By Jim Harvey (15 June 2017)

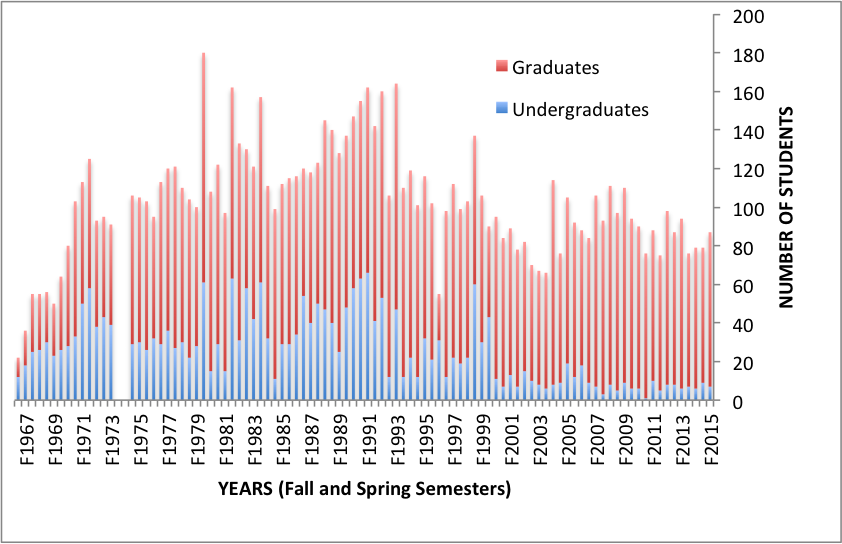

As I have mentioned before in a previous post, we have secured some funding and procured the services of Nora Deans and Eric Cline to help produce a celebratory and historical book about the first 50 years of MLML.

Here are some mock ups of various aspects of the document so you can get a feel for what we are trying to produce.

Possible Front Cover:

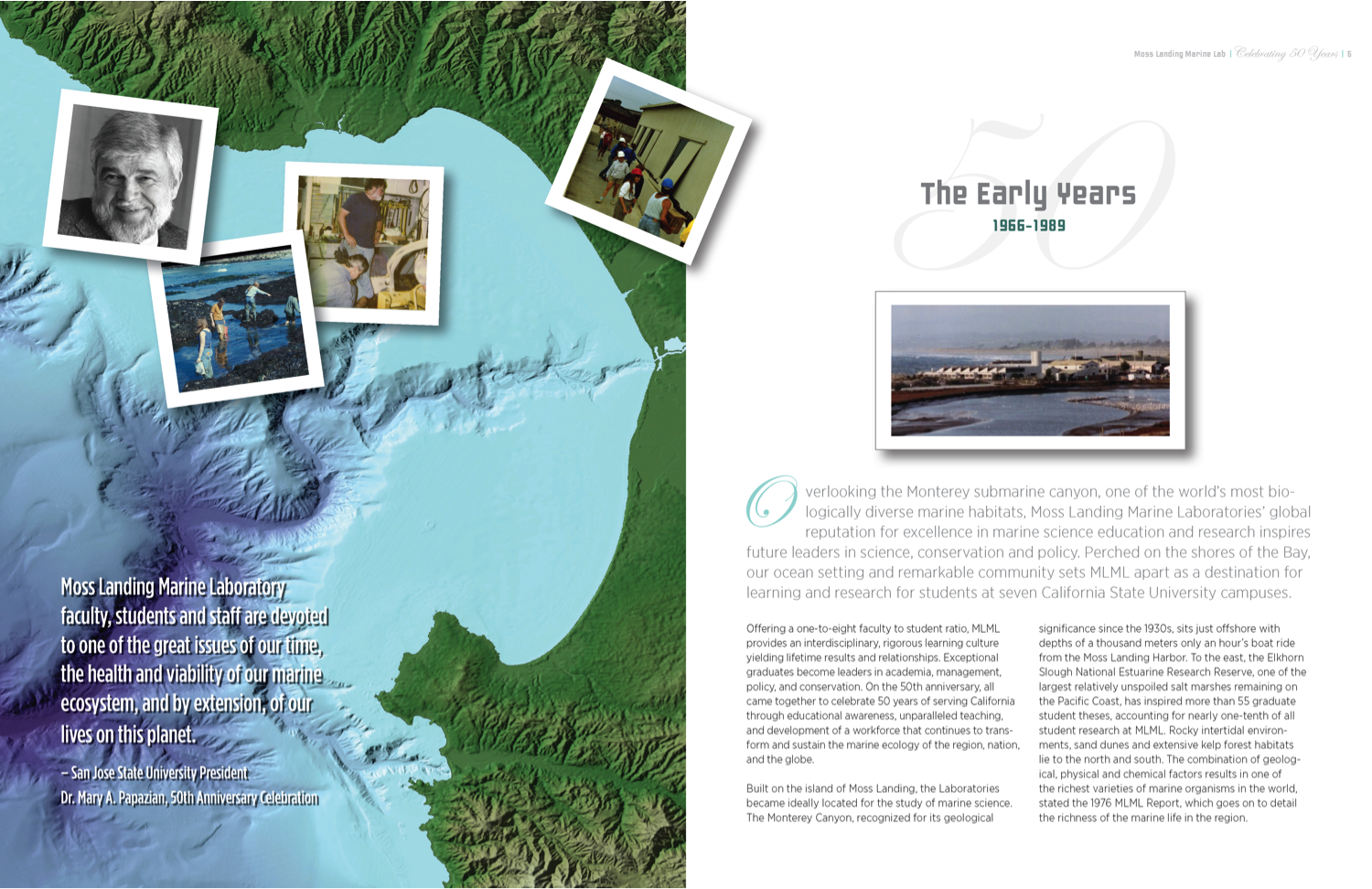

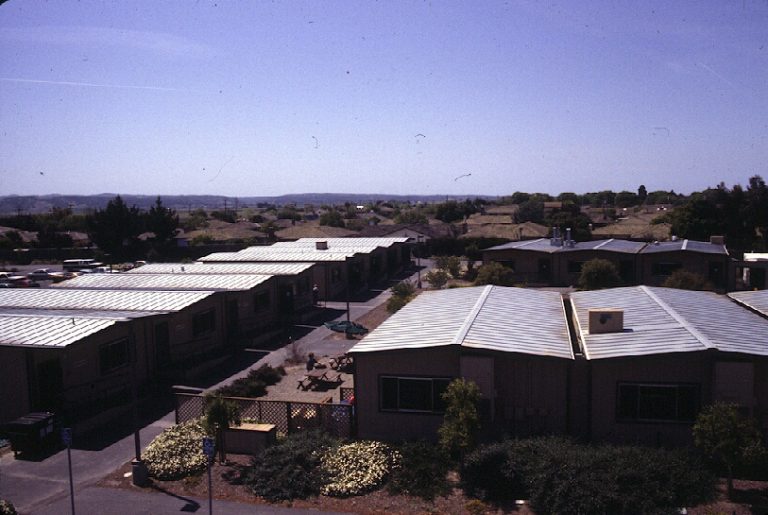

Example of two pages about the Early Years and Open House:

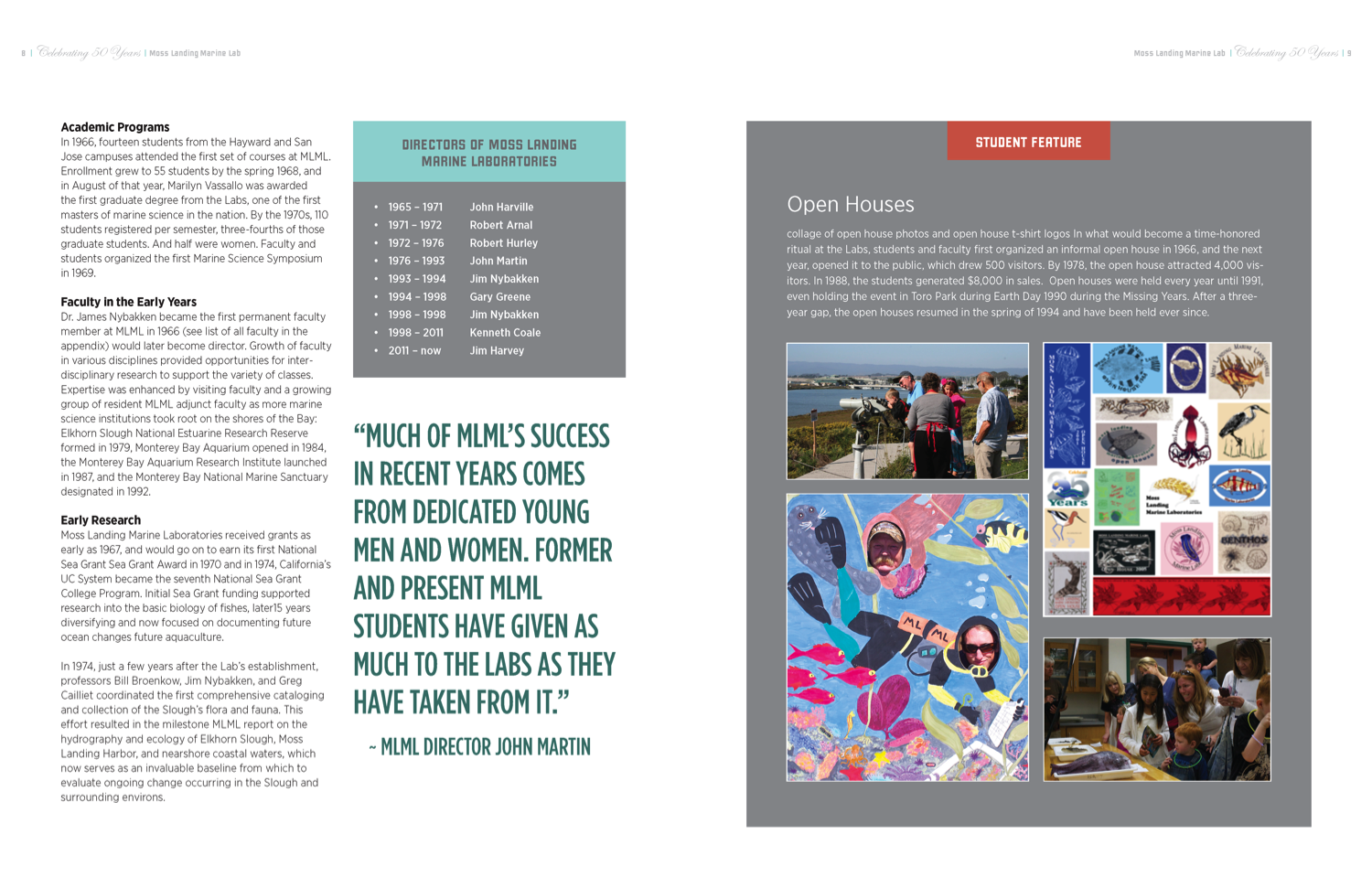

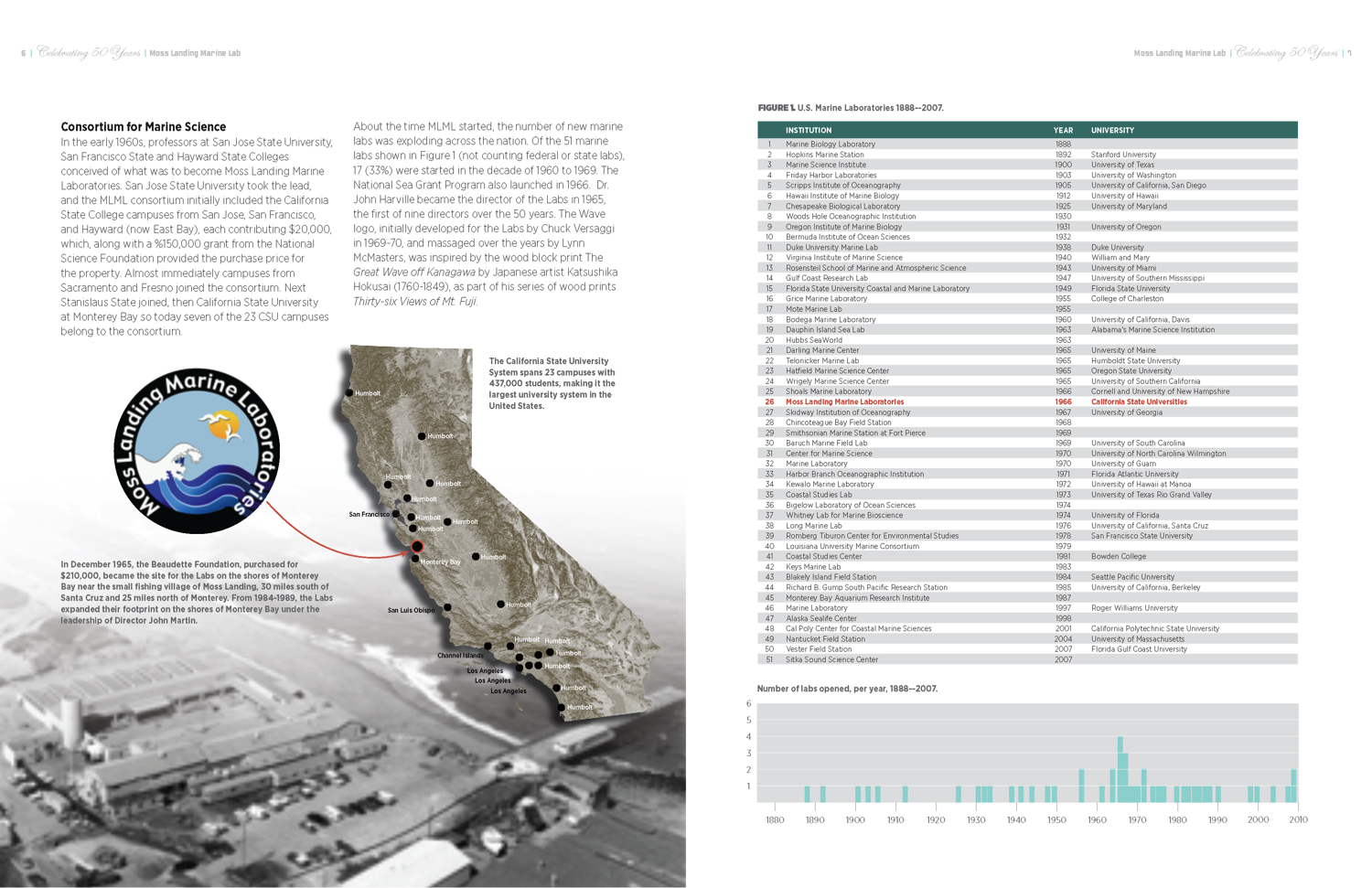

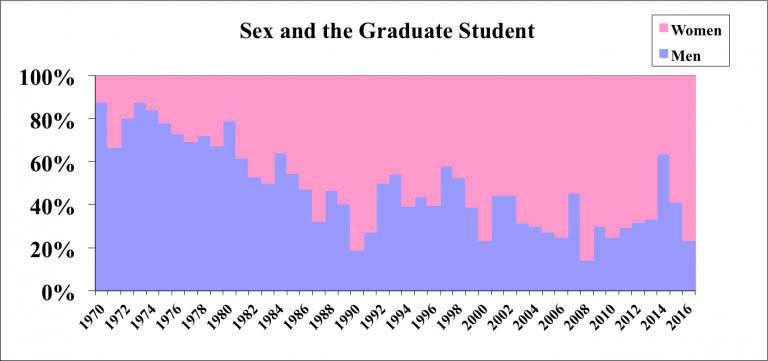

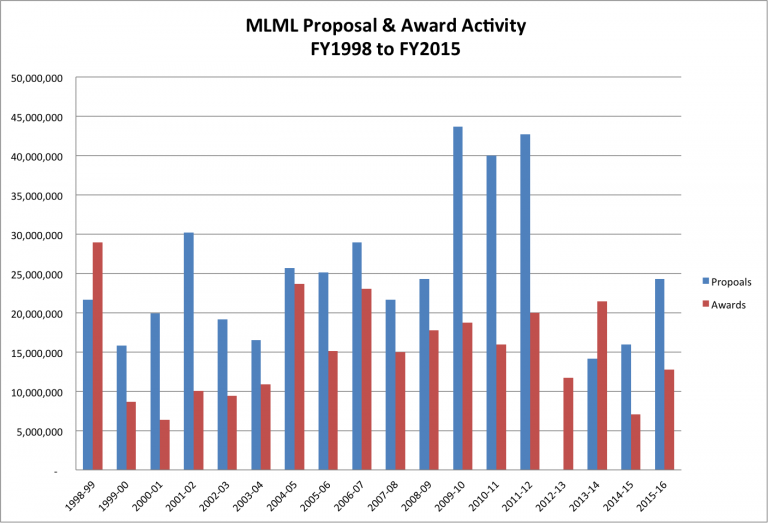

About the MLML Consortium:

We are well along in producing the book but one of the reasons for writing this post is that we need your help. We want to publish the names of all the students that have received their M.S. degrees from MLML, with the year and advisor. But our list is not complete, especially as it relates to the advisor. So can you please take a look at the list below and check your (and others you know) information to see if it is correct, and see if you can provide us needed information in the highlighted areas. Send an email back to us with the correct data. Thanks for your help.

Our current list of MLML M.S. graduates, in alphabetical order. Please check to see if your and others information is correct. Needed data have a question mark and are in red. Email me back with corrections: harvey@mlml.calstate.edu. Gracias.

