Students here at Moss Landing Marine Labs recently founded a local chapter of the Society for Women in Marine Sciences (SWMS). While this group has been doing great work on the east coast for several years, we are excited to bring its success to the Monterey Bay area. Kim Elson is one of several students on the inaugural leadership committee, but she was also the driving force behind the initial push to bring SWMS to Moss. We recently held our first event, a trivia night! Here, Kim offers up some insight into SWMS's history and its future under the new chapter.

Students here at Moss Landing Marine Labs recently founded a local chapter of the Society for Women in Marine Sciences (SWMS). While this group has been doing great work on the east coast for several years, we are excited to bring its success to the Monterey Bay area. Kim Elson is one of several students on the inaugural leadership committee, but she was also the driving force behind the initial push to bring SWMS to Moss. We recently held our first event, a trivia night! Here, Kim offers up some insight into SWMS's history and its future under the new chapter.

Author: mlmlblog

Ms. Scientist Goes to San Francisco

By Amanda Heidt, Invertebrate Zoology & Molecular Ecology Lab

Amanda Heidt was recently selected as the 2018 KQED-CSUMB Fuhs Science Communication Fellow. The Fuhs Family Foundation provided funding for a one year $10,000 scholarship and a paid summer internship at KQED Public Media in San Francisco. She spent the summer living in the city, navigating the BART, and making a map of all the food she needed to eat. At work, she split her time between covering stories for Science News and researching story lines for the popular 4k Youtube video series Deep Look.

Amanda Heidt was recently selected as the 2018 KQED-CSUMB Fuhs Science Communication Fellow. The Fuhs Family Foundation provided funding for a one year $10,000 scholarship and a paid summer internship at KQED Public Media in San Francisco. She spent the summer living in the city, navigating the BART, and making a map of all the food she needed to eat. At work, she split her time between covering stories for Science News and researching story lines for the popular 4k Youtube video series Deep Look.

She recently returned back to the lab and caught us up on what she learned from her crash course in science communication. You can also skip forward here to see her KQED portfolio.

________________________________________________

(Am I dating myself by referencing a movie from the 1930s in the title? Maybe. But don't worry, I'm also hip to the #scicomm lingo.)

I applied for this fellowship on a whim, because the application was only 250 words and the scholarship would be enough to cover the rest of my research costs. Like many people, I think science communication is important, but actually doing it can be completely overwhelming.

But surprisingly, as I cleared the various hurdles they set for applicants, I started to get more excited at the thought of really going for it. I had to summarize a dense scientific paper in 250 words. That was hard. I had to interview with my would-be bosses. Always a nail-biter. And immediately after that, I had to go blind into a two-hour writing test, the details of which I am barred from explaining. It was challenging, but it gave a taste of what it is like to have a quick turn-around on a story.

And I did have some quick turnarounds. My summer fellowship fell right in the middle of an intense fire season in California. As a result, much of my coverage revolved around covering stories related to fires. In these cases, I would be called into my editors office and assigned a particular angle to investigate. For example, the County Fire early on in the summer closed Lake Berryessa businesses during the 4th of July, one of the busiest weekends on the lake. I had three hours in which to find people to interview, call them, transcribe the interviews, write the draft, and go through edits.

But there were other pieces -- longer and more personal -- that took weeks. I was able to be thoughtful in who I chose to speak with, targeted in the questions I put to them, and a bit more lyrical in the way I spun the narrative. I drew from past professional relationships to get at different perspectives. With Deep Look episodes, I formed ongoing relationships with researchers as I came back to them with more questions -- always more questions. While I enjoyed the challenge of a tight deadline, it was clear to me that I was drawn more to the deep dive into a particular story. Maybe I should have guessed as much; my podcast and book choices tend to skew long-term, in-depth journalism.

I think what surprised me most about the fellowship was the diversity of tools in the science communication toolbelt. It isn't just writing. Or even one type of writing. There is, for example, a huge difference between writing a feature piece and drafting a script for a Deep Look episode. A traditional article would largely be a conversation between myself and my editor, but a scripting session was a group affair, with a half-dozen people crammed into a cubicle slashing at a word document as yet another person leaned over to comment from the desk next door.

And beyond the writing, I learned how to photograph and film, how to edit video, how to conduct interviews in-person or over the phone, how to put together a podcast, and how to record a piece for radio. I took photos of people taking photos (it was very meta). I dove with our videographer so we could see where the wild things really were. I wore slacks and a nice blazer to meet a scientist at California Academia of Sciences and then went directly to the beach and soaked myself to get a perfect opening shot.

I loved that there were so many avenues to get the word out. It was fun for me to get to learn about new things, to be a journalistic chameleon for a time. A news story is meant to be factual and timely, while a Deep Look episode is silly and surprising. The immediate gratification of publishing several news stories during my ten weeks is different to the slow-burn of Deep Look releases. My first episode credit released on my last day. They each pull at very different creative threads.

Science communication came to me slowly. Even five years ago, I would never have thought to do anything like this. But similar to the way I think everyone should know the basics of computer coding, I think everyone should have an understanding of how to put words to a page. It's not really so revolutionary a thought; all through school we are expected to learn math, science, literature, history, art. It's only really in college that we move away from what does not come naturally to us.

