By Jim Harvey, Lynne Krasnow, Dave Lewis, Judy Johnson, Jack Ames, Tom Harvey, Barry Turner, Chuck Versaggi , and Genny and Shane Anderson (3 December 2015)

One of the early members of the MLML faculty was G. Victor Morejohn, the first marine mammal and seabird specialist at MLML. Dr. Morejohn died on 29 January 2011 at the age of 87. His first name was Gonzalo but everyone called him Dr. Morejohn, Victor, Vic, or MasJuan (but not to his face). He was our major advisor as we went through MLML, and we have lots of stories to tell. He was an old school scientist, a true natural historian with a lot of experience with wildlife and as much experience, if not more, with domestic animals because he had a ranch for most of his life. Kenneth Coale said it well: “He was from an era of marine biological exploration that many in the University IACUC committees could not fully appreciate.”

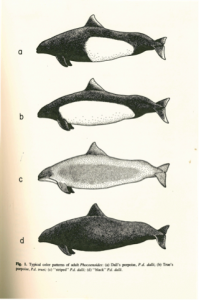

Jim Harvey’s (1978) remembrances: Dr. Morejohn would lecture about marine vertebrates with a piece of chalk in both hands or chalk in one hand and an eraser in the other. He would create the most intricate, precise, accurate, and beautiful sketches of animals (e.g. external morphology, anatomy, physiology, etc.). I would try and replicate them on my note pad and it was pathetic compared with his drawings, and then within minutes his other hand had erased the board and more drawings appeared. You can see many of his works of art in his publications (see below), and I have a small cast of a California sea lion in my office at MLML that was done by him.

I also remember a day on one of the Boston Whalers in Monterey Bay with just Dr. Morejohn and me. I forget why we were out there but at some point I am standing up driving the Whaler as Vic shouts out that there is a White-tailed Tropicbird behind us. As he was expressing what a rare sighting this was, I looked back and then suddenly had the sensation that something was coming my way. I immediately ducked as Vic pulled the trigger on the shotgun with the barrel now over my head. I then asked why he shot something so rare and he said it was not supposed to be here and we needed the specimen. I think the bird is now housed at California Academy of Sciences.

Lynne Krasnow's (1978) remembrances: In addition to his genius in functional anatomy and his artistic talent, Victor Morejohn had a wicked sense of humor. I made a special trip from Davis to meet him when I applied for the masters program and didn't he just have to pull out a box of sea otter baculums (baculi? in any case, penis bones) as a show-and-tell? I must have passed the red-face test because he accepted me as grad student. Even more memorable: when I finished my degree, he took me out with a birding class from SJSU to ensure I was no longer a shorebird collection virgin. I got lucky and downed a shorebird with a single shot, except it fell on the mud. You know, the sticky, sucking mud along the shores of Elkhorn Slough. You can't walk on that stuff, or at least not very far. So Dr. Morejohn slid across the mud on his hands and knees - using the oars from the Boston Whalers as skids - and then carried the dead bird back to the boat in his teeth, with blood dripping onto his shirt. Oh yes, some memories of my time as Morejohn's student will never fade. Happy hunting, Vic!

Dave Lewis’ remembrances: Vic Morejohn introduced me to the wonders of marine science during the 1969 summer session at MLML, where he taught a one-week workshop in marine birds and mammals. It was my first biology class since my freshman year in high school. Because it was only an introductory survey course designed for teachers' continuing education the material was readily absorbed, I did well, and Vic invited me to take the fully loaded birds and mammals class at MLML during the fall semester. It was a stiff challenge for me to stay competitive in that course, but Vic's well organized material and his remarkable lecturing skills kept me motivated, and the course became an epiphany; a personal paradigm shift.

Dr. Morejohn's lectures were amazing to me. He would present a body of factual material, say about the structural modifications of a pinniped flipper, then proceed to the blackboard where after a few seemingly random strokes of chalk a near-3D image of the flipper skeleton would suddenly emerge. He had a magical gift in this regard. Time and again seemingly random lines would coalesce into a coherent image, as if a switch had been thrown. We were all mesmerized by it, and I have no doubt that the effect on us was to more deeply embed the knowledge of vertebrate structure into our brains than any other method could. The pace of his lectures was always controlled so that one could manage to both absorb the material and get complete notes written for reinforcement.

Vic's talents easily merged the disciplines of art and science to create new visions of the world for his students that were greater than the individual components. Whether it was his chalkboard representations of sea lion skulls, his impeccable dissections of cetacean flippers or his bronze sea lion sculptures, his works always seemed to show an enhanced dimension.

Somewhere along the way Vic became interested in marine mammal baculae. I think perhaps he found these useful in paleontological digs, or maybe it was just sublimation (thanks Taffy Stewart!). Regardless, when he retired we had a complete series from his collection bronzed and mounted (Ha!) in a walnut case built by Gary McDonald, which we presented to him at a small but lively retirement bash.

