By Gary Greene ( 21 July 2016)

The Cretaceous-Tertiary (K-T) boundary in geologic stratigraphy marks a seminal time in geologic history, a time when dinosaurs and other organisms were extinguished from the surface of the earth and the rise of new genera and species occurred. A similar type of evolution can be said to have occurred at the Moss Landing Marine Labs, a time line marked by the earthquake of 1989.

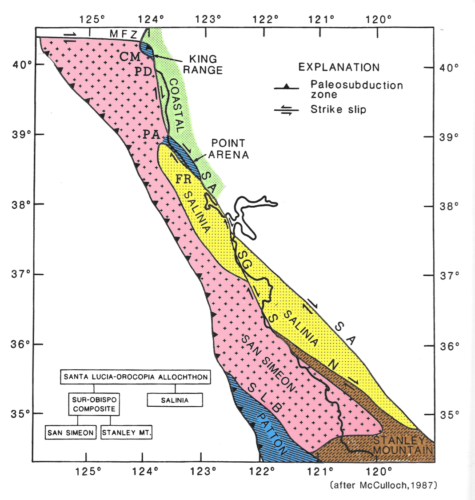

Earthquakes are not unusual along active plate boundaries such as the one that MLML sits on, but they are always a surprise when they occur. This of course is what makes MLML such an attractive place to study marine geology and has attracted faculty and students to the place in the past 50 years. Situated on the Pacific-North American plate boundary at the continents’ edge and overlying a block of Cretaceous granite known as the Salinian Block, the Labs’ geographic location has been transported from where Santa Barbara is located today to its present position since the mid-Tertiary time, in the past 27 million years.

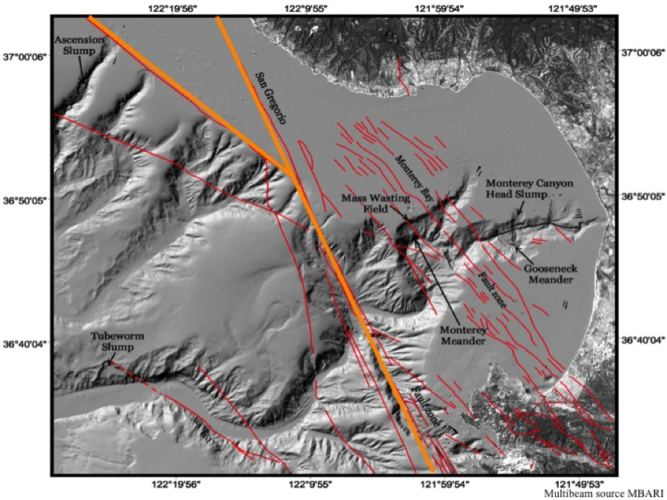

The dynamic edge of the continent is expressed in many faults mapped both onshore and offshore. In the Monterey Bay region the San Andreas is the master plate boundary fault, rupture along which produced the 1989 earthquake, but just offshore of MLML in Monterey Bay are several other active faults, faults of the San Gregorio and Monterey Bay fault zones that control the geomorphology of Monterey Canyon and part of the San Andreas fault system.