People invest in what they care about. This, to me, is at the heart of why it behooves all scientists to take communicating their work seriously. Set aside that it can be fun to bring the wonder of discovery to fresh eyes, and you're still left with the fact that we need the broader public behind us to drive forward with our work.

Coming back to the lab, I feel invigorated. And I especially feel affection for this blog, this space that was really my only exposure to writing about science for a wide audience that I had for a long time. Blogging as a legitimate means of sharing information has really only come about in the last decade or so, and I think they retain some of their image as a renegade platform where the words can be yours and yours alone. I am excited, and I hope others are to, to explore the benefits of this creative space. As Erin reiterated in last week's post, this blog has always been for the students, by the students.

Below I've linked to all of my pieces. The application for the next Fuhs Fellow recently opened and will be due in February 2019. I highly encourage any CSUMB-affiliated student to apply. It is intense, but it's also a great way to really jump in to science communication with good oversight and resources. Feel free to email me with any questions.

County Fire Burns Through Many Lake Berryessa Holiday Plans (July 3, 2018)

A Sea Urchin Army Is Mowing Down California's Kelp Forests -- But Why? (July 19, 2018)

California Prison Inmates Battle Fires (July 30, 2018)

Redding Medical Staff Scrambling to Provide Care (August 1, 2018)

Bird Species Collapse in the Mojave, Driven by Climate Change (August 15, 2018)

This Adorable Sea Slug Is a Sneaky Little Thief (August 28, 2018)

California’s Plan to Store Water Underground Could Risk Contamination (September 19, 2018)

A Sand Dollar's Breakfast Is Totally Metal (October 9, 2018)

Sand Dollar Behind the Scenes (October 9, 2018)

Who Are the People Who Run Towards the Stinky Beach Carcass?

By Sharon Hsu, Vertebrate Ecology Lab

By Sharon Hsu, Vertebrate Ecology Lab

My initiation to the MLML Marine Mammal & Sea Turtle Stranding Network was by fire. Actually, by a 200-pound dead harbor seal that we had to drag up Spanish Bay and load into the backseat of Jenni’s Ford Focus, amongst an onslaught of concerned tourists who had just paid to take a leisurely drive down one of Monterey’s most beautiful roads. Surprisingly, despite all the awkward and concerned staring, only a handful of people approached to ask what we were doing. I assume that, like me, everyone else was too shy to ask what the hell we were doing and will forever wonder about that big blue body bag that was suspiciously getting pulled off the beach by two women in flip-flops.

As official dead-thing-touchers (yes, we have the permits to do so – and yes, you have to have a permit to do so), we find that only a few brave individuals will approach to ask questions about what we are doing, and I can only assume that others might be left wondering why two people in a kayak were sampling blubber from that dead humpback whale off Lover’s Point or putting that dead sea lion pup into a plastic bag in front of a class of baby kayakers on Del Monte Beach. So here are the answers to the top six questions we get:

A Happy Blogiversary! Celeblogtion? Blogchievement?

By Amanda Heidt, Invertebrate Zoology Lab

This year we are celebrating The Drop-In's ten-year anniversary! That’s ten years of working hard to give our readers a truthful account of what it means to be a student of marine science conducting our work here in the Monterey Bay.

There are some exciting posts lined up in the coming weeks, but we wanted to take a moment to reflect on the blog’s purpose and the audience it supports.

Erin Loury was one of the co-founders, and she paused in packing for her trip to southeast Asia to chat with me about what motivated her to start The Drop-In.

But first, a bit about her: Erin was originally a masters student in the Ichthyology lab, but she knew right away that her ultimate goal was to attend UCSC’s Science Communication program, a one-year masters degree she describes as “journalism bootcamp for scientists.” As part of her program, she held paid internships at the Monterey County Herald, MBARI, and Science News, the online news arm of Science Magazine.

As she prepared to graduate, she admitted to feeling anxious over her desire to pursue communication without totally foregoing her scientific background. She didn’t want to just be telling the stories of other people, she says, but actively contributing stories of her own.

Erin has now been working for FishBio – a fisheries and environmental consulting company – as their Communications Director for six years. She is able to travel as a fisheries scientist to help with their work abroad and to draft their scientific publications. But in addition, she manages their website, blog, newsletter, and social media channels, prepares press materials, and assists with video production and community outreach.

All of which began with a desire to share stories and a blog that continues today. Below you can read our discussion regarding the blog’s formation and the importance of educational outreach efforts. It has been edited mildly for clarity and length.

What was your motivation to start the blog?

The first was I wanted to create a resource that I wish I’d had when I was a student trying to decide if I should go into marine biology. There are so many young kids that want to be marine biologists, but they don't really have any sense of what that would look like, their families don’t have any sense of what that would look like. They think of being dolphin trainers. But what can you do that kind of degree?

The second aspect was wanting to know specifically what it was like to be a graduate student at Moss Landing. I was trying to encourage the students here to tap into that storytelling and creative side and just being able to share those amazing experiences. Because even just talking to my classmates and my friends, I was hearing about all these incredible trips that people were making into the field and these encounters that they were having with wildlife. It's just such a unique opportunity that we have as marine scientists.

