As of Fall 2022 these students in the Vertebrate Ecology Lab have received approval for their Theses Proposals and are now moving into Master's Candidacy

Jack Barkowski

Jack’s thesis work will investigate patterns in humpback whale vocalizations along the U.S. West Coast. Jack will look at the spatiotemporal variation in humpback whale song activity over a 3 year span within the Olympic Coast National Marine Sanctuary, Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary, and the Channel Islands National Marine Sanctuary . He will also report the presence and acoustic characteristics of 5 specific non-song calls that have been documented in humpback whale populations around the world, suggesting that these 5 call types play an important role in social interaction. Jack hopes his work will reveal spatiotemporal differences in peak song activity that will allow for more effective management decisions aimed at reducing entanglement risk in fishing gear and ship strikes from large vessels, the two leading causes of anthropogenic-caused mortality for large whales.

Kali Prescott

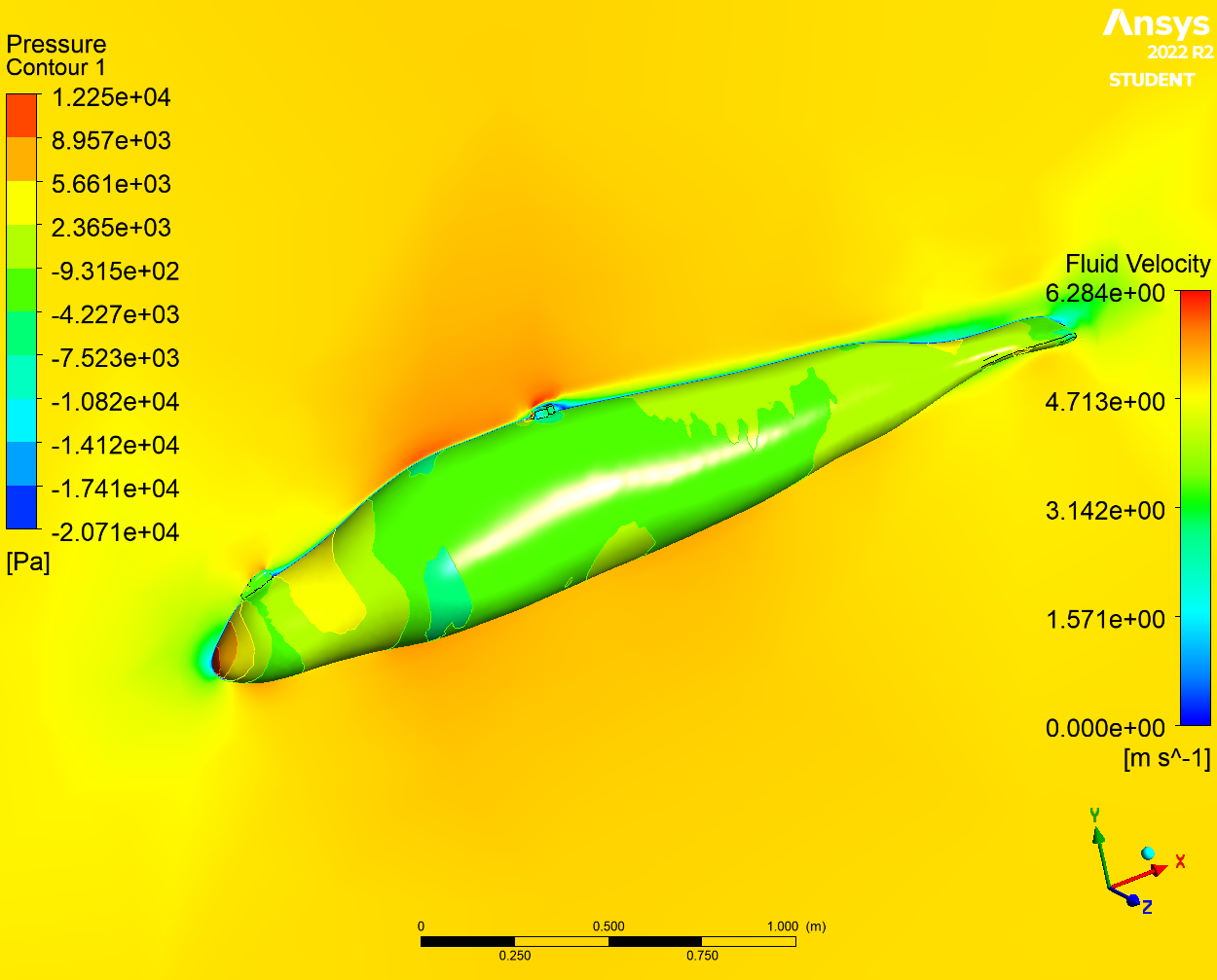

Kali's thesis work will be focusing on exploring how Computational Fluid Dynamics can be used to estimate drag incurred by biologgers and other externally attached devices. She will be examining Northern Elephant Seal, Mirounga angustirostris, as a model species using 3D scans collected during the seal's haul out periods at Año Nuevo State Reserve. These scans will be used to build 3D models of the seals along with 3D models of the biologgers generated using Computer Assisted Design Software (CAD). Using a fluid dynamics program originally designed by Engineers, Kali will simulate drag and drag coefficient by placing the tagged seals models into a computer generated flow through chamber. These models will be used to identify what factors associated with biologger attachment (size, location, and number of loggers) will most impact the incurred drag. These proxies for drag will then be compared to foraging, dive, and reproductive data collected from animals tagged in real life to determine if there are any measurable impacts.