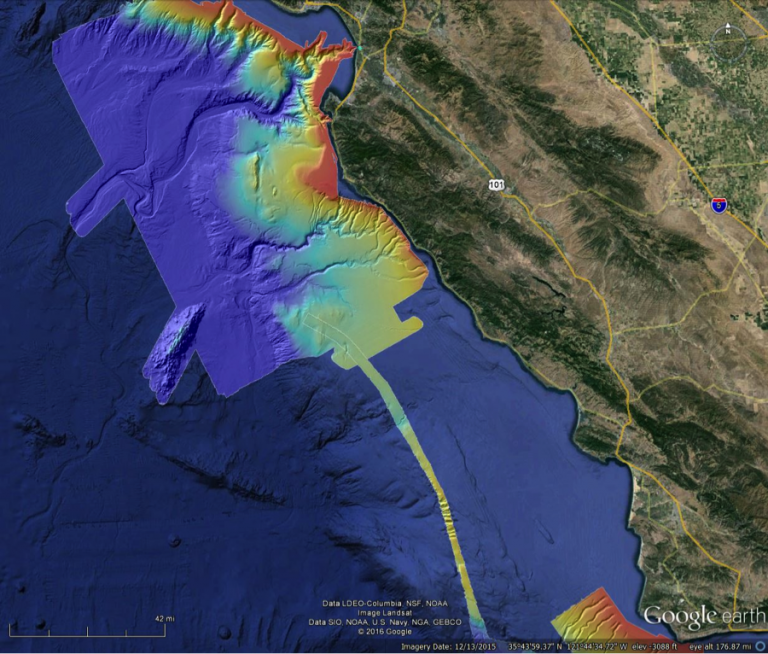

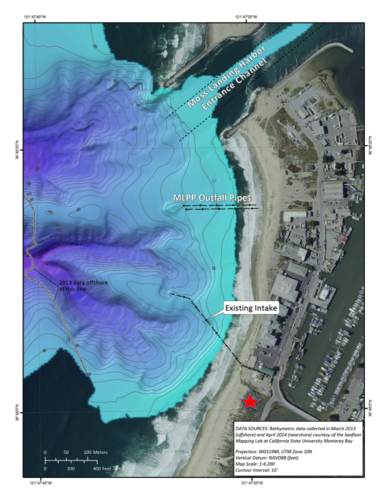

Monterey submarine canyon, eroded deeply into the granitic rocks of the Salinian Block, sits just offshore of Moss Landing and is the largest such feature along the contiguous U.S. It is the size of the Grand Canyon of the Colorado River and its active heads are a stone throw from the beach. Here the canyon heads intercept sand transported along the coastal nearshore areas and sends the sediment down to the abyss. Cold nutrient waters upwell in its heads inviting in marine fauna including whales that feed and frolic in its waters. Fran Shepard, the father of Marine Geology, recognized the geological significance of this canyon in the 1930s and it has been intensively studied ever since, being the most studied canyon in the world. Scientific contributions from students, faculty, and researches at MLML often in cooperation with colleagues at the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute have furthered the understanding of submarine canyon processes.

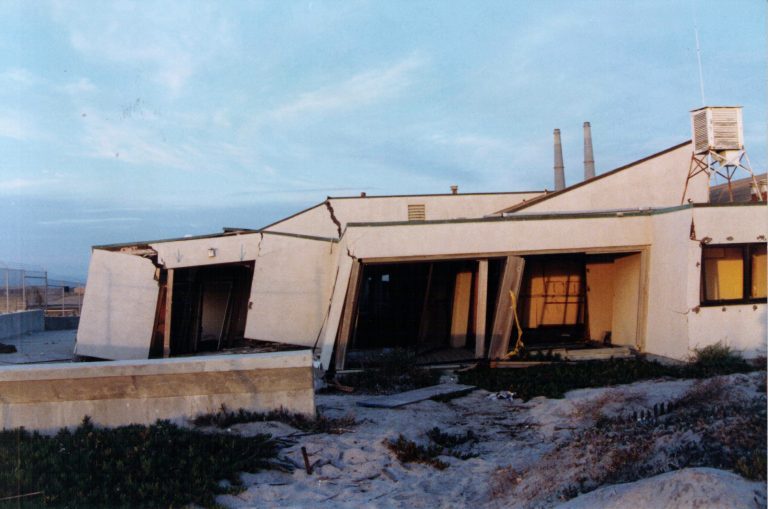

From 1966, when I first came to the Labs to study marine geology, to 1989, MLML resided in a converted cannery and the former Beaudette Foundation’s marine laboratory on the Moss Landing Spit, with the ocean waves lapping at its backside. The library, hosting wood paneling, a fire place, and windows to the sea was a warm, ideal, and inviting snug place in which to learn, and was lovingly overseen by one of the most gracious and welcoming librarians I have ever known, Sheila Baldridge. After the Labs were expanded in the 1980s, the library was moved to an upstairs location in the old cannery building, again overseen by Sheila, where Director John Martin provided the first USGS Pacific Marine Geology field office, which I was able to occupy until the earthquake hit and pulled the Labs apart.