Another important role that The Drop-In can play is helping people understand the scientific process. One of the main things you learn in communication is “show people, don't tell them.” Immerse people in the world of science and help them understand what it means and how challenging it is. It's not just, “Oh, you answered this question, you know everything now.” There's always more questions or sometimes it's hard to answer the question you thought you'd answer. So being able to show people the nuance and the challenge of science as a process is also important.

Where there any challenges to getting the blog running, and if so how did you address them?

In the beginning it was definitely a matter of identity. I think over the years we kind of pared it down to the essence: the students at Moss Landing and sharing their stories, which is ultimately the primary goal of the blog.

But around that time in 2008, there was this growing question of “should scientists be held responsible for doing science communication?” Should they be encouraged or is that solely something that journalists do? And so I think we were starting to see some movement on this idea that we could actually train scientists to be communicators and that some of them are actually really good at it and you don't just have to rely on the journalists to get it right. If you could give young scientists tools to communicate, you’d be turning out better science leaders in the future.

I think there was a concern about potential challenges in the beginning because this was kind of a new thing and I think especially among some of the faculty they just didn't have a clear idea of what it would look like. It was a time when not everyone just automatically knew what a blog was.

One of the things that people were concerned about was comments and the idea of the Internet. What if we got negative feedback and how would we deal with that? And then another was just wanting to make sure we were scientifically accurate. So for a time we had a faculty adviser looking things over, but in the end I don't think we really needed to run anything by her. Once they saw that it was really just us trying to share these stories, that it was promotion for the lab, outreach for the lab, we didn't have any real challenges with that.

What is the value of science communication, and why should scientists care to do it?

The systems that we study as marine scientists are profoundly affected by other people, whether we like it or not. So it's in our interest if we'd like to continue to study the animals, the plants, and the ecosystems that we care about as scientists to be able to get the support and the funding to do that. It's in our best interest to be able to share with other people why we care about these places and why they should care about them and why they're important. I think especially now, when there's so much misunderstanding and a lack of trust of science, that communication can show scientists as people.

That's one of the things that I've learned from the communication world: that people care about other people, you know, they care about the environment as well, but sometimes it's through the eyes or the journey of another person that they come to learn and care about something that maybe they didn't naturally have any interest in.

Amanda Kahn was another of the co-founders, and she is a great example. She studies sponges now. They’re a total snooze-fest to most people. But she is just so animated and excited, she can get just about anyone to care about sponges because she cares about them so much.

What would you suggest to people who want to get some experience in science communication?

Social media is a great tool that you could use to take some baby steps into science communication. I think especially if you're out in the field, Instagram is a really great tool for taking pictures and infusing a little bit of science into your captions. Same for your Facebook posts.

And if you aren't so much into the tech side of things, finding any opportunities for outreach or volunteering where you're interacting with students or with the public, things like Open House. I love working with kids because they're always really excited and very forgiving if you mess up! You have a fun audience to test out your science soundbites on and to help test engaging ways to talk about your science.

Every time you tell a non scientist about the work that you're doing in ways that they can understand, you're doing science communication.

Any parting words of wisdom?

I'm just really excited to see that the blog has been able to continue over all of these years.

I know it can be time consuming when people are so busy in grad school and doing a thesis, but for me having a creative outlet was something that I really valued. Just to feel like you're using a different part of your brain. It can be a fun way, especially if you're dealing with some of the challenges of doing science, to be able to take a step back and reconnect with what drew you to science in the first place. That sort of wonder, that aspect of discovery and learning about nature. I would definitely encourage people to get involved with the blog and use it to test out how they could tell their stories and raise awareness about the amazing work that they're doing.

It was so great to see that Erin was able to find a path that provided so much of what she had wanted going into her professional career.

Coming up, we are putting together a few posts to highlight some of the work our students did over the summer. The script gets flipped for graduate students, as summer is often a time of intense work when field data is collected for analysis in the fall. It is also a time when students participate in short-term fellowships and internships with other agencies.

Let us know, what does science communication mean to you? As a scientist, are you making efforts to share your work with the wider community? As a reader, what would you like to see from us here at The Drop-In?

Tales from the Field: Rhodolith Ecology on Santa Catalina Island

By June Shrestha, Ichthyology Lab

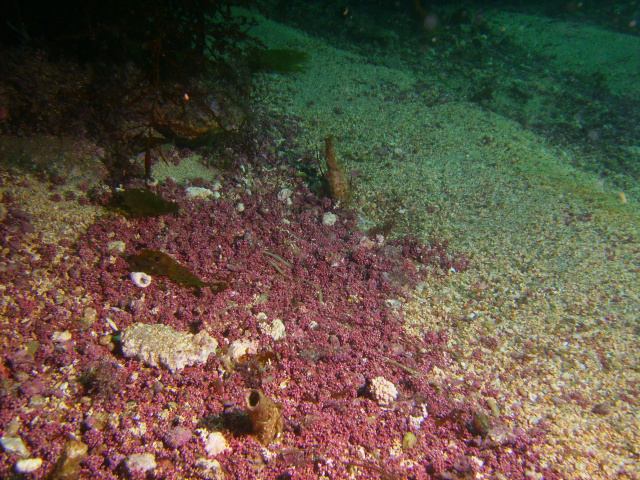

I recently returned from a field expedition to assist PIs Dr. Diana Steller (MLML) and Dr. Matt Edwards (SDSU) research rhodolith beds on Catalina!

