By June Shrestha and Laurel Lam

Every two years, students and faculty of Moss Landing Marine Laboratories embark on a field studies course in Baja California Sur, Mexico. The field course is intended to give students the opportunity to lead independent field-based research projects in a new environment while promoting international exchange and collaboration. The 2018 class recently returned from Isla Natividad, located off of Point Eugenia on the Pacific coast, with many stories to share! Linked below are the blogs that each student wrote highlighting their experiences in Mexico.

1) Island Life on Isla Natividad

By Jackie Mohay, Fisheries and Conservation Biology Lab

"Imagine; you live in a small community on a remote island in the Pacific Ocean where a hardworking life is simple and fulfilling. One day you are told that a group of 20 will be travelling to your island to study it, using your resources and living amongst you for over a week. The people of Isla Natividad welcomed us with more than just open arms" Read more...

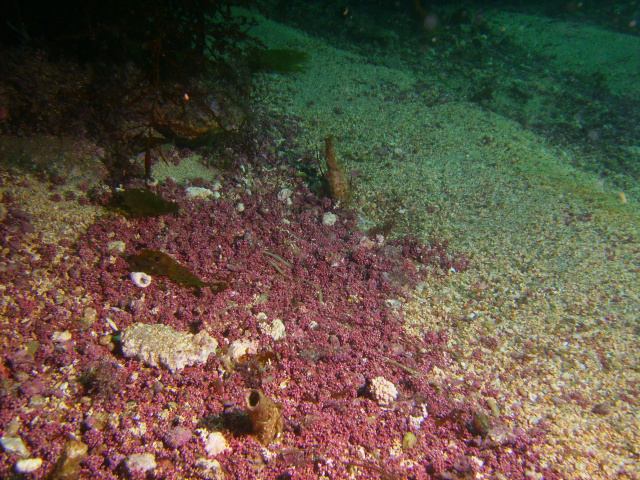

2) And for something completely different... A healthy southern kelp forest

By Ann Bishop, Phycology Lab

"Like their terrestrial counter parts, kelp forests reflect the impacts of the human communities who rely on them. Isla Natividad looks the way it does today because of the careful management practices and intense love the people have for their island. The willingness of the co-operative to learn, flexibility to adapt, coupled, with their ability to exclude poachers has resulted in the rich underwater world we were permitted to visit." Read more...

3) The Journey to Isla Natividad

By Vivian Ton, Ichthyology Lab

"Diving on Isla Natividad was an amazing experience. There were many habitat types such as rock reef, sandy bottom, surf grass beds, sea palm and kelp forests. There was kelp everywhere, the most they’ve had in the past 10 years. Along with the kelp, there were also so many fishes (especially kelp bass) to be seen and quite a few of them were massive in size." Read more...

4) Catching Lizards... For Science!

By Helaina Lindsey, Ichthyology Lab

"Every inch of the island was covered in my chosen study species: Uta stansburiana, the side-blotched lizard. At first glance these lizards are unremarkable; they are small and brown, infesting every home in town and scattering like cockroaches when disturbed. However, if you’re able to get your hands on one, you’ll see there’s more to them than meets the eye. They are adorable, managing to look both impish and prehistoric, and have a brilliantly colored throat. They are heliotherms, meaning that they rely on the sun to maintain their body temperature. I aim to explore the nature of their behavioral thermoregulation, but first I need to catch them." Read more...

5) Life Was Simpler on Isla Natividad

By Katie Cieri, Fisheries and Conservation Biology Lab

"The simplicity of life that results from a unique combination of isolation and intense focus is one of the utter joys of field work. I had toyed with such bliss before... but my elation in Baja California Sur dwarfed that of previous excursions. Perhaps I have matured as a naturalist, or perhaps, as I suspect, Baja is a truly transcendent place." Read more...

6) What does a Sheephead eat?