The earthquake, of course, destroyed this quiet, bucolic setting, but it had fostered a hidden strength in its students, faculty and staff, and the community that rose to tackle the rebuilding of the Labs. From the dust, or should I say from the sand boils and liquefaction, was born the: “Friends of Moss Landing Marine Labs,” “Back-to-the Bay” movement, “Save the Water Tower,” and the fight to build a new laboratory, despite “Sally,” Noel Mapstead, and Native American objections to rebuilding the Labs on “The Hill.”

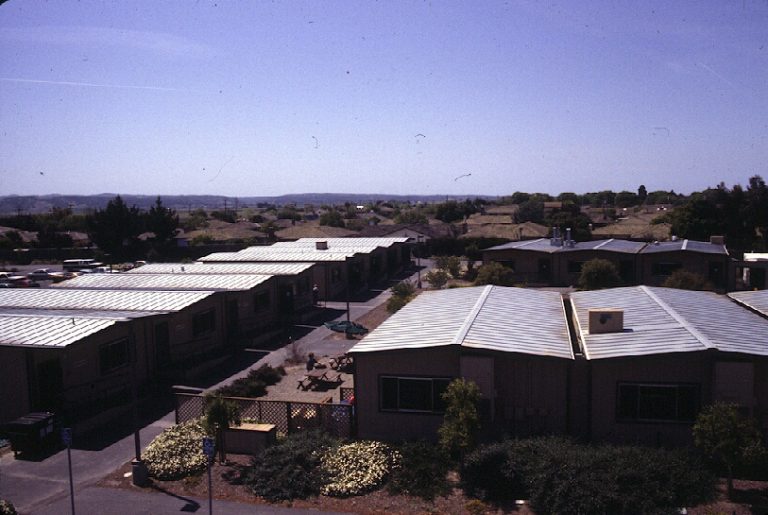

After the earthquake, faculty, staff and students moved to a temporary trailer campus in Salinas, far from the sea and where chocolate permeated the air rather than salt spray. It is a wonder that anyone teaching, studying or working at the Salinas facilities can eat chocolate today. Nevertheless, all persevered with each and everyone connected to, or in support of, the Labs (far too many people to list here), in good faith and selflessly, sometimes on conflicting courses, undertook personal and team efforts to return the Labs to Monterey Bay and to build a lasting institution for the coming generations of students.

It was my privilege to come to the Salinas Labs in 1994 as Director to assist in guiding through the hurdles in the path to the sea. Cloaked in the likes of a larvacean house, a fitting costume for any of the Labs’ Halloween parties at Elkhorn Yacht Club, I appeared on the scene with the intent to filter out the bull s___ (B.S.) that falls from above and pave a smooth path forward. I was pleased to receive considerable support and with this support we were able to turn back opposition. In spite of finding Native American midden remains, and a multitude of legless lizards on the hill, the Labs received the funding necessary for reconstruction (thanks at least partially to the David and Lucile Packard Foundation). The new MLML facility was completed after nearly a decade of struggle.

The time line (MLML’s K-T boundary) was transcended once the new facilities were in place. The faculty had designed a magnificent building, well laid out for teaching and research. It now stands as the window into the ocean and from its expansive backside overlooks the Pacific and the head parts to Monterey Canyon, where geological processes and active marine mammal and bird activity can be observed first hand. Survival of the fittest occurred and new generations of faculty, students and staff are carrying the Labs across its K-T boundary and into a future with great promise. Being on the MLML scene 50 years ago seems like yesterday, but I am a geologist and 50 years is the blink of the eyelid in geologic time.