Victor was an old school naturalist that recognized the value of field collection of museum and study specimens. While at MLML he aggressively expanded the teaching and museum collections of marine birds and mammals. He had served with an advance squadron in Burma during WWII (?) acquiring specimens prior to a possible invasion by American troops. His collection activities at MLML were sometimes controversial, most notably the tagging and collection of Dall's porpoises by hand-forged harpoons that he made himself.

The MLML bone yard was a small picket-fenced area where we processed Vic's open-air collection of marine mammal skeletons, with able assistance from his dermestid beetle colony. Squeamishness was not an option there, and Vic and his students endured plenty of aromatherapy prior to its current run of popularity. One day I watched Vic charge out of his office with his shotgun, headed to the bone yard to dispatch a student’s dog that had jumped the picket fence and was chewing on a sea lion femur. Fortunately, mayhem was averted, but we were never quite sure whether he intended to shoot the dog or the student.

Jack Ames remembrances: My most vivid memory of him was his ability to draw on the board with both hands at the same time while lecturing. He lectured with passion.

Judy Johnson's (1972) remembrances: I did go visit him @ his ranch in the Applegate Valley, OR some 15 or so years ago (see attached). He had 1 whole room dedicated to bear skulls that he was doing some research on - it smelled up the whole house.

Tom Harvey remembrances: To characterize Dr. Morejohn as a perfect blend of scientist, rancher, and artist is spot on; his artistic talent most often shown while effortlessly drawing accurate sketches of marine mammals and birds on the black board. Watching him dive into dissection of a beach cast specimen was always a great learning experience and also sometimes an adventure. One of those culminated for me when a 30-foot gray whale came ashore on Zmudowski beach and the class met onsite while he began to cut through the blubber layer into the body cavity. Suddenly, the tissue began to bubble, snap, and tear of its own accord; Dr. Morejohn yelled for us to move back fast as the interior of the whale exploded, belching out gasses and huge coils of dark intestine that boiled out and soon were piled high; burying the very spot where we had just been working. Seeing how he handled specimens it was obvious he intimately knew every facet of these materials and appreciated the wealth of information they contained.

Another memory was of Vic instructing me how I was to extract a family of skunks from live traps I had set while working with colonial birds on the Elkhorn Slough salt ponds. After somehow successfully relocating them with what I felt were only limited mishaps, I was still greeted by him chuckling with raised sniffing whiskers as I entered the room that morning. His lectures were mesmerizing and I still treasure my old class notes. I came as a student in 1975 already interested in seabirds but after a few sessions with Morejohn, I knew I was hooked for life on marine birds and mammals and a career in natural resources.

Barry Turner's (1973) remembrances:

My family had a bearskin rug, passed down through several generations and always used in a cabin in the Sierras. The family always referred to it as a 'grizzly bear'. Eventually the bearskin fell apart but the skull was saved and I ended up with it when I was still a kid. It was an impressive room decoration.

In 1973, near the end of my MLML days, I took the skull in to show to Dr. Morejohn. He immediately recognized that it was not a grizzly but rather a Eumetopias jubatus (Steller sea lion). He was blown away, saying that it was the largest one he'd ever measured, and I gave it to him to add to his collection. He explained that at the time the bear became a rug, grizzly skulls had significant value and taxidermists would switch them for a relatively worthless, but very similar, Eumatopias skull to make a little extra profit on the side.

Dr. Morejohn later told me that he'd sent the skull to the collection at San Jose State College.

Charles “Chuck” Versaggi's (1974) Remembrances:

“Power to the People!” “On Strike, Shut it Down!” 1968 was a tumultuous year of political assassinations, anti-Vietnam protests, campus riots, Black Panthers breaking into our SF State invertebrate class, and college president S.I. Hayakawa losing his wool tam o’ shanter cap to a mob of protesting students.

Intoxicated and stoned with visions of being a marine biologist, following in the steps of Jacques Cousteau and Mike Nelson (Lloyd Bridges of Sea Hunt fame), Moss Landing Marine Labs was the haven I needed to escape the turbulent ‘60s. I came to MLML in 1968, nearly a lifetime ago, as a 22-year old undergraduate from SF State University. With me from SF State were my close friends Gary Carmignani (my housemate at nearby Sunset State Beach), Victor Anderlini, Jim Brenner, Bill Davis, and later, Bud Laurent — part of a group of some 30 students from the California state college consortium that supported the lab.

I was an undergraduate and graduate student through 1974, and Vic Morejohn was my graduate advisor, life mentor and sometimes surrogate father who helped to keep me grounded through those formative years of drugs, sex and rock and roll. During the latter part of that period, I was a graduate student assistant for Morejohn’s marine vertebrate classes; and later, I taught the Marine Vertebrates Class for one semester.

