By Jenni Johnson, MLML Vertebrate Ecology Lab

Today, we have another post courtesy of MS 211: Ecology of Marine Mammals, Birds and Turtles, this time from Moss Landing student and author Jenni Johnson. She is going to talk about the hectic but rewarding work involved in elephant seal research at Año Nuevo State Park. -Amanda Heidt Blog Manager

BEEP! BEEP! I roll over to turn off my alarm and read the clock: 4:30 a.m. Begrudgingly I arise, slip into my field clothes, and head to the kitchen to make breakfast before beginning the forty-five minute commute to Long Marine Lab (LML). As I drive north, I mentally prepare myself for the day ahead. Today our focus is assisting with the annual weanling weighing effort. Upon arrival at LML, the field crew assembles all necessary gear, electronically checks into the park, and then piles into the truck. As we cruise up Highway 1 the sky begins to lighten, gradually revealing the charming California coast while the truck buzzes with conversation.

Twenty minutes later the truck pulls into the entrance of Año Nuevo and turns right down the limited access road. The progression is slow as we carefully survey the dirt road for endangered San Francisco garter snakes. I take this opportunity to observe the magnificent landscape, hoping to catch a glimpse of deer, coyotes, bobcats, or the elusive cougar. Alas, no such luck today. Instead, I admire the soft glow of the early morning light and the captivating shades of pink and orange spilling across the sky, signaling the eminent arrival of the sun. I feel excitement start to build as we park the truck.

Grabbing the gear, we hike to the beach, maneuvering through streams, marshes, and dunes along the way. Various animal tracks crisscross over the sand, reminding me that I am merely a guest. The elephant seal calls fill my ears, and I know we are close. We emerge onto the beach as the sun makes its morning debut atop the Santa Cruz Mountains and casts light onto the awe-inspiring scene before us. Pelicans and cormorants congregate on the western point, paling in comparison to the demanding presence of the elephant seals. Nursing females, defensive bulls, dozing juveniles, and curious weanlings cover the beaches and play in the surf. We appreciate this scene for only a moment before setting off to find our first weanling.

Scanning the beach for a good candidate, I can’t help but notice the diversity of rocks, shells, and bones that decorate the sand; untouched by human hands and I absorb the beauty. Within minutes we find a prime candidate, indicated by its unique bleach mark. We set down our gear, delegate tasks, and establish a plan emphasizing the safety of the researchers and animals is paramount then get to work.

One group begins to set up the tripod, attaching the scale and come-along winch to the tripod before anchoring its feet into the sand. Meanwhile, I am tasked with capturing the weanling. For this, a custom-made canvas bag is used to help protect the seal and the researchers as we collect our measurements. Rolling back the seam of the bag, I slowly creep toward the weanling. Suddenly aware of my presence the weanling raises its head to maintain visual contact. Using this to my advantage, I swiftly sweep the bag onto its head. Another researcher steps in and together we carefully wrestle the seal into the bag taking extra care not to harm its flippers. In the process, we expose its belly and identify the sex as male before securing the bag. With impressive coordination, three people position the tripod over the weanling while I connect the bag to the come-along winch via a metal weigh bar. I crank the winch lever slowly lifting the seal until he is completely suspended, record his mass, and then immediately lower him to the ground. Once the weigh bar is removed, the tripod is moved while two of us continue to collect body measurements and a fur sample. Next, we add green flipper identification tags. Two tags are inserted to indicate he has been measured and weighed. Finally, I release the weanling from the bag and estimate percent molt as he galumphs across the sand. Despite what it may seem, the process lasted only ten minutes.

Nine weanlings later, my watch reads 9:15 a.m. and it’s time to depart. On our return hike we encounter a ranger, stop momentarily, say hello, and summarize the morning. Once again, the truck is filled with chatter, this time with questions and lingering thoughts regarding our morning. Upon returning to the labs the gear is cleaned, bags are restocked, and samples are stowed. For the team, this marks the completion of our morning. However, before my morning concludes, I must enter the data. Another forty-five minutes in the car flies by as I reflect on my Año Nuevo morning and silently appreciate the opportunity to experience this wondrous place.

All elephant seal research is performed and photos taken under National Marine Fisheries Service research permit #19108.

Life. I have been lucky enough to have known a lot of kindness in this life. For a long time, I believed I had seen all the kindness - and more - than I could have asked for in a lifetime. And yet, life and the people in it continue to surprise me.

Life. I have been lucky enough to have known a lot of kindness in this life. For a long time, I believed I had seen all the kindness - and more - than I could have asked for in a lifetime. And yet, life and the people in it continue to surprise me.

