By Arie Dash, CSUMB Logan Lab

By Arie Dash, CSUMB Logan Lab

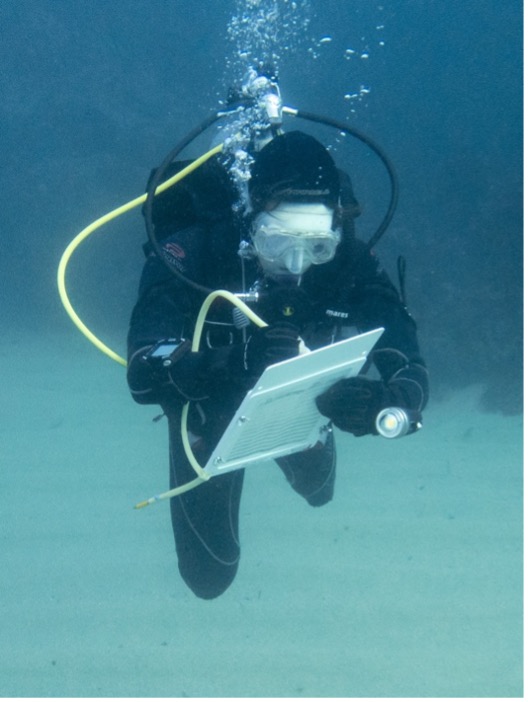

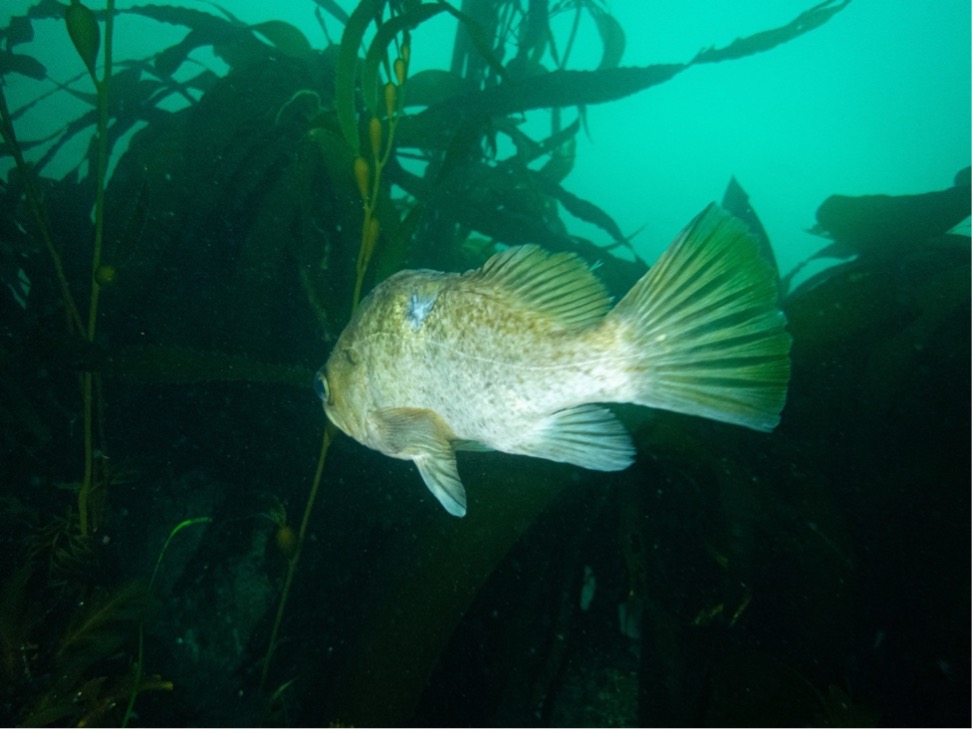

The Logan Lab is the Marine Environmental Physiology Lab at California State University, Monterey Bay (CSUMB). We are a mix of graduate and undergraduate students under the guidance of Dr. Cheryl Logan, and we’re focused on evaluating the physiological responses of marine fish and invertebrates to the current and predicted effects of climate change. Many of our projects rely on analyzing large environmental, physiological, or genomic datasets but most of us do not have formal training in data science.

Over time, we’ve developed several shared workflows, but our code, documentation, and data management practices have not always been optimal. Luckily, this challenge is not unique to our lab and we decided to undertake Openscapes’ 10-week Supercharge plan during the 2020 Fall semester to learn more about current open science best practices. We dedicated a number of our regularly scheduled weekly lab meetings to the Openscapes modules with different combinations of students taking the lead each time.

While we didn’t fully finish the 10-week plan, we made good progress in several areas. At the individual level, most of us started using GitHub to work collaboratively (no more emailing code back and forth!) and started intentionally organizing our files so that others, including our future selves, can more easily use them. We also found that collectively learning about the techniques was helpful when approaching concepts we weren’t familiar with, and as a result, our coding ability has increased tremendously!

As a lab, we wrote a formal code of conduct and created a lab-wide Github page. Most of our sessions were heavily discussion based, which was very helpful for getting everyone up to the same speed and learning about the topics, but we lacked time to actually implement all that we learned. As a result, while many of us made individual progress, most of the lab-wide goals like a shared GitHub page and a formalized onboarding and offboarding process still have work to be done.

In the current 2-month Champions Program, we are excited to learn more advanced techniques for what we’ve already implemented, discuss data management approaches with different CSU labs, and collaboratively implement more open science best practices. This will be an ongoing process, but we hope that by the end of the workshop we will be able to work more efficiently and collaboratively, and that we can further our lab goal of fostering a supportive and inclusive community approach to open science.

By Jason Gonsalves,

By Jason Gonsalves,  By Bri Sotkovsky,

By Bri Sotkovsky,  By

By  By Erick Partida,

By Erick Partida,  By

By  By Kameron Strickland,

By Kameron Strickland,

By Kayla Roy,

By Kayla Roy,