Morejohn’s lectures were a mesmerizing mix of science, natural history, biographical adventure, and sly anecdotes. His unforgettable Walrus-moustache smile, and hairy eyebrow raised behind wire-rim glasses, evoked a hint of “dirty old man,” especially when he proudly showed off his personal stash of marine-mammal penis bones.

Morejohn’s low stature belied his bigger-than-life persona. He was a passionate classical scientist, consummate teacher and brilliant artist. His marine vertebrate classes were a deep dive into marine fish, birds, and mammals — from anatomy to physiology, natural history to ecology — replete with dripping blood, squishy guts, and smelly gore. He was able to engage all of your senses and your imagination, as he recounted his life experiences as an animal collector as far as the South Pole. I would marvel at his ability to simultaneously draw with two hands on the blackboard, seamlessly explaining an anatomical feature and connecting the emerging figure to the animal’s ecology.

The lab section of his classes was where his unique style of teaching and personal narrative came together. Here is where I learned the names of all the bones of a fish by gluing them together, fully mounted like the model airplanes I used to assemble as a kid. I did the same for a bird skeleton (do you know what a synsacrum is?). Corn meal is more than a food staple — it’s what you use to soak up fat when making a study skin of a bird or mammal. Taking his “hands-on” final exam was actually fun (once he put a glob of God knows what on a petri dish, tricking you into a identifying it as something profound and meaningful).

Although I’m not a practicing marine biologist (it took me several more years of schooling and a PhD to learn academic life was not for me), the names of hundreds of marine vertebrates are still burned indelibly into my brain and my love for natural history is unabated. The marine vertebrate lab was where I came to appreciate the beauty of an articulated skeleton, and that bone is a dynamic, homeostatic organ — more than a static structure on which to hang your muscles.

Thanks Vic for the life lessons and wonderful memories — chasing Dall’s porpoises, seeing them eye-to-eye from the bow of a Boston Whaler…conducting smell-quenching necropsies while casually eating lunch on scores of sea otter carcasses (and a few other marine mammals)…the joy of identifying a mystery bird, fish or marine mammal…wind-in-your face boat runs up Elkhorn Slough to watch birds and hauled-out Harbor Seals (sea otters were rare in those days)…gill-netting hundreds of fish for later identification (and eating!)…studying whales aboard the Orca on Monterey Bay, distinguishing their spouts, flukes, and dorsal fins…weekend stays in “the Bunker” on Año Nuevo Island, savoring the sights and smells of northern elephant seals (for you budding mammalogists that’s Mirounga angustirostris)…and late-night runs to the Richmond Whaling Station to collect tissue specimens and parasites from Gray whales as part of a population study by the U.S. Fish & Wildlife (an experience I captured on film, “The Richmond Whaling Station: The Last U.S. Whaling Station.”).

And thanks, too, to MLML for giving me those unforgettable years of enduring kinship with so many vertebrate friends — human and otherwise.

Genny and Shane Anderson's (1971) Remembrances:

Genevieve (Genny) Bockus Anderson with input from Shane Anderson (both students at MLML circa 1968-1971):

Dr. Morejohn was not only a great teacher but someone who took extra time to make opportunities for students. Back in 1969/1970/1971 the Richmond Whaling Station was winding down, taking the last whales killed by the United States (see the story at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Goo2MHirBLs). Dr. Morejohn made arrangements for some of the MLML students to meet the whalers as the dead whales came ashore at Richmond. We were given 15 minutes on each whale before it was cut up (mostly for dog food). We went up to the whaling station many times (2 hours away from MLML) using the MLML carryall. We were organized into different activities to efficiently use the 15 minutes. Scientific data on each whale was taken including all the basic measurements. Then, each of us had a specific ‘project’ that we worked on. I worked on the gray whale’s cyamid amphipods so I busily scooped them into sample jars from the blowhole area, rostrum, genital area and other body areas. Shane Anderson worked on the barnacles so he was busy cutting patches of barnacles off the whale. Ken Briggs, as I remember it, strung white yarn between the fronts of the barnacles and took pictures which showed the direction of water flow over the whale’s surface. I remember Dan Varoujean, Larry Talent, John Hansen, Dave Lewis and Chuck Versaggi were also on the trips (and there were probably others) but I can’t remember their projects and we all didn’t go each time.

