"Fish pee in the sea: a surprising source of limiting nutrients in California kelp forests"

A Thesis Defense by June Shrestha

MLML Live-Stream | December 9, 2020 at 12 pm

Growing up, June always loved being underwater. Long summer days were spent at the local pool in Virginia, where she swam along the bottom pretending to be a SCUBA diver and scouring the “seafloor” looking for treasure: forgotten toys, hair ties, and even a coin or two. Then on a fateful snorkel trip to the ocean with her family, 10-year-old June loved swimming with the fish so much, that she decided that she wanted to be an “Oceanographer Scientist” when she grew up! Mind you, she did not know exactly what an oceanographer did, but she liked that it had the word “ocean” in it, and “scientist” sounded impressive.

From then on, all of her academic pursuits were focused on reaching her goal of becoming an “Oceanographer Scientist”. In high school, she crashed “Take Your Daughter to Work Day” events at NOAA, conducted extra science fair projects, and even studied Latin for four years in hopes that it would help her learn scientific nomenclature. In college, June majored in Biological Sciences for her B.S. degree at Virginia Tech and learned that she was actually more interested in ecology, not oceanography! She participated on any research project she could involving the words “water”, “fish”, or “snorkel”, and spent many days surveying streams for fishes in the mountains of Virginia.

Now, as June graduates with her M.S. in Marine Science from Moss Landing Marine Laboratories and CSU Monterey Bay, she can finally say that she accomplished her childhood dream. When not conducting research, you can find June SCUBA diving - for real now - within the kelp beds of California.

Thesis Abstract:

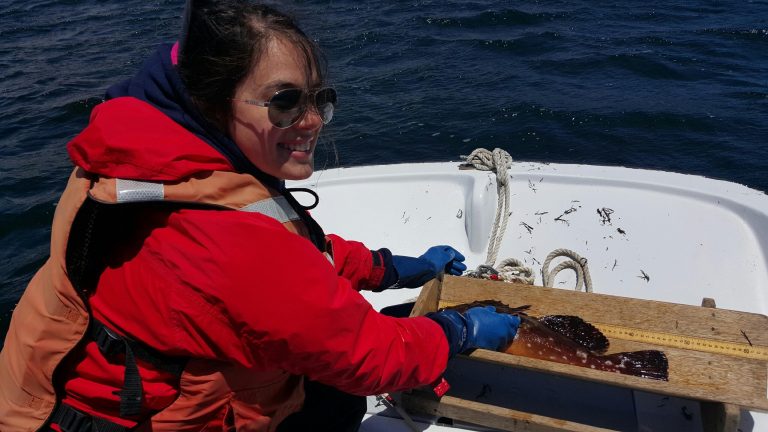

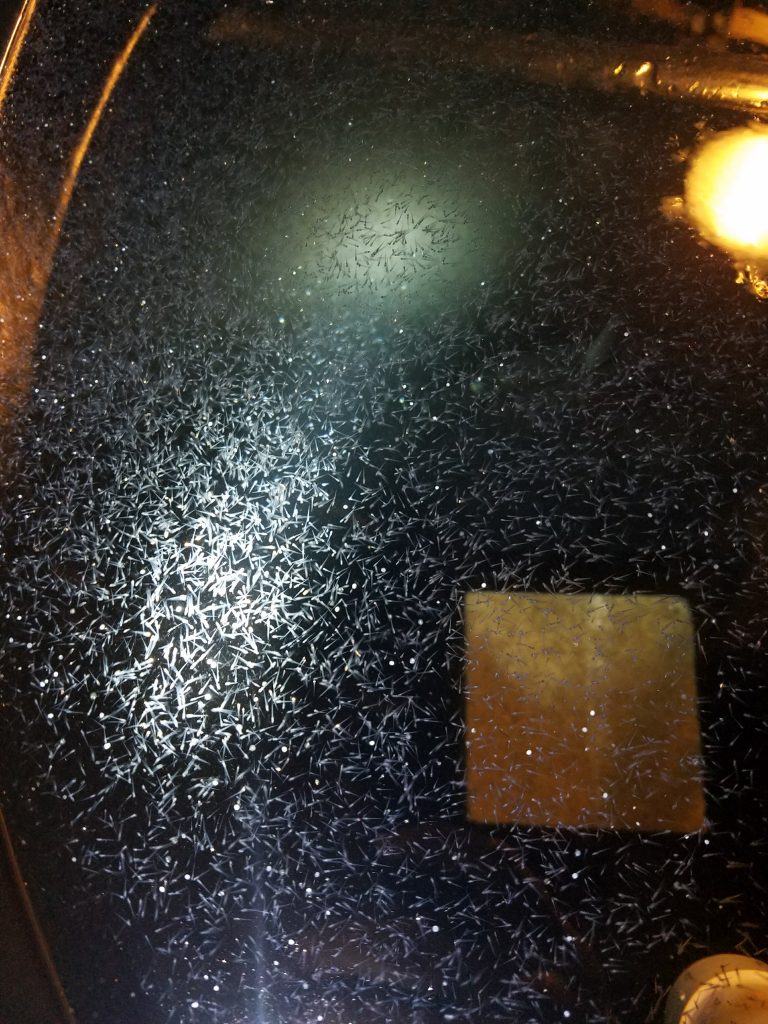

In marine systems, fishes excrete dissolved nutrients rich in nitrogen, a biolimiting nutrient essential for regulating primary production and macroalgal growth in the ocean. Often overlooked in attempts to explain the variability in kelp forest productivity, relatively little is known about the magnitude and patterns that drive nutrient excretion from fishes, especially in temperate kelp forests. I investigated the supply of nutrients excreted by the dominant fishes (30 species representing ~85% of total fish biomass) on nearshore rocky reefs in California. Using rapid field incubations, I measured the amount of dissolved ammonium (NH4+) released per individual (n = 460) as a function of body size and developed predictive models relating mass to excretion rates at the family-level. I then combined the family-specific predictive equations with data on fish density and size structure around the northern Channel Islands characterized from visual SCUBA surveys conducted from 2005-2018. Mass-specific excretion rates ranged from 0.01 – 3.45 µmol g-1 hr-1, and per capita ammonium excretion ranged from 5.9 – 2765 µmol per individual per hr. Ammonium excretion rates scaled with fish size; mass-specific excretion rates were greater in smaller fishes, but larger fishes contributed more ammonium per individual. When controlling for body size, ammonium excretion rates differed significantly among fish families with the highest excretion by surfperches (Embiotocidae). On an areal scale, the fish community in the northern Channel Islands excreted a substantial amount of ammonium to the kelp forest (mean: 131.3 µmol · m-2 · hr-1), and spatiotemporal variability (range: 59.84 – 247.9 µmol · m-2 · hr-1) was driven by the establishment of marine protected areas (MPAs), geographic and temporal shifts in the overarching fish community structure, and environmental and habitat characteristics. Results suggest that fish-derived nutrients may provide an important and underrepresented nutrient source to kelp beds, particularly during low-nutrient periods (e.g. seasonal or climatic events), and that fishing may interfere with these nutrient cycling pathways. Areal rates of ammonium excretion – consistent with those reported for tropical reefs, but among the first measured in temperate systems – reveal that fishes may play a critical role in supporting the resiliency of kelp forest ecosystems.

By

By

Over the past 6 years or so, breaking out of high school biology and into the world of scientific research, is when I realized that creativity and science are not mutually exclusive. They are in fact very closely linked and it might be my creative side that has made me into the scientist that I am today. Like scientists, artists conceptualize and put together ideas in a new way. But instead of observation, facts and data, they use color, shapes, texture, etc.

Over the past 6 years or so, breaking out of high school biology and into the world of scientific research, is when I realized that creativity and science are not mutually exclusive. They are in fact very closely linked and it might be my creative side that has made me into the scientist that I am today. Like scientists, artists conceptualize and put together ideas in a new way. But instead of observation, facts and data, they use color, shapes, texture, etc.

By

By