What are rhodoliths, you may ask?

Rhodoliths exist around the world, yet not much is known about them. They are a calcareous red alga that provides relief and habitat in otherwise sandy soft-bottom stretches of the nearshore coastal environment, supporting invert and fish communities.

They have been a hot topic in recent years due to implications of ocean acidification on their structure, as well as the fact that they exist in areas with lots of boat traffic and moorings. Interestingly, they are not usually included in habitat characterizations or taken into consideration during MPA designations (which maybe they should!).

Collaboration in Action

The recent research trip was truly a collaborative effort between multiple institutions. Our team was composed of great minds and divers from MLML, SDSU, and even Kunsan National University in South Korea. The research team also featured the one-and-only Scott Gabara, previous grad student at MLML, who is now continuing his research on rhodoliths at SDSU in the Edwards Lab for his PhD (check out his previous Drop-In post about rhodoliths here!)

Further Reading

SDSU Graduate Student, Pike Spector, recently wrote a couple of fantastic blog posts about our work from this trip. I encourage you to check them out for more great pictures and descriptions!

Adventures in Mexico!

By June Shrestha and Laurel Lam

Every two years, students and faculty of Moss Landing Marine Laboratories embark on a field studies course in Baja California Sur, Mexico. The field course is intended to give students the opportunity to lead independent field-based research projects in a new environment while promoting international exchange and collaboration. The 2018 class recently returned from Isla Natividad, located off of Point Eugenia on the Pacific coast, with many stories to share! Linked below are the blogs that each student wrote highlighting their experiences in Mexico.

1) Island Life on Isla Natividad

By Jackie Mohay, Fisheries and Conservation Biology Lab

"Imagine; you live in a small community on a remote island in the Pacific Ocean where a hardworking life is simple and fulfilling. One day you are told that a group of 20 will be travelling to your island to study it, using your resources and living amongst you for over a week. The people of Isla Natividad welcomed us with more than just open arms" Read more...

2) And for something completely different... A healthy southern kelp forest

By Ann Bishop, Phycology Lab

"Like their terrestrial counter parts, kelp forests reflect the impacts of the human communities who rely on them. Isla Natividad looks the way it does today because of the careful management practices and intense love the people have for their island. The willingness of the co-operative to learn, flexibility to adapt, coupled, with their ability to exclude poachers has resulted in the rich underwater world we were permitted to visit." Read more...

3) The Journey to Isla Natividad

By Vivian Ton, Ichthyology Lab

"Diving on Isla Natividad was an amazing experience. There were many habitat types such as rock reef, sandy bottom, surf grass beds, sea palm and kelp forests. There was kelp everywhere, the most they’ve had in the past 10 years. Along with the kelp, there were also so many fishes (especially kelp bass) to be seen and quite a few of them were massive in size." Read more...

4) Catching Lizards... For Science!

By Helaina Lindsey, Ichthyology Lab

"Every inch of the island was covered in my chosen study species: Uta stansburiana, the side-blotched lizard. At first glance these lizards are unremarkable; they are small and brown, infesting every home in town and scattering like cockroaches when disturbed. However, if you’re able to get your hands on one, you’ll see there’s more to them than meets the eye. They are adorable, managing to look both impish and prehistoric, and have a brilliantly colored throat. They are heliotherms, meaning that they rely on the sun to maintain their body temperature. I aim to explore the nature of their behavioral thermoregulation, but first I need to catch them." Read more...

5) Life Was Simpler on Isla Natividad

By Katie Cieri, Fisheries and Conservation Biology Lab

"The simplicity of life that results from a unique combination of isolation and intense focus is one of the utter joys of field work. I had toyed with such bliss before... but my elation in Baja California Sur dwarfed that of previous excursions. Perhaps I have matured as a naturalist, or perhaps, as I suspect, Baja is a truly transcendent place." Read more...

6) What does a Sheephead eat?

By Rachel Brooks, Ichthyology Lab

"For my project, I was interested in exploring the variability in diet of California Sheephead (Semicossyphus pulcher) across the island. Once we were suited up, our dive guide Ivan, dive buddy Laurel and I flipped over the side and began our descent through the lush kelp canopy towards the bottom. It took only a matter of seconds before I saw my first Sheephead swim by. Eager to get my first fish, I loaded my speargun and zoned in with little success. It took what seemed like an eternity (20 minutes) before I got my first fish, but when I did, I was overflowing with excitement." Read more...

7) Best-made Plans vs. the Reality of Adjusting to Field Conditions

By Hali Rederer, California State University Sacramento

"My fellow students and I were immersed in rich practical “hands on” experiences integrating scientific field methods with experimental design. This course was comprehensive and the pace was fast. Designing and carrying out a tide pool fish study, in a very short time frame, in a place I had never been, presented challenges requiring flexibility and creative approaches." Read more...