| Last Name | First Name | MLML Graduation Year | Advisor or Lab |

| Ackerman | Lester | 1971 | Brittan |

| Adams | Joshua | 2004 | Harvey |

| Agegian | Catherine | 1981 | Hurley |

| Ainsley | Shaara | 2009 | Ebert/Cailliet |

| Ajeska | Richard | 1971 | Nybakken |

| Al-Ameri | Lubna | 2007 | Greene |

| Alicea | Antonio Jose | 2001 | Harvey |

| Alifano | Aurora | 2008 | Graham |

| Allen | Jane K. | 1992 | Nybakken |

| Ambrose | David | 1977 | Cailliet |

| Anderlini | Victor | 1972 | Martin? |

| Anderson | Brian | 1987 | Foster |

|

Anderson Anderson |

Todd W. Genevieve (Genny) |

1983 1971 |

Cailliet Nybakken |

| Anderson | Karen L. | 1979 | Cailliet |

| Anderson | M. Eric | 1977 | Cailliet |

| Andrews | Allen Hia | 1997 | Cailliet |

| Annett | Cynthia | 1982 | Nybakken |

| Antonio | Dean F. | 1994 | Foster |

| Antrim | Brooke | 1982 | Cailliet |

| Appiah | James | 1977 | Cailliet |

| Ardizzone | Daniele | 2005 | Cailliet |

| Armstrong | Edward M. | 1996 | Broenkow |

| B. Kauffman | William | 2009 | Coale |

| Baduini | Cheryl L. | 1995 | Harvey |

| Balance | Lisa | 1987 | Wursig? |

| Baltan | Jessica Jill | 2001 | Welschmeyer |

| Baltz | Donald | 1975 | Morejohn |

| Barminski | Robert | 1993 | Broenkow |

| Barnes | Cheryl | 2015 | Harvey |

| Barnett | Lewis | 2008 | Ebert/Cailliet |

| Barry | James | 1982 | Cailliet |

| Battle | Karen E. | 1994 | Nybakken |

| Beatman | Luke | 2006 | McPhee-Shaw |

| Bennett | Tony | 1993 | Cailliet |

| Benson | Scott R. | 2002 | Harvey |

| Benz | Sandy | 1973 | ? |

| Berger | Robert | 1983 | Cailliet |

| Bigman | Jennifer | 2013 | Ebert/Harvey |

| Bitondo | Alicia | 2016 | Geller |

| Bizzaro | Joe | 2005 | Cailliet |

| Black | Nancy A. | 1995 | Harvey |

| Blaskovich | David | 1973 | Broenkow |

| Blueford | Joyce | 1975 | ? |

| Bobco | Nicole | 2014 | Welschmeyer |

| Bockus | Daniel W. | 1999 | Foster |

| Bodensteiner | Laura | 2006 | Coale |

| Booth | Ashely | 2011 | McPhee-Shaw |

| Bork | Ken | 1986 | Ledbetter |

| Boyd | Jenny | 1992 | Harvey |

| Boyer | Shelby | 2010 | Geller |

| Boyle | Mariah | 2010 | Ebert/Cailliet |

| Braby | Caren E. | 1998 | Nybakken |

| Brady | Briana | 2008 | Cailliet |

| Breda | Valerie | 1982 | Foster |

| Breffit | Yvonne | 1976 | ? |

| Brennan | James | 1988 | Cailliet |

| Bretz | Carolyn (Carrie) | 1995 | Oliver/Foster |

| Brewster | Jodi | 2005 | Broenkow |

| Briggs | Kenneth | 1972 | Morejohn |

| Brookens | Tiffini | 2006 | Harvey |

| Brooks | Cassandra | 2008 | Cailliet |

| Brooks | Louise | 2005 | Harvey |

| Broughton | Jennifer | 2010 | Welschmeyer |

| Brower | Jeremiah | 2010 | Aiello |

| Brown | Simon | 2010 | Ebert/Cailliet |

| Brown | Elizabeth A. | 1996 | Harvey |

| Brown | Cynthia | 1990 | ? |

| Browne | Linda | 1997 | Cailliet |

| Browne | Patience | 1995 | Harvey |

| Bryant | Jeff | 1978 | Cailliet |

| Buchanan | Scott | 1990 | Wursig |

| Buckley | Shandy | 2012 | McPhee-Shaw |

| Burd | Matthew A. | 1992 | Harvey |

| Burdett | Kim | 1992 | Foster |

| Burger-Fadely | Janey | 1990 | Harvey |

| Burnett | Nancy | 1972 | Beeman |

| Burrows | Julia | 2009 | Harvey |

| Burton | Erica | 1999 | Cailliet |

| Byington | Amy | 2007 | Coale |

| Byrnes | Pamela E. | 1997 | Harvey |

| Caldwell | Suzanne | 1975 | ? |

| Camilli | Luis | 2007 | Greene |

| Canestro | Don | 1986 | Foster |

| Carle | Ryan | 2014 | Harvey |

| Carlisle | Aaron | 2006 | Cailliet |

| Carr | Mark | 1984 | Cailliet |

| Carroll | Dustin | 2009 | McPhee-Shaw |

| Caskey | Phillip | 1976 | Martin |

| Casson | Kathy | 1980 | Martin |

| Cates | Faye | 1976 | ? |

| Cazenave | Francois | 2008 | McPhee-Shaw |

| Cerchio | Salvatore | 1993 | Harvey |

| Chapin | Thomas | 1990 | Johnson |

| Chapman | John | 1974 | ? |

| Chappell | Paul | 1974 | ? |

| Chartock | Michael | 1969 | Nybakken |

| Cheney | Lisa C. | 1995 | Harvey |

| Chevalier | William J. | 2001 | Welschmeyer |

| Chin | Carol | 1991 | Johnson |

| Chinburg | Susan | 1980 | Arnal |

| Christensen | Robert | 1976 | ? |

| Christian | Vince | 2006 | Foster |

| Cintra-Buenrostro | Carlos | 2000 | Foster |

| Cipriano | Frank | 1983 | Martin |

| Clark | Casey | 2013 | Harvey |

| Clark | Ross P. | 1995 | Foster |

| Clark | Lee R. | 1972 | Broenkow |

| Clark | Patrick | 1972 | Nybakken |

| Clune | William | 1974 | ? |

| Cohen | Joel | 1972 | Moyle |

| Colbert | Debbie L. | 1999 | Johnson |

| Coley | Teresa L. | 1996 | Johnson |

| Collins | Clint | 2015 | Kim/Aiello |

| Connors | Eileen (Sarah ) M. | 2003 | Harvey |

| Conroy | Patrick T. | 1993 | Nybakken |

| Cook | William | 1974 | ? |

| Cooper | John | 1979 | Nybakken |

| Cope | Jason M. | 2002 | Cailliet |

| Cordes | Erik E. | 1999 | Nybakken |

| Cory | Carter | 1976 | ? |

| Courtney | Katherine | 1980 | Ann Hurley |

| Cowen | Robert | 1979 | Cailliet |

| Craig | Susan | 1997 | Nybakken |

| Crane | Nicole L. | 1992 | Harvey |

| Cresswell | Frances | 1985 | Wursig |

| Croll | Donald | 1986 | Wursig |

| Crow | Karen | 1995 | Larson |

| Cruickshank | Marilyn | 2015 | Harvey |

| Culley | Alex I. | 2000 | Welschmeyer |

| Curland | James M. | 1997 | Harvey |

| Curry | Barbara E. | 1990 | Harvey |

