By Joseph J. Bizzarro (14 July 2016)

Sharks are sexy, sure – but skates and chimaeras are sexy too. You want proof? Well, good (or too bad, because here it comes). This week’s blog is about MLML’s Pacific Shark Research Center, an extremely productive program that was initiated in 2002 and has graduated 25 students and produced > 250 conference presentations, 180 peer-reviewed publications, and 22 books.

Back at the turn of the century, three prominent shark research programs at Mote Marine Laboratory, the Virginia Institute of Marine Science, and the University of Florida were working to secure federal funds to conduct biological research on elasmobranchs (sharks, skates, and rays) with direct applications for fishery management. East coast populations of several shark species were in trouble, mirroring a global trend of severe declines in many species – especially those that are extremely k-selected and/or subject to intense exploitation – and shifts in the composition of skate assemblages. The greatest federal advocates of the program, however, were congressional representatives from California. This was fortuitous for Greg Cailliet, who had a long professional and personal history with the major players from each of the east coast institutions and had carved out his own prominent elasmobranch research program at MLML. Phone calls were made, many long emails were surely exchanged (this is Greg we’re talking about), and behold. In 2001, Congress approved $1.5 million in funding to the National Shark Research Consortium through the National Marine Fisheries Service’s (NMFS) Highly Migratory Species program. With this award the only west coast representative, the Pacific Shark Research Center (PSRC), was born.

At establishment, the PSRC consisted of three staff members in addition to Greg, who served as the Program Director: David Ebert, who acted as Program Manager, and Project Managers Joe Bizzarro and Wade Smith. For the first few years, Joe and Wade were still toiling on their MS degrees while also working for the PSRC. The influx of funding also helped to support MS research for Greg’s ichthyology students who were interested in elasmobranchs, and the targeting of new students whose interests aligned with the goals of the program. These goals were to conduct basic and applied biological research on chondrichthyan fishes (elasmobranchs plus chimaeras, a poorly known sister group to the sharks, skates, and rays), establish the PSRC as a resource center for scientific information on chondrichthyans to public policy makers, provide scientific expertise to NMFS and state management agencies to help better monitor and manage chondrichthyan fisheries off the U.S. Pacific Coast and in Alaskan waters, and participate in collaborative research on national and international issues involving shark, ray, and chimaera biology. Research was focused on addressing major gaps in our understanding of the life history (age, growth, reproduction, and demography), stock structure, ecology, and fishery biology of commercially and recreationally important chondrichthyan species.

“Shark” is a great buzz word – appealing to funding agencies – but in practice, the PSRC could have been dubbed the Pacific Skate Research Center, as the majority of the research has focused on this group of batoids (skates and rays). Skates are exploited in commercial groundfish fisheries throughout the world’s temperate and boreal regions, primarily as bycatch in other fisheries. Despite this incidental take, fishery mortality has altered species composition of skates and caused substantial declines in the populations of many large, nearshore species. Skates were afforded little scientific or management attention in the past because they have not supported lucrative or sustained fisheries. However, this situation is changing because skates are predators and competitors of other commercially important groundfishes, and because dramatic changes in the population sizes of exploited species have occurred. In the water off the U.S. Pacific Coast and in Alaska, management regulations either have curtailed or severely reduced commercial shark landings, but skate bycatch remains a major problem throughout the region, and skate management is therefore a primary concern.

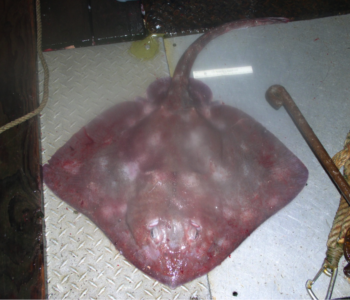

Skates are represented by nearly 300 species of benthic, egg-laying cartilaginous fishes that constitute one-quarter of all extant chondrichthyans. Although they are extremely speciose, skates have conservative morphology, consisting of a dorso-ventrally flattened body and a limited color pallet that includes shades of brown, grey, and black. Skate identification therefore is difficult, and skate species have been historically misidentified or grouped into generalized categories by fishery scientists and managers for convenience. Describing new skate species and addressing current identification problems therefore has been a research priority of the PSRC.