8) Vivan Los Aves!

By Nikki Inglis, CSU Monterey Bay - Applied Marine & Watershed Science

"It wasn’t until the last star came out on moonless night that we heard it. At first, it sounded like the incessant wind whipping around the wooden cabin walls. We heard wings gliding in from the Pacific Ocean and a welling up of some invisible kind of energy. Within minutes, the sound was everywhere. The hills teemed, wings flapped frantically around us. We couldn’t see any of it, but the soundscape was three-dimensional, painting a picture of tens of thousands of birds reveling in their moonless refuge. Isla Natividad’s black-vented shearwater colony had come to life." Read more...

9) Recollections from a Baja Field Notebook

By Sloane Lofy, Phycology Lab

[Written from the point of view of her field notebook] "Hello! I would like to introduce myself; I am the field notebook of Sloane Lofy... As a requirement for the course each student must keep a field notebook so that thoughts, ideas, and notes from the field can be used in their research papers later. To give you a feel for what the trip to Baja was like from leaving the parking lot to coming home I will share with you some of her entries." Read more...

10) From Scientist to Local

By Jacoby Baker, Ichthyology Lab

"Every day we worked with locals, spending hours with them in the pangas, learning the areas where we were diving and what species we may find. Our relationships quickly morphed from strangers, to colleagues, and finally to friends as we shared our dives and helped each other with our projects. The diving was fantastic, but the chance to be taken in by the town and being accepted so fully into their culture was an experience that you can’t find just anywhere." Read more...

11) Snails and Goat Tacos: The Flavors of Baja

By Dan Gossard, Phycology Lab

"Science is not typically described as "easy". This trip to a beautiful, remote, desert island wasn't the easy-going vacation-esque experience one may have expected. Hard work was paramount to collect as much data as possible in a relatively short amount of time. Conducting science at Isla Natividad was a privilege that I greatly appreciated and I hope to return there one day to follow up on my research." Read more...

12) 600 Miles South of the Border

By Lauren Parker, Ichthyology Lab

"If there is one thing I have learned from traveling, it’s that nothing turns out exactly the way you plan it. Tires crack, caravans split up, radios fail, water jugs leak, and you realize that coffee for 20 people cannot be made quickly enough to satisfy the demand. However, beautiful things happen just as often as the unfortunate. Friendships form and others strengthen; new skills are discovered and developed. A flowering cactus forest turns out to be one of the most beautiful things you’ve ever seen. The wind slows and the sun comes out." Read more...

Eager to reminisce about previous trips to Baja?? Check out our previous posts:

- 2016 Class: "Tacos, Takis, and Fish Diet: A Spring Break Saga"

- 2015 Research: "Tales From the Field, Back to Baja: Three Weeks in the Gulf of California"

- 2014 Class: "Bon Voyage Baja Class!", "MLML goes to Baja - the trip continues" and "Projects in Baja - Parrotfish Behavior"

- 2011 Class: To the Field! Mas rapido!, "Islands and Algae and More, Oh My!", "Travel in Style While in Baja", "A Tiny Horse in the Water", "Algae Growing on Algae", and "Hydrothermal Vents: Earth's Natural CO2 Bubbles"

Adventures in Mexico 2018: Life was simpler on Isla Natividad

By Katie Cieri, Fisheries and Conservation Biology Lab

I stared around at my dusty colleagues, blinking stupidly under the fluorescent lighting of the In-n-Out. Freed from the van which had been my home for countless hours, I found myself suddenly conscious of my briny skin and stiff, desert-impregnated clothes. These trappings of nomadic life, which I had up to this point worn as a badge of honor, felt suddenly dingy and out of place next to the immaculate white and red of the establishment. While I gazed around in disbelief at the hustle and bustle of Southern Californians sneaking a hamburger dinner, a passage from John Steinbeck’s The Log from the Sea of Cortez worked its way up from my subconscious. He writes of himself and his fellow explorers: “The matters of great importance we had left were not important….Our pace had slowed greatly: the hundred thousand small reactions of our daily world were reduced to very few.” Only now, amid the harsh reality of commercial America did I realize the truth of his words- during the past two weeks in Baja my reactions had indeed been reduced to very few.

I couldn’t tell you at what point I first began my transformation from frantic Moss Landing Katie into Katie the easy desert rat. It could have been in strolling in Cataviña among the Seussical wonder of boojum trees, or while floating next to a panga buoyed up by kelp and post-dive euphoria. Regardless of the timeline, I can tell you that the Katie of Isla Natividad had few concerns. Her most pressing questions were: When will I next eat? When will I next sleep? Where are the orange fish? What’s the Spanish word for that? (Luckily for me, on Isla Natividad, the word for Garibaldi, is, in fact, Garibaldi.)

The simplicity of life that results from a unique combination of isolation and intense focus is one of the utter joys of field work. I had toyed with such bliss before in the fanciful rainforests of Australia, or the bright turquoise waters of the Bahamas, but my elation in Baja California Sur dwarfed that of previous excursions. Perhaps I have matured as a naturalist, or perhaps, as I suspect, Baja is a truly transcendent place.