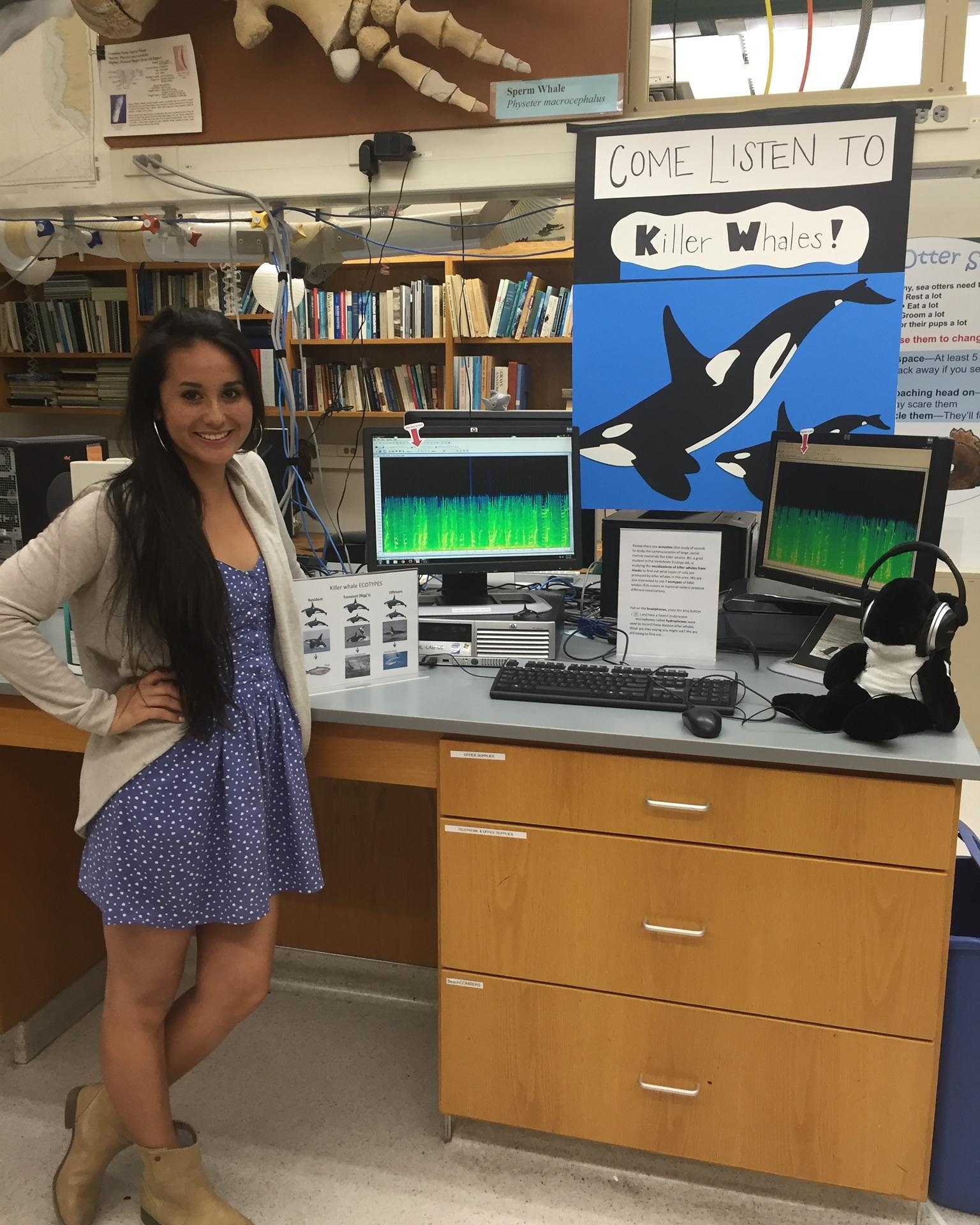

This week's post comes from grad student Bri Madrigal. Bri recently started her own K-12 outreach program called Listen Up! to get kids interested in science and teach about the importance of acoustics in the marine environment.

This week's post comes from grad student Bri Madrigal. Bri recently started her own K-12 outreach program called Listen Up! to get kids interested in science and teach about the importance of acoustics in the marine environment. By Sharon Hsu,

By Sharon Hsu,  By Mason Cole, Vertebrate Ecology Lab

By Mason Cole, Vertebrate Ecology Lab

By Brijonnay Madrigal, Vertebrate Ecology Lab

By Brijonnay Madrigal, Vertebrate Ecology Lab