Since 2009, the PSRC has mainly functioned under the direction of Dave Ebert on shoestring budgets, as no steady or substantial source of direct funding has been available. The main objectives of the program remain the same, but Dave began to focus more effort on discovering “Lost Sharks,” poorly known or unidentified/misidentified species and especially those that are exploited in commercial fisheries. This focus builds on some of the major misconceptions of chondrichthyan fishes. The public’s perception of sharks often conjures up images of a large, fearsome, toothy predator, with its large dorsal fin cutting its way through the waters’ surface. However, the reality is that sharks come in a variety of sizes and shapes, from the whale shark (Rhincodon typus), the world’s largest fish, to the dwarf pygmy sharks (Squaliolus spp.). In addition, the batoids and chimaeras have historically received considerably less scientific attention than sharks, but are similarly exploited directly as fishery targets, or indirectly as bycatch.

Our awareness of the diversity of sharks and their relatives has increased substantially in contemporary times, with more than 240 new species described over the past 15 years. This represents nearly 20% of all shark species that have been described throughout human history. Most of these new discoveries have come from the Indo-Australian region, followed by the Western Indian Ocean and western North Pacific regions. However, despite such a rich and diverse fauna, the majority of sharks and their relatives have largely been “lost” in a hyper-driven media age whereby a few large charismatic shark mega-stars overshadow the majority of shark species. While these mega-star’s, such the great white shark (Carcharodon carcharias), receive much media adulation and are the focus of numerous conservation and “scientific” efforts the “Lost Sharks” remains largely unknown not only to the public, but also to the scientific and conservation communities.

Currently, Dave advises 11 graduate students that comprise the PSRC. Joe is back from UW, working with Mary Yoklavich at the NMFS facility in Santa Cruz, and Greg is enjoying his retirement and no longer directly involved in the day-to-day operations of the PSRC. Greg and Joe do, however, collaborate regularly with Dave and his students and have several research projects in progress on chrondrichthyans. The hope is that Dave’s Lost Sharks program will garner the attention of an interested funding agency, restoring a much needed financial infusion to the program. Regardless though, in true MLML fashion, Dave continues to work (gratis) for the PSRC in order to educate MLML students and continue to build our knowledge base about chondrichthyans. The accomplishments and productivity of the PSRC are considerable (see below) and speak to the dedication of the staff and students involved, and their love of these ancient cartilaginous fishes.

PSRC Facts:

- 25 MLML/PSRC graduate students completed their degrees; 13 of these students have gone on and enrolled into Ph.D. programs with 5 having completed their Ph.D.

- Since inception the PSRC has conducted >100 research projects, mostly in the California Current, Gulf of Alaska, and Eastern Bering Sea large marine ecosystems, but also in collaboration with colleagues in Canada and Mexico.

- During this project period we have produced approximately 700 publications (average 56/year) including those that have been published, are in press, or are currently in review; this includes 22 books.

- PSRC Students were lead or co-authors on approximately 350 of these publications.

- PSRC students averaged 10 publications each of all kinds including book chapters, IUCN Red List Assessments, popular articles and electronic on-line publications.

- PSRC staff and students published 180 papers (average 14.4/year) in peer-reviewed professional journals.

- Individual PSRC graduate students averaged 3 peer-reviewed publications each.

- The PSRC has contributed to about 130 IUCN Red List Assessments.

- The National Shark Research Consortium received $11,088,174 in Federal funding from 2002-09.

- $1,400,000 in extramural funding was additionally secured by PSRC personnel, which helped support graduate students at MLML and provided additional support for field work and travel.

- 25 MLML Graduate students were partially or fully supported.

- PSRC staff and students attended over 80 professional conferences and gave 250 presentations.

- PSRC personnel delivered the keynote address at 10 International Conferences.

- Six PSRC students won individual conference presentation awards for best student presentation.

- The PSRC has named 30 new species of chondrichthyans, making us the 2nd leading institution globally for discovering and naming new species.

- The PSRC has discovered 5 chondrichthyan species from off the California coast that had not previously been known.