By Tim Herrlinger (7 December 2016)

MLML graduate students travel many financial paths along their educational odyssey to obtain an advanced degree. Often these endeavors are undesirable, but the key is to balance risk and reward.

The Beginning

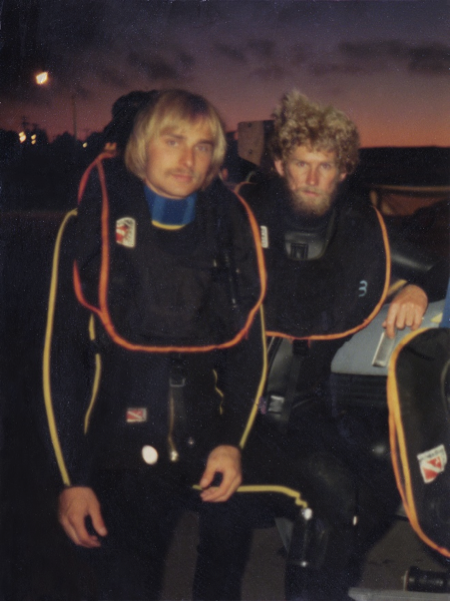

Mark Carr introduced me to the world of SCUBA diving for pay. He showed me I could use my diving skills to make money on the side and help pay the bills. Describing Mark as an agent, a promotor, an enabler, or a hustler wouldn’t be far off the mark.

In March 1980, someone from General Fish Company came over to the lab and asked if a diver could cut a net out of the prop of the New Janet Ann II (a drag boat/trawler). The skipper probably backed down on the net and wrapped it several times. Mark and I went over to a Moss Landing harbor slip, donned our gear, jumped in, and started cutting out the net with knives. We could barely see our fingers in the near zero visibility. It was dangerous work since we kept getting our tank valves and regulators tangled in this massive net. After two hours underwater, we got the job done. Mark recalls: We went back to the lab to wash our gear while the owner went to get cash. But when we returned, the boat and the people who hired us had left. We got stiffed!

Having learned my lesson, I demanded $30 just to get in the water for my next job in September of the following year. An electronics shop next to Great Western hired Guy Hoelzer and me to install a sonar unit on an albacore boat from San Diego, the Quicksilver. Knowing nothing about what I was doing, I relied on their topside guidance and it took an hour in the murky Moss Landing harbor water. Guy and I were each paid $100 and we had made it to the big time. Sadly, eight years later the Quicksilver sank while fishing off Vancouver Island and four crew members perished in a storm with 40-50 kt winds and 20 ft seas. A surviving crew member held his dying son in his arms just minutes before the father was rescued.

International Shellfish Enterprises

Four days later, John Heine asked me to help him with a paid diving job for International Shellfish Enterprises. ISE was a mariculture facility with an intake on the west side of the Moss Landing peninsula. It took us three dives to install a very long 3 inch black ABS flexible pipe for their new intake. We were in 15 ft of water and the surge was incredible. At best, the underwater visibility was 5 ft and we were pounded by every six ft swell that passed overhead. We attached concrete parking lot bumpers along the entire length of the pipe to weight it down. We worked from 5 AM to 1 PM and earned $50/hr for our total time, including washing up dive gear.

While Mark Carr was the initiator of my paid diving adventures, John Heine would have to be considered my benevolent pimp. John and I made a total of 12 dives for ISE over two months. We added a dozen more parking lot bumpers to the 3” pipe (which had floated to the surface) and then graduated to deeper dives on ISE’s 6” pipe. We cut the larger diameter pipe at 70 ft to remove clogs and added a giant metal “A” frame to keep the end off the sandy bottom. The money was very good, helping to offset school costs, and allowed me to upgrade some of my dive gear.

On October 5, 1981, John and I made a dive in Moss Landing Harbor on an albacore boat, the Sharron. With the help of their winch, we used a crowbar to free a stabilizing fin. We also changed their zincs* and earned $100 apiece for 30 minutes in the water (1.5 hours total time). But an experience two weeks later almost cost me my life.

*Boats in seawater are susceptible to corrosion when dissimilar metals on their underside act as a battery. Sacrificial zinc anodes are bolted to the hull or trim tabs and dissolve over time. These zinc bars need to be changed periodically and it’s a fairly simple process with a wrench. A diver can swap out zincs in a few minutes compared to the cost of pulling a vessel out in a boat yard.