| Daly | Brendan J. | 1997 | Cailliet |

| Davis | Chanté | 2006 | Ebert/Cailliet |

| Davis | Paul | 1974 | Foster |

| Davis | William | 1972 | ? |

| Dawson | Cyndi | 2007 | Cailliet |

| de Marignac | Jean | 2000 | Cailliet |

| Dearn | Susan | 1987 | Foster |

| DeBie | Mark S. | 1991 | ? |

| DeVogelare | Andrew | 1986 | Foster |

| Dierks | Ann J. | 1990 | Wursig |

| Dittmer | Eric | 1972 | Arnal |

| Dominik | Clare | 2004 | Foster |

| Donham | Emily | 2016 | Hamilton |

| Donnellan | Michael | 2004 | Foster |

| Donnelly | Erica | 2012 | Harvey |

| Dorfman | Eric J. | 1990 | Harvey |

| Dorrell-Canepa | Joan M. | 1994 | Foster |

| Douglas | Barbara (Tess) | 2013 | Ferry/Cailliet |

| Downing | James W. | 1995 | Foster |

| Drake | Catherine | 2016 | Geller |

| Drake | Michelle | 2013 | Aiello |

| Dreyer | Jennifer | 2011 | Aiello |

| Duryea | Jahnava | 2014 | Cailliet |

| Dykzeul | James | 1976 | ? |

| Eastman | Sally | 1985 | Knauer |

| Eastman | James | 1975 | Nybakken |

| Ebert | Tom | 1988 | Nybakken |

| Ebert | Thomas | 1986 | Nybakken |

| Ebert | David A. | 1984 | Cailliet |

| Eckhardt | Terry | 1975 | Broenkow |

| Edmunds | Jody L. | 2000 | Welschmeyer |

| Edwards | Mathew S. | 1996 | Foster |

| Eguchi | Tomoharu | 1998 | Harvey |

| Eimoto | Dennis | 1976 | ? |

| Eissinger | Richard | 1971 | ? |

| Eliason | Donald | 1985 | Broenkow |

| Elrod | Virginia | 1987 | Johnson |

| Endris | Charles | 2009 | Aiello |

| Engel | Jonna D. | 1997 | Nybakken |

| Erdey | Mercedes | 2007 | Greene |

| Estelle | Veronica B. | 1991 | Harvey |

| Evans | Ronald | 1976 | Lyke |

| Ezcurra | Juan M. | 2001 | Cailliet |

| Fairey | William Russell | 1992 | Johnson |

| Farrens | Gary | 1971 | Silver |

| Farris | Monica | 1977 | Niesen |

| Faurot | Ellen | 1990 | Wursig |

| Feinholtz | Daniela Maldini | 1996 | Harvey |

| Feinholz | Michael E. | 1996 | Broenkow |

| Fellows | Deborah L. | 1980 | Knauer |

| Fennie | Hamilton "Will" | 2015 | Hamilton |

| Ferioli | Laurie J. | 1997 | Johnson |

| Ferry | Lara A. | 1994 | Cailliet |

| Field | Jeff | 2007 | Cailliet |

| Fields | Ryan | 2016 | Hamilton |

| Fields | Doug | 1982 | Cailliet |

| Fisher | Jennifer | 2005 | Kim/Geller |

| Fitzgerald | Laurie | 2003 | Geller |

| Fitzwater | Steve | 1984 | Martin |

| Flammang | Brook | 2005 | Ebert/Cailliet |

| Flegal | Arthur | 1976 | Martin |

| Flora | Stephanie J. | 2001 | Broenkow |

| Forrest | Matthew J. | 2004 | Foster |

| Fox | Michael | 2013 | Graham |

| Frantz | Brian R. | 1999 | Coale |

| Frechette | Danielle | 2010 | Harvey |

| Friend | Theresa | 2003 | Harvey |

| Fry | Jasmine | 2009 | Ebert/Cailliet |

| Fukuyama | Allan | 1985 | Nybakken |

| Fulton-Bennett | Heather | 2016 | Graham |

| Fusaro | Craig | 1969 | Nybakken? |

| Gabara | Scott | 2014 | Graham |

| Gagneron | (Lam) Elizabeth | 2016 | Welschmeyer |

| Gammell | Barry | 1975 | ? |

| Gardner-Taggart | Joan M. | 1991 | Ledbetter |

| Garrick | Huey | 1974 | ? |

| Garrison | David | 1972 | Silver (+ Broenkow) |

| Gashler | Joseph A. | 1996 | Broenkow |

| Gehringer | Daphne | 2007 | Geller |

| Gibble | Corinne | 2011 | Harvey |

| Gibbs | Melissa A. | 1991 | Cailliet |

| Glenn | Kyle | 2009 | Graham |

| Glickstein | Neil | 1977 | Martin |

| Goldberg | Judah | 2003 | Welschmeyer |

| Goldberg | Nisse A. | 2001 | Foster |

| Golson | Emily | 2014 | Harvey |

| Goodyear | Jeff | 1989 | Wursig |

| Gordon | Michael | 1976 | Martin |

| Graham | Tanya | 2009 | Harvey |

| Graham | Michael H. | 1995 | Foster |

| Grannis | Edward | 2006 | Cailliet |

| Grant | Nora | 2009 | Ferry/Graham |

| Grebel | Joanna | 2003 | Cailliet |

| Green | Kristen | 2010 | Cailliet |

| Green | Bonnie | 1978 | Morejohn |

| Greenberg | Nina | 1992 | Nybakken |

| Greene | Nancy | 1982 | Broenkow |

| Greene | Gary | 1970 | Arnal |

| Greenier | Jennifer L. | 1991 | Nybakken |

| Greenley | Ashley | 2009 | Cailliet |

| Greig | Denise J. | 2002 | Harvey |

| Grimm | Brigit | 1989 | Wursig |

| Guenther | Elizabeth A. | 1999 | Johnson |

| Guerrero | Jo | 1989 | Wursig |

| Haas | Diane | 2011 | Ebert/Cailliet |

| Hall | Laurie | 2008 | Harvey |

| Hamilton | Sonia Linnick | 1984 | Nybakken |

| Hanna | Beverly M. | 1991 | Cailliet |

| Hannan (Zimmer) | Cheryl | 1980 | Nybakken |

| Hansen | Judy | 1972 | Silver |

| Hansen | John | 1972 | Tribbey |

| Harvey | Thomas | 1981 | Morejohn |

| Harvey | James Thomas | 1978 | Morejohn |

| Haskins | John C. | 2002 | Coale |

| Hata | Aric | 1976 | ? |

| Hauschildt | Kathy | 1985 | Broenkow |

| Hawes | Sandra | 1983 | Cailliet |

| Hawk | Heather | 2010 | Geller |

| Hawkinson | Craig A. | 1992 | Harvey |

| Head | William | 1974 | Martin |

| Heard | Andrew J. | 1992 | Broenkow |

| Heard | Janet | 1992 | Oberdorfer |

| Heath | Kathryn | 1988 | Mullins |

| Hebel | Dale | 1983 | Knauer |

| Heilprin | Daniel J. | 1992 | Cailliet |

| Heim | Wesley | 2003 | Coale |

| Heimlich-Boran (Boran) | James | 1988 | Wursig |

| Heimlich-Boran (Heimlich) | Sara | 1988 | Wursig |

| Heine | John | 1982 | Foster |

| Helm | Roger | 1979 | Morejohn |

| Henkel | Laird | 2003 | Harvey |

| Hennessy | Scott | 1972 | Morejohn? |

