By Scott Miller

Some of you may have been following the blog way back in March, when the “Baja class” traveled to the Gulf of California for two weeks in the field (as a refresher, you can check out the previous posts here and here). Jackie promised some photos and stories from the trip, so I’m going to highlight my particular research project down there and toss in a few of my own photos (better late than never, right?)!

Panoramic view from our campsite on the beach at Bahia de Concepcion, our second of three overnight stops in Mexico on the way down to El Pardito.

Our trip wasn't all marine science! We stopped in the desert on the way down for a natural history lesson from our knowledgeable professors, where we learned about desert ecology and geology!

El Pardito provided some stunning views of the sunrise from the top of the island.

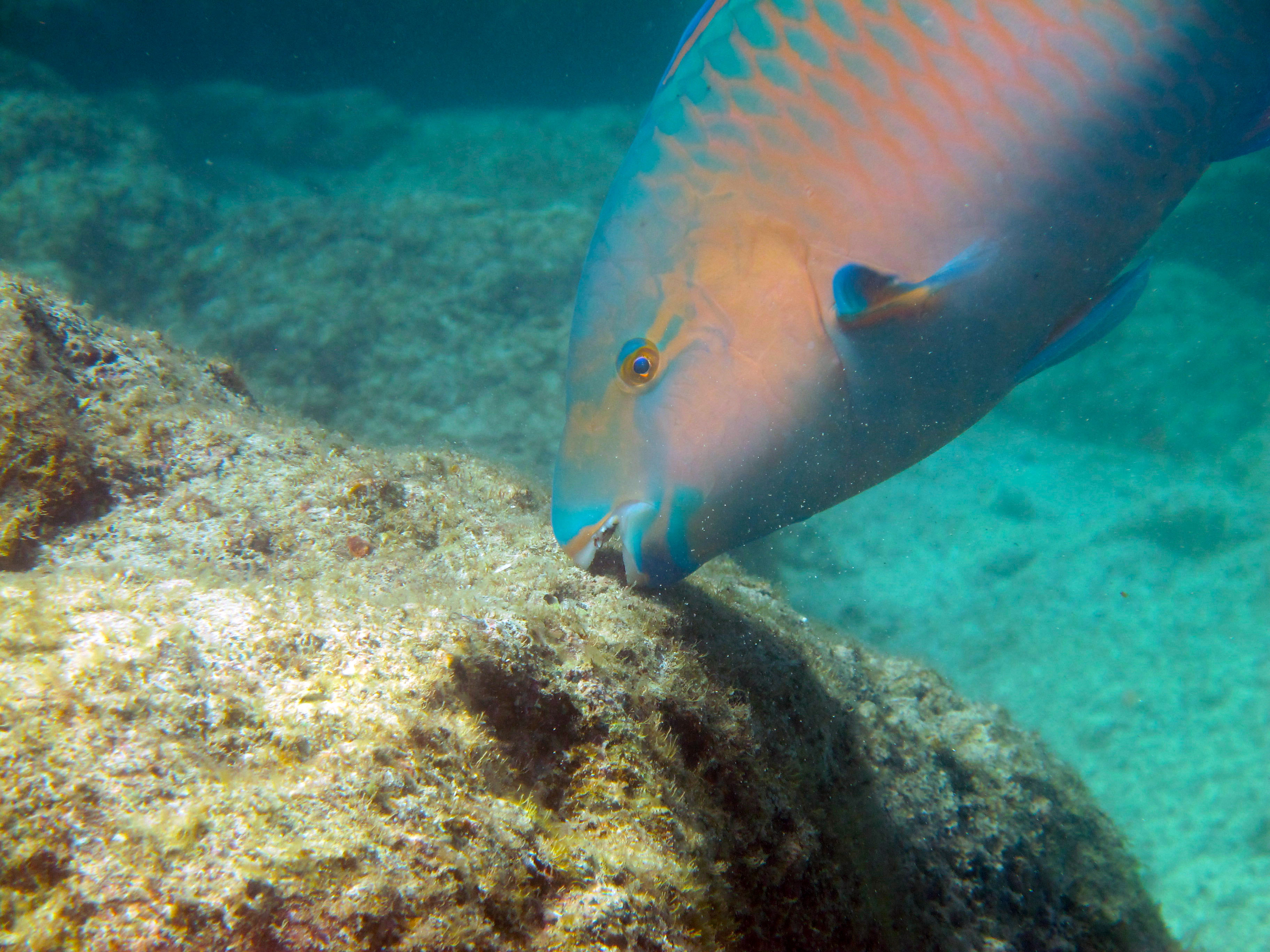

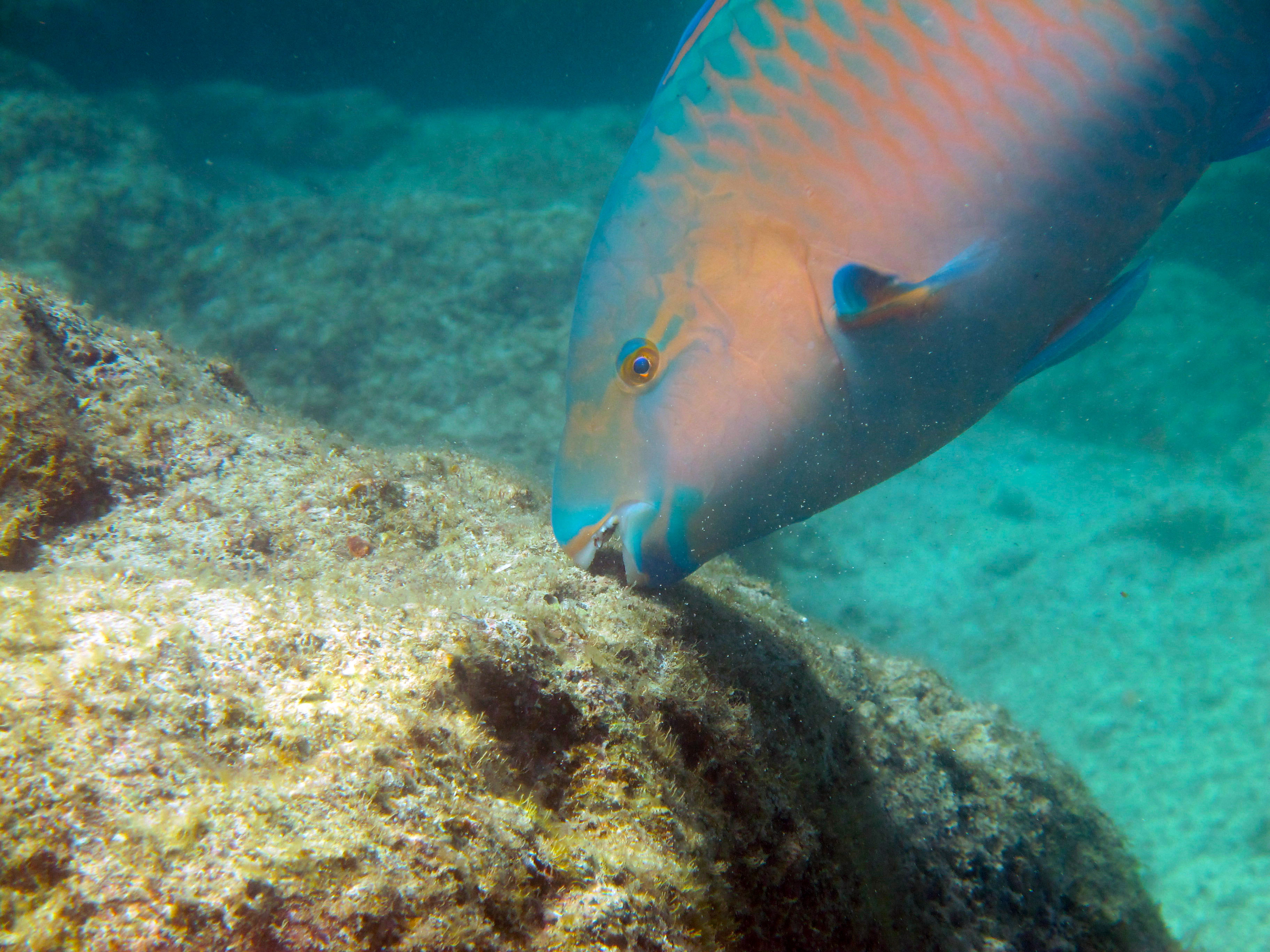

Maybe we'll have to put together a full-on photo post from everyone's photos of the trip, but for now, let's talk science! For my project, I studied the grazing behavior of herbivorous parrotfishes around El Pardito. Parrotfishes inhabit mostly tropical waters and are well-studied on coral reefs, because they graze down algae that can outcompete the reef-building corals - and also sometimes consume the corals themselves. However, their range also extends up into the Gulf of California and other subtropical areas where their role in the ecosystem hasn’t been studied as well. Therefore, for my project, I sought to collect preliminary data on the grazing behavior of these fishes.