The goal of the work that Tuesday (10/21/81) was to place a cone on the end of the 6” pipe that was near the submarine canyon in 70 ft of water. The ocean was cooperating with only a 2-3 ft swell and John and I swam the cone out on the surface. We wanted to drop down where we thought we’d find the end of the pipe. Before the advent of GPS, we used a pair of visual shore line-ups to note when a near object was in front of a more distant landmark. That would put us in the vicinity of our desired location. We descended and went to 90 feet without hitting the bottom. We were too deep and started our ascent to try again. Once or twice at 70 feet on the way up, my regulator gave me only half a breath. On the second try we were still too deep and my regulator was still occasionally hard to breathe on every few breaths at about 70 ft. We tried the line-ups again and hit the bottom on our 3rd attempt. The visibility was surprisingly good – an impressive 10-15 ft. The cone had a rope tied to it and we used it to do a circle search to try to find the end of the pipe. It only took us a few minutes to find the pipe after widening our search to a diameter of 20 ft. We worked hard to get the cone on the pipe and tie it off. Meanwhile, my regulator was getting worse and I made sure John was right next to me. After 10 minutes on the bottom, I finally couldn’t get a full breath no matter how hard I sucked. My regulator had essentially quit. I gave John the out of air sign (drawing a finger across your throat) and we began buddy breathing where we shared the second stage of his regulator. We started swimming up together and I was anxious to get to the surface. At 60 feet, John vented my buoyancy compensator so that I wouldn’t rocket out of the water and embolize. I was wearing a 32 lb weight belt because of the strong surge we normally encountered, and now I had to kick even harder to make vertical progress. Normally the donor takes two breaths before passing the regulator to the receiver for his two breaths. But I was honking 4-5 breaths for every 2 John took. I was almost gasping for air because I was so breathless and thought we’d never make it to the surface. At 30 feet, I fought the strong urge to ditch our buddy breathing and just swim for it. I was very close to panicking. Luckily we both stayed under control and the surface air never tasted so good in my lungs. John had just saved my life.

I had my regulator serviced and continued to do odd diving jobs. I worked on the New Janet Ann II again and cut a steel-belted tire and rope (from a side bumper) that made six wraps around the propeller and along one foot of the shaft, earning $75. The gravy train of the ISE work finally ended in November, and on December 2nd I shifted to helping Mark Silberstein clean the MLML Seawater Intake with an iron bar and pneumatic gun.

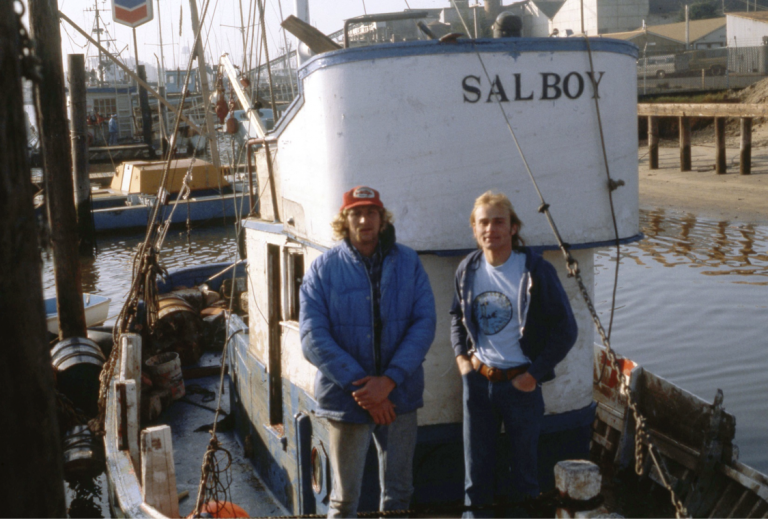

Raising the Sal Boy

A new harbor adventure greeted me on January 15, 1982. Over the holidays, a purse seiner named Sal Boy had been tied up to the dock next to the Moss Landing Boat Works (a boat hoist where boats were hauled out). Perhaps because of loose lines, the bow likely caught under the dock with a change in the tide and the boat sank. It sat in the harbor for weeks while the parties argued about who was responsible. Vito Ferrante, the skipper, hired me to help refloat the boat and I asked Gilbert Van Dykhuizen to assist.

Our first attempt to raise the boat involved using two truck tire inner tubes. When we tied the inner tubes to the deck railings and filled them underwater with an air hose, the large tires were sitting at the surface and didn’t provide lift. We needed to attach them lower on the boat, closer to the hull, which was sitting on soft sediment in 15 feet of water. The next idea was to tie the inner tubes to the propeller shaft. Heavy rains since the sinking had packed silt and mud against the hull. I went down near the keel in 1 ft of visibility and tried to tie a line to the shaft, but it was under the mud. I started excavating and kept putting my hands into all kinds of debris including fish bones and other sharp objects. I finally got close to the shaft, but had to wedge myself under the boat. It was a scary and stupid thing to do. If the boat shifted, I would be trapped. I finally got the line around the shaft and we filled the inner tubes. The boat didn’t budge.