| Herbert | Alan | 1986 | ? |

| Hernandez | Keith | 2016 | Harvey |

| Herrlinger | Tim | 1983 | Nybakken |

| Hester | Michelle | 1997 | Harvey |

| Hilaski | Roger | 1972 | Moyle |

| Hill | Kevin | 1986 | Cailliet |

| Hoelzer | Guy A. | 1982 | Cailliet |

| Holte | Jane E. | 1994 | Foster |

| Honma | Lawrence O. | 1994 | Foster |

| Hoos | Phillip | 2007 | Geller |

| Hooton-Kaufman | Brynn | 2012 | Graham |

| Hoover | Brian | 2013 | Harvey |

| Hornberger | Michelle I. | 1991 | Ledbetter |

| Houk | James | 1970 | Harmon |

| Howard | Alexis | 2014 | Graham |

| Hsieh | Chih-Lin | 1982 | Cailliet |

| Hsueh | Pan Wen | 1989 | Nybakken |

| Huber | Matthew | 2009 | Welschmeyer |

| Hughes | Stephanie | 2012 | Harvey |

| Hughes | Brent | 2007 | Graham |

| Hughes | Bill | 1987 | Shiller |

| Hulberg | Larry | 1978 | Nybakken |

| Hulme | Samuel | 2005 | Greene |

| Hunt | John | 1987 | Nybakken |

| Hunt | Douglas | 1976 | Beeman |

| Hunter | Craig | 1976 | Martin |

| Hunter-Thomson | Kristin | 2011 | Cailliet |

| Hutto | Sara | 2011 | Graham |

| Hymanson | Zachary | 1986 | Foster |

| Iampietro | Pat J. | 1999 | Nybakken/Foster |

| Jacobi | Michele | 1999 | Nybakken |

| Bradford | Donna | 1987 | Cailliet |

| James | Kelsey | 2011 | Ebert/Cailliet |

| James | Dave W. | 1998 | Foster |

| Jefferson | Thomas A. | 1989 | Wursig |

| Jeffries | Sarah | 2015 | Graham |

| Jensen | Erin | 2010 | Geller |

| Johnsen | Jeffrey | 2013 | Welschmeyer |

| Johnson | Shannon | 2003 | Geller |

| Johnson (Schaeffer) | Korie Ann | 1997 | Cailliet |

| Johnson | Eric W. | 1984 | Cailliet |

| Jones | Nathan | 2013 | Harvey |

| Jones | Erin | 2000 | Cailliet |

| Jones | Mary Lou | 1985 | Leadbetter? |

| Jorve | Jennifer | 2008 | Graham |

| Jungmann | Thomas | 1982 | Hassur |

| Kahn | Amanda | 2010 | Geller |

| Kao | Jon S. | 2000 | Cailliet |

| Kaplan | Kristen Brynie | 2000 | Nybakken |

| Karpov | Konstantin | 1977 | Cailliet |

| Kashef | Neosha | 2012 | Cailliet |

| Kashiwada | Jerry | 1981 | Cailliet |

| Kay | Rachel | 2001 | Broenkow |

| Kay | Phillip A. | 1990 | ? |

| Keating | Kelene | 2013 | Welschmeyer |

| Keating | Tom | 1986 | Cailliet |

| Keiper | Carol | 2001 | Harvey |

| Kellogg | Michael | 1982 | Nybakken |

| Kemper | Jenny | 2012 | Ebert/Cailliet |

| Kenner | Michael | 1987 | Foster |

| Kerr | Lisa | 2002 | Cailliet |

| Keusink | Chris | 1979 | Cailliet |

| Kieckhefer | Thomas R. | 1992 | Harvey |

| Kiest | Kim A. | 1993 | Nybakken? |

| Kim | Yong Sung | 1996 | Broenkow |

| Kim | Stacy L. | 1989 | Oliver (Foster) |

| Kimball | Thomas | 2006 | Coale |

| Kimura | Scott | 1976 | Foster |

| King | Chad | 2003 | Geller |

| King | Aaron E. | 1993 | Cailliet |

| King | Jane | 1992 | Nybakken? |

| Kingsley | Eric S. | 1999 | Johnson |

| Kitaguchi | Briar | 2011 | Kim/Aiello |

| Kitazono | Elizabeth T. | 1978 | Broenkow |

| Klaus | Annaliese | 1987 | ? |

| Klaus | Adam | 1986 | Ledbetter |

| Kliever | Richard | 1976 | Cailliet |

| Kline | Donna E. | 1996 | Cailliet |

| Klosinski | Jarred | 2015 | Graham |

| Knesl | Zoe | 2002 | Foster |

| Knowles | Thomas | 2012 | Geller |

| Kohtio | Diana | 2007 | Graham |

| Konar | Brenda J. | 1991 | Foster |

| Krasnow | Lynne | 1978 | Morejohn |

| Kuhnz | Linda | 2000 | Harvey |

| Kukowski | Gary | 1972 | Morejohn |

| Kumar | Anurag | 2003 | Harvey |

| Kuo | Julie | 2015 | Welschmeyer |

| Kusher | David | 1986 | Cailliet |

| Kvitek | Rikk | 1986 | Nybakken |

| Ladizinsky | Nicolas C. | 2003 | Coale |

| Laman | Edward A. | 1998 | Cailliet |

| Lamerdin | Stewart | 2000 | Welschmeyer |

| Lamont | Margaret | 1995 | Harvey |

| Lander | Michelle E. | 1998 | Harvey |

| Landrau | Maria E. | 2000 | Welschmeyer |

| Lasley | Stephen | 1977 | Broenkow |

| Launer | Andrea | 2014 | Harvey |

| Laurent | Laurence | 1971 | Nybakken |

| Lawson | Vera | 2016 | Aiello |

| Leaf | Rob | 2005 | Cailliet |

| Lefebvre | Kathi A. | 1995 | Nybakken |

| Lenihan | Hunter | 1993 | Johnson |

| Leonard | George H. | 1993 | Foster |

| Leopold | William R. | 2000 | Cailliet |

| Leopold | Lawrence | 1972 | ? |

| Levey | Matthew D. | 2005 | Cailliet |

| Levitt | Jennifer L. | 1990 | Niesen |

| Levitt | Jon | 1989 | Arp |

| Lewis | Roger C. | 2002 | Coale |

| Lewis | Lynn M. | 1992 | Nybakken |

| Lewitus | Alan | 1984 | Broenkow |

| Lindquist | David | 1999 | Cailliet |

| Lindquist | David | 1971 | Nybakken |

| Lindsey | Jacqueline (Schwarstein) | 2016 | Harvey |

| Locke | James | 1971 | Arnal |

| Locy | Steven | 1980 | Nybakken |

| Loeb | Valerie | 1972 | Morejohn |

| Lohr | Heather | 2003 | Geller |

| Loiacono | Stephen | 2016 | Geller |

| Lontoh | Deasy | 2014 | Harvey |

| Lopez | Holly | 2007 | Greene |

| Lorne | Michael | 1978 | Martin |

| Loung | Eileen | 1975 | ? |

| Loury | Erin | 2011 | Ebert/Cailliet |

| Lovera | Christopher F. | 2001 | Welschmeyer |

| Lowe | Patricia B. | 1999 | Foster |

| Lundsten | Lonny | 2007 | Geller |

| Mahoney | Melissa | 2002 | Cailliet |

| Manugian | Suzanne | 2013 | Harvey |

| Mariant | Judy J. | 1993 | Ledbetter |

| Marrack | Elizabeth Case | 1997 | Foster |

| Marraffini | Michelle | 2013 | Geller |