On my boat ride out to Isla Natividad, as I drew ever closer to its brown crags, I must admit that the John William’s score of Jurassic Park was on infinite repeat in my mind. The massive Macrocystis mats stretching before me certainly gave the impression of the Land that Time Forgot. (My later encounters with nocturnos, otherwise known as black-vented shearwaters, certainly built upon this impression. These birds return to the island each evening under the cover of darkness to flap and stumble towards their nest holes. This activity is accompanied by calls that are, in a word, unsettling; they seem to have been inspired by a velociraptor with a sinus infection.)

Amid these splendors, my days on the island had a lulling simplicity. The warm southern sunlight streaming through my cabin window in the morning would wake me. I would stumble awkwardly out into the light and shuffle my way down to the dive locker which munching my morning meal. In an hour or so I’d scramble into the back of a white pickup with my classmates, awkwardly stabilizing SCUBA tanks with my feet as we descended the steep boat ramp. Once aboard a sturdy panga, I’d assemble my dive gear in its startlingly blue interior. Our boat captain, Jesus, would navigate the thick kelp beds with skill, occasionally raising the outboard motor to throw up a shower of water and kelp pieces. On our ride out to that day’s dive spot we might be lucky enough to catch a glimpse of a refreshingly shy sea lion or dolphin.

These rides were breathtaking, but my most treasured moments came in the unique silence that one can only experience on SCUBA. The rhythm of your breathing falls in time with the sway of the kelp and the pulse of ocean surge. As you weave through the kelp forest even the infinitesimal problems that remain with you on Isla Natividad float away with your exhaled bubbles. Emptied of my surface thoughts, I’d set myself to following the pugnacious, yet comical fish that California has chosen as its representative. I hovered above, and beside, and occasionally below these flamboyantly orange fish for countless minutes. Even now, I dream in orange. I timed the often clumsy, yet somehow beautiful dance between a territorial male and his would-be usurpers. My constant vigil was interrupted only by an occasional glace to scribble notes on my slate (white- what a revolutionary color!) or a brief interlude to find another unwitting subject. Garibaldi are, quite honestly, ridiculous, but their desperate self-importance gives them an endearing quality. Their willingness to attack other fish, their own kind, starfish, transect tapes, and even divers that may intrude upon their precious territory is nothing short of foolhardy. But you cannot help but admire their staunch determination. And, while I will never strive to emulate their pugnacious natures, I do hope that my brief time among them taught me something about focus and perseverance.

Eventually these submarine reprieves would be interrupted by my frustrating human need to breathe oxygen. I would haul my awkwardly burdened body back into the boat, rest, and repeat. My eventual return to land each afternoon was as reluctant, but not quite as jarring, as my return to California, USA. Looking back, I can comfortably say, life was simpler on Isla Natividad.

Adventures in Mexico 2018: Catching Lizards… For Science!

By Helaina Lindsey, Ichthyology Lab

I left Isla Natividad with six blisters on my feet, two ways to say “lizard” in Spanish, and thermal ecology data for thirty-seven impossibly fast reptiles.

Every inch of the island was covered in my chosen study species: Uta stansburiana, the side-blotched lizard. At first glance these lizards are unremarkable; they are small and brown, infesting every home in town and scattering like cockroaches when disturbed. However, if you’re able to get your hands on one, you’ll see there’s more to them than meets the eye. They are adorable, managing to look both impish and prehistoric, and have a brilliantly colored throat. They are heliotherms, meaning that they rely on the sun to maintain their body temperature. I aim to explore the nature of their behavioral thermoregulation, but first I need to catch them.

It is 9:00 AM, and I have already been awake for three hours. One of the many secrets to catching lizards is to wake up before they do. Like most people, they are sluggish and slow in the morning, and thus much easier to catch. I stalk around the edges of a dilapidated palapa that sits on the beach in front of our cabins. My lizard-catching partner, Mason Cole, circles around to the other side of the board that I am eying. We each crouch next to one end of the board, taking a moment to make sure that our lizard nooses are ready to go. The nooses in question are crudely constructed metal poles with a loop at the end to tie a slip knot of dental floss that can be slipped over the lizard’s head. We lift up one end of the board and I duck my head underneath it, scanning for movement. I see a small brown flash dart across the sand, and I yell “Lagartija!” We stick our nooses under the board, angling to trap the little guy between the two of us. He puts up a fight, fleeing under another board, then back to the original. Eventually I get my dental floss loop around his neck and jerk up, and the hunt is over. I gently take the loop off the lizard’s neck and flip him over, examining his underside. We record his sex and throat color, then I take the temperature of the lizard and the sand under the board with an infrared temperature gun. Before I take a picture of him, I pull out a tiny bottle of white-out and paint a “23” on his back, marking him as my 23rd lizard caught on the trip so far. I snap a few photos, then place him in the small cooler that is draped around my shoulder. The cooler is filled with the other lizards I have caught today, looking like a team of football players in numbered jerseys.