By Rachel Brooks, Ichthyology Lab

"For my project, I was interested in exploring the variability in diet of California Sheephead (Semicossyphus pulcher) across the island. Once we were suited up, our dive guide Ivan, dive buddy Laurel and I flipped over the side and began our descent through the lush kelp canopy towards the bottom. It took only a matter of seconds before I saw my first Sheephead swim by. Eager to get my first fish, I loaded my speargun and zoned in with little success. It took what seemed like an eternity (20 minutes) before I got my first fish, but when I did, I was overflowing with excitement." Read more...

7) Best-made Plans vs. the Reality of Adjusting to Field Conditions

By Hali Rederer, California State University Sacramento

"My fellow students and I were immersed in rich practical “hands on” experiences integrating scientific field methods with experimental design. This course was comprehensive and the pace was fast. Designing and carrying out a tide pool fish study, in a very short time frame, in a place I had never been, presented challenges requiring flexibility and creative approaches." Read more...

8) Vivan Los Aves!

By Nikki Inglis, CSU Monterey Bay - Applied Marine & Watershed Science

"It wasn’t until the last star came out on moonless night that we heard it. At first, it sounded like the incessant wind whipping around the wooden cabin walls. We heard wings gliding in from the Pacific Ocean and a welling up of some invisible kind of energy. Within minutes, the sound was everywhere. The hills teemed, wings flapped frantically around us. We couldn’t see any of it, but the soundscape was three-dimensional, painting a picture of tens of thousands of birds reveling in their moonless refuge. Isla Natividad’s black-vented shearwater colony had come to life." Read more...

9) Recollections from a Baja Field Notebook

By Sloane Lofy, Phycology Lab

[Written from the point of view of her field notebook] "Hello! I would like to introduce myself; I am the field notebook of Sloane Lofy... As a requirement for the course each student must keep a field notebook so that thoughts, ideas, and notes from the field can be used in their research papers later. To give you a feel for what the trip to Baja was like from leaving the parking lot to coming home I will share with you some of her entries." Read more...

10) From Scientist to Local

By Jacoby Baker, Ichthyology Lab

"Every day we worked with locals, spending hours with them in the pangas, learning the areas where we were diving and what species we may find. Our relationships quickly morphed from strangers, to colleagues, and finally to friends as we shared our dives and helped each other with our projects. The diving was fantastic, but the chance to be taken in by the town and being accepted so fully into their culture was an experience that you can’t find just anywhere." Read more...

11) Snails and Goat Tacos: The Flavors of Baja

By Dan Gossard, Phycology Lab

"Science is not typically described as "easy". This trip to a beautiful, remote, desert island wasn't the easy-going vacation-esque experience one may have expected. Hard work was paramount to collect as much data as possible in a relatively short amount of time. Conducting science at Isla Natividad was a privilege that I greatly appreciated and I hope to return there one day to follow up on my research." Read more...

12) 600 Miles South of the Border

By Lauren Parker, Ichthyology Lab

"If there is one thing I have learned from traveling, it’s that nothing turns out exactly the way you plan it. Tires crack, caravans split up, radios fail, water jugs leak, and you realize that coffee for 20 people cannot be made quickly enough to satisfy the demand. However, beautiful things happen just as often as the unfortunate. Friendships form and others strengthen; new skills are discovered and developed. A flowering cactus forest turns out to be one of the most beautiful things you’ve ever seen. The wind slows and the sun comes out." Read more...

Eager to reminisce about previous trips to Baja?? Check out our previous posts:

- 2016 Class: "Tacos, Takis, and Fish Diet: A Spring Break Saga"

- 2015 Research: "Tales From the Field, Back to Baja: Three Weeks in the Gulf of California"

- 2014 Class: "Bon Voyage Baja Class!", "MLML goes to Baja - the trip continues" and "Projects in Baja - Parrotfish Behavior"

- 2011 Class: To the Field! Mas rapido!, "Islands and Algae and More, Oh My!", "Travel in Style While in Baja", "A Tiny Horse in the Water", "Algae Growing on Algae", and "Hydrothermal Vents: Earth's Natural CO2 Bubbles"