| Martin | Linda K. | 1982 | Cailliet |

| Mason | John W. | 1997 | Harvey |

| Matthews | Kathleen | 1983 | Cailliet |

| Maurer | Brian | 2013 | Welschmeyer |

| Mauri | Elena | 2000 | Welschmeyer |

| Mayer | Melanie | 1987 | Foster |

| Mayes | Timothy | 1975 | ? |

| McAfee | Skyli | 1994 | Cailliet |

| McBride | Susan C. | 1990 | Nybakken |

| McConnico | Laurie | 2003 | Foster |

| McCormick | Susan | 1983 | Nybakken |

| McDonald | Gary | 1976 | Nybakken |

| McHuron | Elizabeth | 2012 | Harvey |

| McInnis | Rodney | 1976 | Broenkow |

| McKell | Erinn | 2010 | Welschmeyer |

| McKibbin | Robert | 1975 | ? |

| McMillan | Selena | 2010 | Graham |

| McMillan | Patricia A. | 2003 | Kim/Welschmeyer |

| McNulty | Hilary R. | 1992 | Cailliet |

| Melwani | Aroon | 2004 | Kim/Welschmeyer |

| Mesick | Robert | 1975 | ? |

| Meyer | Robert | 1974 | ? |

| Miller | William | 1975 | ? |

| Mitts | Patrick | 2003 | Greene |

| Moran | Clinton | 2011 | Ferry/Cailliet |

| Moran | Mike | 1976 | Tullis |

| Moreno | Guillermo | 1990 | Cailliet |

| Morrice | Katherine | 2011 | McPhee-Shaw |

| Moser | Doreen | 1996 | Harvey |

| Muhs | Katherine S. | 1998 | Nybakken |

| Muller | Jeff | 1987 | Leadbetter |

| Munroe | Jean | 1969 | ? |

| Murai | Lee | 2007 | Greene |

| Muth | Arley | 2010 | Graham |

| Myers | Allison | 2006 | Coale |

| Nagel | David | 1983 | Mullins |

| Nakagawa | Melinda | 2014 | Harvey |

| Narine | Vidya | 1976 | Baad |

| Natanson | Lisa | 1984 | Cailliet |

| Navas | Gabriela | 2015 | Hamilton |

| Nebenzahl | Debborah A. | 1997 | Cailliet |

| Neer | Julie A. | 1998 | Cailliet |

| Negrey | John | 2013 | Coale |

| Neustrup | Neils | 1976 | ? |

| Nevins | Hannah | 2004 | Harvey |

| Nichols | Stephanie | 2001 | Cailliet |

| Nicholson | Teri E. | 2000 | Harvey |

| Nigg | Eric | 1988 | Foster |

| Nishimoto | Mary M. | 1996 | Cailliet |

| Niven | Eric | 2013 | Aiello |

| Nolten | Jeffery | 1980 | Broenkow |

| Norris | Tenaya | 2013 | Harvey |

| Norris | Thomas F. | 1995 | Harvey |

| Norris | James | 1970 | Bell |

| Novak | Tanya | 2011 | McPhee-Shaw |

| Nowicki | Jocelyn L. | 1992 | Johnson |

| Oakden | James | 1981 | Nybakken |

| Oates | Stori C. | 2005 | Harvey |

| Byrd (Odom) | Barbie | 2001 | Harvey |

| Oeker (Anderson) | Genevieve | 1971 | Nybakken |

| Ohman | Mark | 1976 | Martin |

| O'Kane | John | 1970 | Arnal |

| Okey | Thomas | 1993 | Oliver/Nybakken |

| Oliver | John | 1973 | Nybakken |

| Orr | Anthony J. | 1998 | Harvey |

| Osborn | Steven A. | 1995 | Nybakken |

| Osnes-Erie | Lizabeth D. | 1999 | Harvey |

| Ouellette | Thomas | 1978 | Martin |

| Outram | Dawn | 2000 | Cailliet |

| Overstrom-Coleman | Max | 2009 | Graham |

| Oxman | Dion S. | 1995 | Harvey |

| Pace | Stephen | 1978 | Cailliet |

| Palacios | Sherry L. | 2003 | Foster |

| Palomino | Eufemia | 2002 | Broenkow |

| Parker | Karen | 2013 | Welschmeyer |

| Parker | Pamela | 2006 | Harvey |

| Parkin | Jennifer L. | 1998 | Harvey |

| Peglow | Justin | 2013 | Aiello |

| Perez | Colleena | 2005 | Ebert/Cailliet |

| Perlman | Benjamin | 2010 | Ferry/Cailliet |

| Peters | Darryl W. | 2002 | Broenkow |

| Phillips | Elizabeth M. | 2005 | Harvey |

| Phillips | Bryn M. | 1995 | Nybakken |

| Phillips | Charles | 1978 | Martin |

| Pranger | Mark L. | 1999 | Broenkow |

| Proulx | Steve | 1987 | Cailliet |

| Puglise | Kimberly A. | 2003 | Welschmeyer |

| Purdue | Andrea | 1976 | Martin |

| Quaranta | Kim | 2011 | Ferry/Cailliet |

| Raanan | Ben Yair | 2015 | McPhee-Shaw |

| Ramer | Bernadette | 1985 | Cailliet |

| Rasch | Richard | 1985 | Mullins |

| Rasmussen | Kristin | 2006 | Harvey |

| Raum-Suryan | Kimberly L. | 1995 | Harvey |

| Reaves | Richard | 1983 | Broenkow? |

| Reed | Daniel | 1981 | Foster |

| Reilly | Paul | 1978 | Broenkow |

| Reuter | Rebecca F. | 1999 | Cailliet |

| Reyes | Catalina | 2009 | Graham |

| Reynolds | Kyle | 2009 | Kim/Welschmeyer |

| Rhett | Gillian | 2014 | Harvey |

| Rhodes | Kevin | 1995 | Cailliet |

| Rinewalt | Christopher | 2007 | Ebert/Cailliet |

| Riosmena-Rodriguez | Rafael | 1997 | Foster |

| Roberts | Alice (Atma) | 2001 | Welschmeyer |

| Roberts | Cassandra A. | 1996 | Foster |

| Roberts | Dale | 1979 | Bradbury/Cailliet |

| Robinson | Kristin | 2015 | Geller |

| Robinson | Heather | 2006 | Ebert/Cailliet |

| Romero | Rosemary | 2009 | Graham |

| Rose | Dennis | 1980 | Foster |

| Ross | Bruce E. | 1977 | Arnal |

| Rote | James | 1969 | Martin |

| Ruagh | Amer Ali | 1976 | Cailliet |

| Ruvalcaba | Jasmine | 2014 | Graham |

| San Filippo | Rich A. | 1996 | Cailliet |

| Sanders | Rhea | 2007 | Coale |

| Sandoval | Eric J. | 2005 | Greene |

| Sankaran | Sonya | 2012 | Graham |

| Sassoubre | Lauren | 2008 | Coale |

| Schaadt | Timothy | 2005 | Graham |

| Schaaf | Jayna | 2007 | Ebert/Cailliet |

| Schaeffer | Timothy | 1999 | Foster |

| Schlining | Brian M. | 1999 | Broenkow |

| Schlining | Kyra L. | 1999 | Nybakken |

| Schmeltzer | Emily | 2016 | Hamilton |

| Schmidt | Katherine | 2014 | Cailliet |

| Schneider-Plechner | Barbara S. | 1996 | Foster |

| Schnitzler | Christie | 2005 | Geller |

| Schoenherr | Jill | 1987 | Wursig |

| Scholten | James Walter | 1999 | Harvey |