Vito’s cousin Tory attempted the next plan of attack by putting a waterbed mattress in the boat’s hold. While it filled with air, the mattress caught on a nail or other sharp object and popped.

Plan number three involved tying a come-a-long winch to the pier and ratcheting the boat up. We raised the bow somewhat, but the vessel was still stuck on the bottom of the harbor. We decided to give up for the night and regroup at 8 AM the next morning.Idea number four involved using 55 gallon steel drums to provide lift. A crew welded metal eyelets on the ends of the drums where our lines could attach. We tied the drums as close as possible to solid areas of the boat deck, added air, and capped them off. It took most of the day to add 14 drums, and to our surprise, this technique was actually working! The boat came up a lot, but there were three places water could enter before we could start pumping: the hold, the engine room, and the cabin. Gil helped tie the boat to a truck and the vessel was dragged as close to land as possible, but much of the boat was still underwater. We hoped a drop in the tide would help lower the water below the three openings. We sealed off the hold and the engine room was now above water. We succeeded in boarding up the cabin as low tide approached, two hours before midnight. Now the race was on and we started pumping for our lives. Gil and I were afraid we wouldn’t get paid unless we actually floated the boat. We had to keep plugging holes in the port windows and fuel openings on the deck. Progress was slow until the boat suddenly started rising fast. The keel had finally been freed from the mud. It wasn’t until around midnight when the Sal Boy had returned to the surface.

The next morning there was only 1 foot of water in the compartments after we had pumped it dry the following night. The Sal Boy was hoisted out of the water and our mission was complete. Gil and I were paid a total of $650 for the two days of work. We were exhausted, but felt as rich as kings.

By now, I was an experienced boat refloater and on February 16, 1982, I was called to raise the 35 ft Barbara, another fishing boat that had sunk at B-dock in Moss Landing Harbor that morning. Recall that 1982-1983 was a strong El Niño. Allan Fukuyama and I attached two tractor tire inner tubes to the deck cleats and raised the boat enough to put a line under the keel and around the shaft. We tied two more inner tubes to the line going under the boat and it was enough to float the boat where it could be beached. Allan and I split $250 for two hours of work in zero visibility.

The R/V Cayuse Bow Thruster

On April 6, 1982 the crew of MLML’s R/V Cayuse asked me to dive on their ship to examine the bow thruster and see if it was operating properly. They had been in San Francisco Bay and hit something. Alistair Hamilton and I jumped in the water at Moss Landing Harbor where the Cayuse was docked. The visibility was only 9 inches, but I could see that the bow thruster propeller was completely gone. Three bolts had been sheared off and one was missing. I used Vise-Grip pliers to remove one of the bolts that was sticking out. The other two bolts were snapped off inside and I used a chisel and hammer on the outer edge of the bolts to slowly rotate them. When enough threads were finally sticking out, I was able to grab the bolts with the Vise-Grips. The crew were very thankful and told me I had saved them several thousand dollars in haul-out costs. Then they offered me a six-pack of beer. Needless to say, this was not my usual remuneration and the lab eventually gave me $100.

Rescuing the Seismic Profiler

Around sunset on April 22, 1982, Dave Schwartz came running into the lab and was frantically trying to find help. Hank Mullins and Dave had taken a new seismic profiler out in a Boston whaler to examine the subtidal geologic features near the mouth of Elkhorn Slough. The apparatus was bulky and consisted of several parts kept in the boat and a large uniboom sled towed behind. Compressed air blasts from the uniboom are directed to the ocean floor, hydrophones receive the signals, and a geologic profile is generated through computer processing. On this day, the yellow and blue uniboom sled was trapped below the surface and the large black cable connecting it to the equipment in the boat was hung up on something underwater.

At 7:00 PM, there were few people still at the lab. I was the only diver and didn’t want to do a night dive in the harbor by myself. But Dave pleaded with me saying that Hank needed to be rescued because the tide was coming in and the whaler might sink. They would lose several thousands of dollars of equipment if they had to jettison it. I grabbed my dive gear, loaded it into a lab vehicle, and Dave and I headed over to the Highway 1 bridge. I jumped in the water from a dock at Maloney’s Harbor Inn on the northwest side of the bridge and started swimming parallel to the bridge to get to where the whaler was positioned. But almost as soon as I left the shore, there was a tremendous incoming tidal flow roaring under the bridge. It was so strong that I barely made it to the bridge’s first piling and just clung on. If I had missed that bridge support, who knows how far I would have been swept into the distant reaches of seven-mile Elkhorn Slough – at night!

