrops along with them. There was the year we traveled through the pipe system into the Monterey Bay Aquarium and then back out to sea, and the year we went 3D and constructed an intertidal zone covered with egg carton barnacles and cellophane seaweed. Backdrop crafting was a group event, and even if most students had no desire to perform in front of a crowd, they could usually be roped into painting a kelp forest for an hour or two. Call it paint therapy.

As Open House drew nearer, I always seemed to have the puppet show on the brain. One year, our villain the evil sea star needed a shrink ray for threatening to take over the world (naturally). While cleaning up in the seminar room kitchen one afternoon, I noticed a drain snake lying next to the sink. Shrink ray found. I’ll never forget the look on caretaker Billy Cochran’s face when I asked him if I could borrow it for the puppet show. I think it made an appearance two years in a row.

But what really made the puppet show such a knockout were the songs. Every year we’d write new science parodies to popular tunes (and also sometimes recycled a few of our favorites). Bon Jovi could always be counted on for a show-stopping ballad—there was “Vertical Migration” about plankton set to “Living on a Prayer” (it worked somehow), and “Don’t Stop Clinging” about animals of the intertidal set to “Don’t Stop–“ well, you know how it goes

I have to say our most impressive lyrical feat was penning a song called “Chemoautotrophy” about deepsea tubeworms set to Beyonce’s “All the Single Ladies.” It was one of those songs that seemed to write itself while we sat batting around ideas in the student lounge. I will always love the audience that broke into applause as we did our best imitation of Beyonce’s signature moves while performing it.

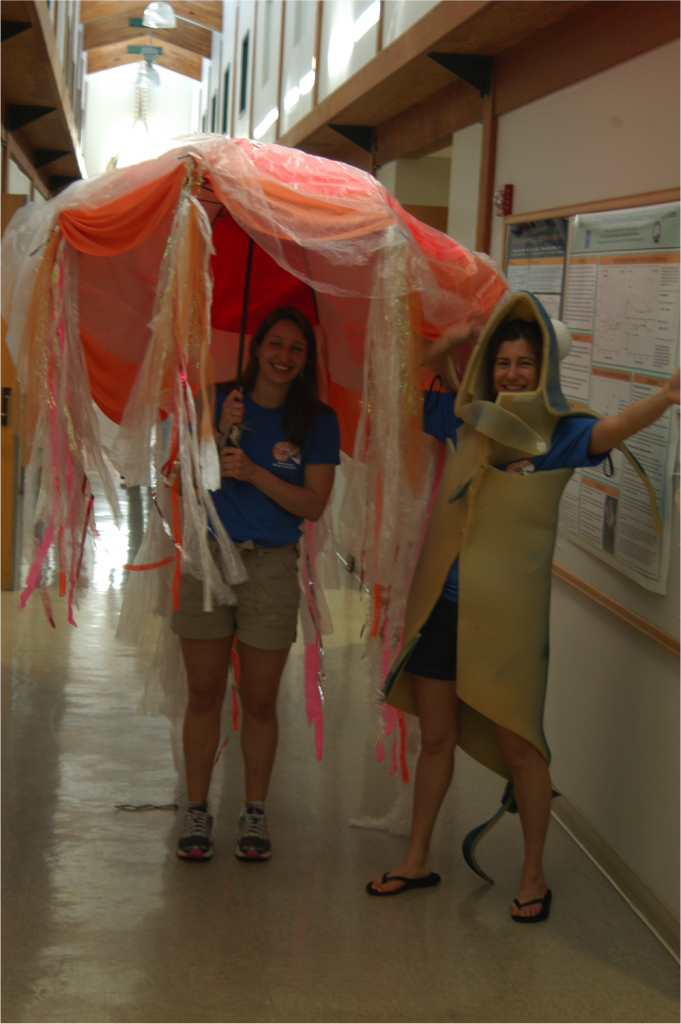

After weeks of preparation, our labor of love paid off when show time came. We’d parade down the halls during Open House with a giant jellyfish umbrella to round up an audience. Often we returned with a trail of young fans behind us—repeat attendees who just couldn’t get enough of our silly antics. The first show was never quite polished, as we still worked out the kinks, but it improved throughout the three shows we did each day—sometimes followed by an encore performance thanks to popular demand.

The greatest feeling was peeking out behind the curtain before a show and seeing it was standing room only. During the best performances, it was sheer electricity backstage. We fed off the energy of our young and enthusiastic audience members, usually sitting in the front row. We would mouth along to our favorite jokes and wait for the laughs that (usually) followed. While we pinned the script to the back of the curtain, we often managed to lose our places while reading lines, which earned a few extra laughs. And when the music started up, we’d rush out from behind the curtain to belt out our song-and-dance numbers. It doesn’t get much better than playing air guitar while singing about copepods.

While the shows were incredibly fun, they could also make a more lasting impression. I was stunned when a fellow student told me that after watching all of our performances, her daughter knew all the words to a song about rockfish taxonomy. It was called “Scorpaena guttata,” which is the scientific name of the California scorpion fish, set to the Lion King’s “Hakuna Matata” (I claim responsibility for the extreme fish nerdiness). Getting a three year old to sing about systematics without realizing it—I’d say that’s mission accomplished.

And then, of course, there was the “after hours puppet show,” the adults-only performance that was largely an incentive to get everyone to stick around and clean up on Sunday evening when Open House was through. Sometimes by request we’d first perform the regular puppet show for all the folks who were too busy working their shifts to catch it during Open House. Then we’d frantically tape the faces of unsuspecting audience members onto the puppets during a quick change, and commence with a “not safe for work” version of the show filled with dirty jokes and jabs at various students, faculty, and staff—or sometimes a completely new and barely intelligible creation. With beers in hand, I think our audience wasn’t too bothered by whether the storyline made any sense. It was a fitting way to cap off a weekend of incredible hard work and intense public outreach.

Technical difficulties often managed to thwart our best intentions to record the puppet show (the regular show, that is – strict rules against filming the after-hours show!). We did succeed one year (see this ). But I have to say the real magic comes in seeing (and performing) a show live. The shows will definitely live on fondly in my memory—and hopefully in those of some young audience members turned marine scientists.

Here is a link to a video of the 2013 MLML Puppet Show on the deep sea: http://islandora.mlml.calstate.edu/islandora/object/islandora%3A1710