When we have caught enough lizards, we begin the familiar trek up to the research house where I have been running my experiments. I immediately get to work, setting up my row of wooden tracks with heat lamps at one end. As the tracks heat up, I measure and weigh the lizards before placing them back in the cooler, now with a frozen water bottle to cool them down a little. For my experiment, I am looking at how quickly the lizards heat up and how their behavior affects their body temperature, so I want them all to start at a similar body temperature. I place a lizard in the middle of each track, then cover the track with a sheet of mesh. Because of the heat lamps at one end, each lizard has a temperature gradient ranging from 25o C to 45o C, allowing them to move up and down the track to control their body temperature. After allowing them to acclimate for 5 minutes, I begin taking their temperature every 2 minutes for an hour while also taking note of their behavioral changes.

The last step, of course, is to release them back into the wild, confused but otherwise unharmed. With this data I hope to quantify how the lizards on this island thermoregulate, compare them to other populations of Uta stansburiana, and hypothesize how they may react to climate change and rising global temperatures.

Adventures in Mexico 2018: The Flavors of Baja

By Dan Gossard, Phycology Lab

Life in the Field

After much contemplation, I decided to bring my laptop along on this journey to the unfamiliar coastal desert in Baja California. A laptop would facilitate more efficient data entry at our site and allow for statistical analysis on the return trip. The morning after our arrival at Punta Eugenia, however, made me question my decision. On that day, we packed all of our belongings on a number of panga boats and ferried them and ourselves from the mainland to Isla Natividad - and the journey was fairly bumpy.

Powerful currents and swell defined the "yellow" conditions that were the last categorical color for allowable transit. I was on the last of the boats and all of my gear was sent over on the first boat, which did not ease my nervousness. Once I was aboard the last panga and underway on the wavy route, my unsteadiness was quickly replaced by thrill, excitement, and anticipation. The opportunity to explore an unfamiliar place and dive into a rich and bountiful system is an opportunity not to be missed. If you are presented with that opportunity, prepare wisely, facilitate your safety responsibly, and journey into the unknown.

Our journey thus far had been filled with friendly interactions with the locals at every stop. We ate goat tacos and were pleasantly surprised to discover that they were some of the best tacos we've ever had. Our boat operator was no exception and pleasantly exchanged conversation with the few of us that also spoke Spanish. This conversation was multi-tasked over concurrent concentration and deft navigation through these dangerous waters. This most definitely wasn't his first trip. I wouldn't be surprised if he had thousands of these trips under his belt. Hindsight has provided me with multitudes of questions I would love to inquire of the islanders and their way of life. For someone who thrives in a coastal environment, someone like myself, it seemed to be a very enjoyable way of life.

At the end of the day, muscle soreness was a poignant reminder of the amount of gear we had hauled on these pangas. The local method of hauling gear utilized designated truck drivers to navigate pick-ups into the surf zone to connect with the pangas and transfer gear. As a reminder, metal and saltwater aren't the best of friends - one could say they have a corrosive relationship. The saltwater and the bumpy dirt roads are the likely culprits for the average island truck life expectancy of 3 years. If the amount of gear that was frequently transported throughout the year equated to anything near to what we brought to the island, that was likely another contributing factor.

Research Project

Prior to the start of the trip, I decided to study the most abundant understory kelp (and the only observed understory kelp) at Isla Natividad: Ecklonia arborea. Ecological interactions between understory and canopy kelps have been well established; the niches of the two subtidal kelps E. arborea and the giant kelp (you may be more familiar with) Macrocystis pyrifera overlap along the California and Mexico coast. E. arborea and the giant kelp M. pyrifera compete for resources in the subtidal kelp forest within this range, however M. pyrifera favors colder waters while E. arborea favors southern, warmer waters. Additionally, E. arborea have the capability of persisting in high wave energy environments, which allow them to form forests within exposed areas and within the intertidal zone. Established forests of E. arborea can prevent the inside establishment of M. pyrifera. Oceanographic disturbances such as El Niño events ) favor the understory kelp as well by the combination of warm water exposure and heavy wave action.

I didn't know what to expect, but my 8 days of diving around the island introduced me to a new underwater world. Forests of Macrocystis pyrifera around the 7km by 3km island contained individuals with differing densities. Understory forests contained forests of Eisenia arborea as far as the visibility allowed and further (with exceptional visibility, keep in mind). Within both of these ecotypical forests, the dominant kelp was interlaced with its competitor. Assemblages with these two kelps appeared to vary in terms of the density relationship between the two species between sites (data pending). Field collections of whole individuals at non-protected sites were used to compare some of these appearance characteristics to see whether they vary between sites or whether certain morphological characteristics correlate with others. These collections were analyzed immediately following diving and typically lasted through dinner (even with the gracious help of my colleagues).

The Flavors of Baja

The food at the island was understandably a delicious melange of various seafood. I experienced one of the most exceptional snacks between our daily dives. Surface intervals between dives were accompanied by delicious wavy turban snail treats courtesy of our divemaster and boat operator. The efficient and quick chopping apart of numerous snails' shells with an onboard machete yielded a small bucket's worth of tasty morsels. These snails were less like the escargot from the land and more like an abalone. This treat itself highlights the bountiful harvests that the ocean can yield. Further so, this treat highlights the necessity of managing these resources in order to preserve and allow for their continual use for future generations. The wise implementation of the islanders' Marine Protected Areas illustrates a clarity that I wish was more prevalent in American coastal communities.