Meanwhile, back at home in his house at Sunset Beach just north of the lab, Dave Nagel patiently waited for Hank and Dave S. to show up for dinner after their long seismic profiling field day. Dave N. had cooked a nice chicken dinner and became worried when the two researchers were well past their arrival time. Dave N. turned down the oven and headed to Moss Landing. When he drove over the slough, he saw Hank and the whaler hung up near the Highway 1 bridge. Dave N. stopped and walked on the bridge, called out, and saw that I was in the water with my SCUBA gear. Both Daves, now working together, threw me a rope.

Unable to swim against the very strong tidal current, I held onto the rope while my support team dragged me from piling to piling. Each time I let go of a bridge support, I disappeared and was sucked under the bridge until both men pulled me back out to the next piling. Eventually I got to the whaler on the channel side of the bridge. Then, while climbing into the whaler with all my dive gear, I lost my weight belt. Dave S. went back to the lab and got me another one. I then went down the cable attached to the uniboom and the bridle was caught on an old submerged wooden piling about 10 ft below the surface. The cable was also wrapped around a second piling that was deeper. I untangled the cable from both pilings and it floated free. We were now drifting in the current.

Weight belts were expensive and I came back about half an hour later with a dive light and searched underwater trying to find my weight belt while I held onto a line. Thirty minutes into this dive, the current had slackened and I found my belt. Dave Schwartz asked me to take two core samples at a depth of 30 ft under the bridge for his thesis and I obliged. Anything for science!

Eventually word got out about the calamity in the harbor and we had to face the music. John Heine, our Diving Safety Officer, mildly chewed me out for diving solo, but understood that I was in a tough position. Hank probably got the worst of it and received a rather stern dressing down from our director, John Martin. I felt proud that I had rescued the lab’s equipment, but acknowledged it was a dangerous stunt. Many things could have gone wrong, and almost did, but thankfully it all turned out well – except for the charcoal chicken dinner.

Diving for Food

Money wasn’t the only commodity involved in being a rent-a-diver. Once while we were tied up on the outside edge of the Hopkins kelp forest preparing for a research dive, a fishing boat approached us. The skipper asked if someone could cut kelp from his propeller. I jumped in and spent a couple minutes cutting Macrocystis from under the stern. I was very pleasantly surprised when the captain rewarded me with a bucket of fresh spot prawns (Pandalus platyceros) which I subsequently used as leverage when suggesting a romantic dinner that night. Another time I was again anchored along the outer Hopkins kelp canopy with different dive buddies and I saw the same fishing boat bearing down on us. I quickly began putting on my dive gear and my boatmates became worried, thinking I was abandoning ship. Of course the boat didn’t ram us and made a quick turn at the last minute. On this occasion we were asked to change the zincs on the underside of the hull. I wanted to be sure that I was the first one to provide the services, knowing there would be a sumptuous prawn reward. That bonanza evaporated as I never saw the boat again.

Addendum (Shark Story)

When you tell diving tales, everyone wants to hear a shark story. I’ve got a few, but none occurred while I was underwater at Moss Landing. The one MLML ocean shark story I can share occurred in the early 1980s. I wasn’t that into volleyball and requested SJSU Student Activity funds to buy a lab football. Todd Anderson, John Heine, Mickey Singer, Joel Thompson, Allan Fukuyama, Bruce Welden, Guy Hoelzer, Don Canestro, Mark Carr, Alan Lewitus, and others would go out to the beach next to the old lab and we’d play football on the sand. We used a stick to draw a line in the sand or put kelp or other debris up near the high tide wrack line to mark one of the out of bounds sidelines. The other sideline was simply the water. If you caught a pass and ran into the ocean, you were out of bounds and play stopped. One afternoon, John Heine had the ball and ran into the water. He yelled to us that he saw a shark! We were skeptical and wanted proof. But lo and behold, there was a shark thrashing around in the surf zone. For further validation, John decided to show it to us. He reached into the water, grabbed it by the tail, and tossed it up on the sand. It was a live, 3-4 ft blue shark. After a minute or two, he pitched it back in the water. Later, he lamented not keeping it as a data point for the MLML Shark Aging Research group.