| Schrader | Carl | 1979 | Foster |

| Schultz | Paul | 1971 | ? |

| Schwartz | David | 1983 | Mullins |

| Scianni | Christopher | 2008 | Welschmeyer |

| Scudder | Barbara | 1984 | Knauer |

| Sekiguchi | Keiko | 1988 | Wursig |

| Shaffer | Jane L. | 1986 | Nybakken |

| Shea | Russell | 1980 | Broenkow |

| Shonman | David | 1976 | Nybakken |

| Shumaker | Evelyn | 1976 | Arnal |

| Silber | Greg | 1986 | Wursig |

| Silberstein | Mark | 1987 | Nybakken |

| Simmons | Keith | 1976 | ? |

| Singer | Michael | 1982 | Cailliet |

| Slattery | Marc Peter | 1986 | Nybakken |

| Slattery | Peter | 1980 | Nybakken? |

| Sliger | Mark | 1982 | Nybakken |

| Smethie | William M. Jr. | 1973 | Broenkow |

| Smith | Sarah | 2009 | Welschmeyer |

| Smith | Wade D. | 2005 | Cailliet |

| Smith | James G. | 2001 | Welschmeyer |

| Smith | Don | 1985 | Martin (and Knauer)? |

| Smith | Richard E. | 1974 | Broenkow |

| Smith-Beasley | Lisa | 1992 | Cailliet |

| Solonsky | Allan | 1983 | Cailliet |

| Sorenson | Fred | 1984 | Nybakken |

| Spalding | Heather L. | 2002 | Foster |

| Spear | Larry | 1987 | Morejohn |

| Stafford | David | 2012 | Cailliet |

| Starbird | Chris | 1993 | Harvey |

| Stein | Janet | 1989 | Wursig |

| Steller | Diana L. | 1993 | Foster |

| Stephenson | Mark | 1974 | Nybakken |

| Stevens | Pat | 1976 | ? |

| Stewart | Katherine | 1976 | Thompson |

| Strauss | William | 1975 | ? |

| Strobel | Burke | 1996 | Foster |

| Strong | Craig | 1990 | Harvey |

| Stuart | Laurie | 1980 | Morejohn |

| Sullivan | Deidre E. | 1994 | Greene |

| Sullivan | Laurie | 1994 | ? |

| Summers | Anne C. | 1993 | Nybakken |

| Suryan | Robert M. | 1995 | Harvey |

| Suskiewicz | Matthew | 2010 | Graham |

| Sweeney | Joelle | 2008 | Harvey |

| Swithenbank | Alan M. | 1991 | Broenkow |

| Szesciorka | Angela | 2015 | Harvey |

| Szoboszlai | Amber | 2007 | Graham |

| Talent | Larry | 1973 | Staebler |

| Tanadjaja | Elsie | 2010 | Aiello |

| Tanner | Melinda | 2016 | Aiello |

| Tarpley | John A. | 1992 | Foster |

| Teas | Howard | 1982 | Broenkow |

| Tershey | Bernie R. | 1993 | Harvey |

| Thomas | Kate | 2008 | Harvey |

| Thompson | Joel | 1983 | Mullins? |

| Thompson | Janet | 1975 | ? |

| Thurber | Andrew | 2005 | Kim/Welschmeyer |

| Tilden | Janet E. | 2005 | Greene |

| Toimil | Lawrence | 1975 | ? |

| Tompkins | Paul | 2011 | Graham |

| Tomson | Janice | 1985 | Ledbetter |

| Toperoff | Amanda K. | 2002 | Harvey |

| Torok | Michael L. | 1994 | Harvey |

| Trejo | Tonatiuh | 2005 | Cailliet |

| Trone | John W. | 1994 | Foster |

| Trumble | Stephen J. | 1995 | Harvey |

| Turnau | Rene | 1987 | Ledbetter |

| Turner | Teresa | 1977 | Nybakken |

| Urrere | Madelain | 1982 | Knauer |

| Uttal | Lisa | 1992 | Nybakken |

| Van Buren | Marik | 1980 | ? |

| Van Dykhuizen | Gilbert | 1983 | Cailliet |

| Van Kelley (Andrews) | Hees | 2014 | Ebert/Hamilton |

| Vanderwilt | Deborah | 1983 | Nybakken |

| Varoujean | Daniel | 1972 | Moyle |

| Vassallo | Marilyn | 1968 | Nybakken |

| Vaughan | Doug | 1978 | Cailliet |

| Vega | Gabriela | 2008 | Kim/Welschmeyer |

| Ventresca | David | 1975 | Morejohn? |

| Vercoutere | Tom | 1982 | ? |

| Versaggi | Charles | 1975 | Morejohn? |

| Volpi | Christina | 2014 | McPhee-Shaw |

| von Langen | Peter | 1996 | Johnson |

| Von Thun | Susan | 2001 | Geller |

| Voss | Tamara | 2002 | Kim/Coale |

| Wade | Pamela Neeb | 2016 | Geller |

| Wadsworth | Thomas | 2009 | Cailliet |

| Wagner | Gala | 2006 | Welschmeyer |

| Wagner | Amy L. | 1994 | Nybakken |

| Waidlich | Russell | 1976 | Broenkow? |

| Wakeham | Bruce | 1974 | ? |

| Walder | Ronald K. | 1999 | Foster |

| Walker | Christine A. | 1998 | Harvey |

| Wallace | Farron | 1986 | Cailliet |

| Walsh | Jonathan | 2011 | Cailliet |

| Waterhouse | Tye Y. | 1992 | Welschmeyer |

| Watson | Daniel | 1976 | Foster |

| Watt | Steven G. | 2003 | Greene |

| Watters | Diana L. | 1993 | Cailliet |

| Watts | Bridget | 2006 | Harvey |

| Webb Wertz | Lisa | 2013 | Harvey |

| Weesner | Michael | 1970 | ? |

| Wehrenberg | Megan | 2009 | Graham |

| Weise | Michael J. | 2000 | Harvey |

| Welden | Bruce A. | 1985 | Cailliet |

| Wheeler | Ashley | 2015 | Aiello |

| White | Michelle D. | 1998 | Nybakken |

| Wieters | Evie A. | 2000 | Foster |

| Wilkin | Sarah M. | 2003 | Harvey |

| Willard | James | 1981 | Lyke |

| Williams | Kristine | 2013 | Harvey |

| Wilson | Carrie Melissa | 2001 | Foster |

| Winton | Megan | 2011 | Ebert/Cailliet |

| Wittlinger | Sara | 2002 | Foster |

| Wold | Lucy | 1991 | Cailliet |

| Wolf | Stephen | 1968 | Arnal |

| Wong | Cary R. | 1989 | Broenkow |

| Woods | April | 2016 | Welschmeyer |

| Woolfolk | Andrea M. | 1999 | Foster |

| Worden | Sara | 2015 | Graham |

| Wright | William | 1979 | Nybakken? |

| Wyatt | Deborah | 1993 | Cailliet |

| Wyse | Diane | 2014 | McPhee-Shaw |

| Yamada | Randy | 1979 | ? |

| Yarbrough | Mark | 1980 | Broenkow |

| Yoklavich | Mary | 1982 | Cailliet |

| Young | Colleen | 2009 | Harvey |

| Yudin | Katherine | 1987 | Cailliet |

| Yuen | Marilyn A. | 1990 | Broenkow |

| Zamzow | Heidi | 1996 | Johnson |

| Zeiner | Sandra J. | 1991 | Cailliet |