Reflections on my experience

Science is not typically described as "easy". This trip to a beautiful, remote, desert island wasn't the easy-going vacation-esque experience one may have expected. Hard work was paramount to collect as much data as possible in a relatively short amount of time. My colleagues and I took apart and measured 137 individuals and conducted 16 dives in a total of 9 days on the island. Conducting science at Isla Natividad was a privilege that I greatly appreciated. I hope to return there one day to follow up on my research with Eisenia arborea.

Saying goodbye is also never easy. The relationships we've developed with the community on the island were very rewarding and positive. I also hope to return to the island just to touch base with the islanders there, be it the island's head of ecotourism, the island's divemasters and boat operators, restaurant owning family, head of aquaculture, our drivers, or the multitudes of others that showed us an amazing time. Our departure marked the end of our time at Isla Natividad, but just another step in our progression as aspiring scientists. We continue forward with our studies with the aspirations to explore and discover the unknown.

Saying goodbye is also never easy. The relationships we've developed with the community on the island were very rewarding and positive. I also hope to return to the island just to touch base with the islanders there, be it the island's head of ecotourism, the island's divemasters and boat operators, restaurant owning family, head of aquaculture, our drivers, or the multitudes of others that showed us an amazing time. Our departure marked the end of our time at Isla Natividad, but just another step in our progression as aspiring scientists. We continue forward with our studies with the aspirations to explore and discover the unknown.

Adventures in Mexico 2018: The journey to Isla Natividad

By Vivian Ton, MLML Ichthyology Lab

It was thanks to the Baja class offered at MLML that I got the chance to travel to Isla Natividad. Isla Natividad is a beautiful place full of life, despite being a small island right off the point of the Baja California Sur peninsula. The people there made you feel welcomed and part of a family. It felt like a mini vacation rather than work as time slows down there as you sit in front of your cabin that is facing the beach and watching the dolphins swim by.

The Journey

While there are many ways to go down in Mexico and get to Isla Natividad, preparations must be made beforehand. It took months of planning and working out the logistics. Everyone had a role and a research project to conduct while on the island.

We left early from Moss Landing, stopping in San Diego for the night. From there it was a scenic route to Ensenada. Ensenada was a bustling city and it was there where we met Andrea and Jeremie, fellow graduate students from Mexico who’ve joined our trip. Jeremie showed us his favorite place for fish tacos and they were delicious!

Once we’ve had our fill we left for Cataviña, a desert valley full of endemic succulents and cacti.

The trip there was quicker this time around passing into Baja California Sur by the afternoon. We were rushing a bit since conditions for the ferry weren’t looking good and would only going to get worse later that day. However, the fishermen from Isla Natividad managed to pick us up in the end. It was a little scary going full speed through the waves and there were times where I was lifted off my seat and my feet wasn’t touching the boat, but our driver was skilled and got us to the island safely.

Island Life and Research

Once we were onto the island, everything seemed to have calmed down, literally. The wind wasn’t blowing and the sun was out and shining. Our guide, Mayte, the head of ecotourism on the island gave us a tour of the island. The views were breathtaking and I love how everyone knew one another and chatted as we walked by.

Over the next week and a half, those of us with projects in the water dove practically every day. Diving there was an amazing experience. There were many habitat types such as rock reef, sandy bottom, surf grass beds, sea palm and kelp forests. There was kelp everywhere, the most they’ve had in the past 10 years. Along with the kelp, there were also so many fishes (especially kelp bass) to be seen and quite a few of them were massive in size. The Sheephead there were the largest I have ever seen. I was also lucky enough to see a couple rare and tropical fishes such as the longnose puffer.

My project was to compare total fish abundance and communities inside and outside of the MPA (marine protected area). Isla Natividad is special in that it has two MPA under its jurisdiction. These MPAs were created recently in 2006 and was set place by the people living there. The people of Isla Natividad are mainly fishermen where invertebrates are their main source of income such as abalone, lobster, octopus, wavy turban snails, and sea cucumber. Although there are fin fisheries around to a smaller extent, finfishes are mainly caught for subsistence. While Isla Natividad fishermen have exclusive rights to fish for invertebrates within Island waters, anyone can catch the fishes as long as they have a permit. MPAs are important in protecting biodiversity and the ecosystem within it. Some benefits for implementing MPAs include higher ecosystem resilience against storms, creating essential networks and refuge for fishes and invertebrates, and increasing total abundance and biodiversity of kelp forest organisms, causing a spillover effect for fishermen.

Anyone with a diving certification should dive there at least once, you won’t be disappointed. By the end of our stay it felt like we have been living there for months as we got used to the island life and I was sad to go when it was time to leave. I had a lot of fun at Isla Natividad and would like to thank the people of Isla Natividad for helping and lending out their facilities to us during our time there. I hope to visit them again in the future!