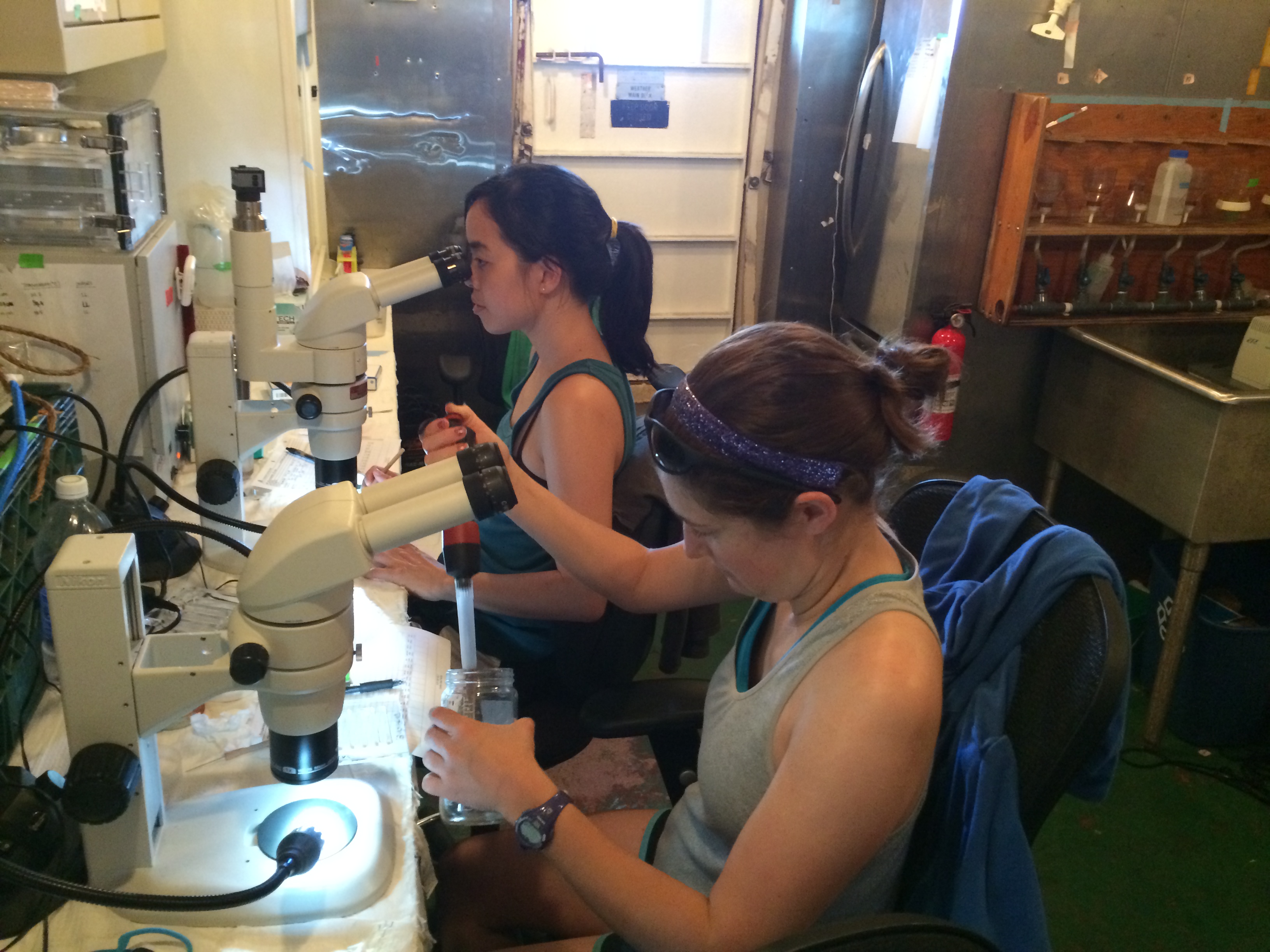

To do so, we (myself and other students/instructors in the course – gotta have dive buddies!) followed individual parrotfish around on SCUBA and recorded what they were biting (e.g., fleshy algae, calcified algae, coral, etc.), how frequently they bit each item, and how big their bite scars were. In addition to feeding behavior, we also noted any interactions with other fish. For example, we noticed that some parrotfish chased one another, with the larger individuals being the aggressors. We did this for almost 200 individual fish, spread across four species (we spent a LOT of time underwater), so we were able to collect some good data! The following are some photos of the four species in question (credit goes to Dr. Scott Hamilton for the great photos!).

Scarus ghobban, the bluechin parrotfish (can you guess how it got that name?), grazing on small, filamentous algae (Photo: Scott Hamilton)

The azure parrotfish, Scarus compressus, another common parrotfish at El Pardito (Photo: Scott Hamilton)

The bumphead parrotfish, Scarus perrico. Kind of goofy-looking, but certainly has charisma! (Photo: Scott Hamilton)

The bicolor parrotfish, Scarus rubroviolaceus, with some small sergeant majors in the foreground (Photo: Scott Hamilton)

Overall, the trip was a big success, as all the students were able to complete awesome projects, and we all gained firsthand experience in conducting field work in a remote setting. Not everything went according to plan, but everyone adapted on the fly and made it work. I know that I'm looking forward to seeing what the next "Baja class" will accomplish!