Dr. Morejohn actually created a class so we would get units for our studies. It was called “Whale Ectoparasites” – or, in my case ended up on my transcript as DGS (Directed Group Studies) Advanced Studies Marine Science (ML 6903). We all wrote up papers on what we learned for the class. The experience at the whaling station was a rare opportunity and one few marine biologists will ever have. I have two outstanding memories of this awesome experience. First, the smell of the whaling station which nearly made me vomit the first time but after 5 minutes it went away and the only thing to worry about was being careful not to slip on the oily floor. Since that time, when I walk the beach I can smell a dead marine mammal from afar. Second, was the trip when we were transporting a load of whale bones back to MLML, covered with a tarp, on the roof of the MLML carryall. When we stopped for gas we were surrounded by law enforcement officers (can’t remember if it was CHP, Sherriff or Police) who said they had received reports of someone transporting something under a tarp with blood dripping down the sides of the vehicle. (This was the era of the Manson Murders so you can imagine what they thought.) Well, there was a lot of blood dripping down the carryall and it did look pretty suspicious. We students had not noticed this because it was dark. The law enforcement officers were first relieved it was not a grizzly discovery and then impressed with our bloody whale bones. They wished us well but I imagine they didn’t quite know what they were going to find under the tarp and probably had some good tales to tell their colleagues. I have always considered my whaling station experiences to be one of the highlights of my MLML education – a chance to take unique specimens in a unique location and do a research project while contributing to scientific knowledge.

I know that Dr. Morejohn had to do a lot of extra work to allow us to have this opportunity (and we never saw any students from other institutions at the station, so we may have been the only ones to have this unique experience). He was always interested in scientific data, whether at work or on his farm, and encouraging students to be aware of their surroundings. He was one of my role models for teaching and I often thought of him during my 37 years of teaching Marine Biology at Santa Barbara City College where I tried to give my students as much field experience and data taking as possible.

PS Dr. Morejohn also passed on to me his fascination for baculae (mentioned by others). I used this in my classes for extra points for students who could identify a walrus baculum. Only one student in 37 years was creative enough to properly identify this – my students were all freshmen and my class was usually their first marine biology class.

Dan Varoujean adds some more thoughts (7 December 2015):

I do remember the Scotty incident. After informing Morejohn that Scotty's dog had gotten into the bone yard and destroyed one of the porpoise skeletons I had spent weeks cleaning up, he was incensed. That afternoon while sitting at my desk in the museum I heard Scotty berating Morejohn in the hallway, then I heard Scotty screaming and doors slamming. As I went down the hallway I looked into Morejohn's office and noticed his gun cabinet was open and shotshells were on the floor. I ran to the back door, and like you (i.e. Dave Lewis) saw Morejohn pointing a shotgun at Scotty, who was clutching his dog, telling him to put the dog down so he could blow it away. I recall having to provide "testimony" to Robert Arnal (sp?) about this incident. His response was amazing: "I would have shot the dog myself, given he had told Scotty numerous times to keep his dog off the compound". Can you imagine what would happen today to a professor who had pointed a shotgun at a student?

Has anyone told Jim Harvey about Morejohn's Dall's Porpoise harpooning incident? If you recall Charlie Vierra (sp?) had modified a 30-06 rifle by cutting the barrel back so that a harpoon Charlie had made would fit into the barrel. Charlie also loaded up some blank rounds of ammo for use in the rifle. As I recall Baltz was onboard (I don't remember if you or Ken was onboard) when I drove he and Morejohn out over the Monterey Canyon in the Orca. Morejohn was lying on the front deck with the armed rifle in hand when we picked up a school of Dall's, but Morejohn didn't get a shot before the school broke off. Morejohn turned to me and signaled for me to circle back, which I did and as we were joined by the Dall's again he took a shot, but the rifle report was muffled and the harpoon just fell off the rifle. After we had retrieved the harpoon, which was tied to a tire tube with a 10 ft. line, he instructed Baltz to remove the paper wadding out of two of the rounds and double up the powder load. We again picked up the school, and on the first pass Morejohn did not get a shot, but on the next pass he did. This time the report was louder, but again the harpoon just fell out of the barrel albeit a little faster this time. Morejohn then instructed Baltz to triple the load. I remember Don turning to me and saying that the powder now filled the casing and he could barely get the paper wading into the neck of the casing. Both of us, having reloaded our own hunting ammunition, realized that this was probably too much powder, but Morejohn insisted on using this "compressed" load. We again picked up the school and Morejohn fired on the first pass. There was an enormous flash and thunderous report. Both Don and I thought that Morejohn had been seriously injured, but luckily he only burned off his eyelashes, most of his eyebrows and part of his moustache. The Dall's Porpoise was stone dead off our starboard side with a hole in it the size of a softball. Fortunately, the harpoon, which had passed all the way through the chest, had hung up on the carcass so we could retrieve the tire tube and the animal. We later figured out what had happened. When Morejohn didn't fire on our first passes he would raise the rifle and point it skyward as a safety measure until we picked up the school again, which allowed seawater that was covering the harpoon to run down the barrel, soak through the wading and wet the powder. After this excursion, Morejohn determined it was too dangerous to use the harpoon gun, and upon consultation with Baltz they decided we use the harpooning method of their Portuguese ancestors; hence, why we started hand lancing.