By Hali Rederer, student of California State University Sacramento

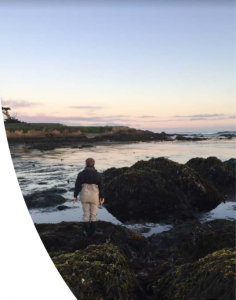

This course broadened my field skills, and enabled me to research rocky intertidal ecology; specifically, tide pool fish. This is a new field of marine fish ecology for me. Designing and carrying out a tide pool fish study, in a very short time frame, in a place I had never been, presented challenges requiring flexibility and creative approaches. Implementing a tide pool fish scientific study was one aspect of my experience. Importantly, and most enriching, was the opportunity to spend time with two university students from Ensenada and getting to know residents of Isla Natividad, and enjoying the food and culture of Baja. We were embraced by the local community and welcomed. A youngster named Lalo helped me collect tide pool data daily and we participated in local holiday celebrations. Facilities were made available to us including a comfortable house, cabins, and a laboratory to work out of.

My fellow students and I were immersed in rich practical “hands on” experiences integrating scientific field methods with experimental design. This course was comprehensive and the pace was fast. Designing and carrying out a tide pool fish study, in a very short time frame, in a place I had never been, presented challenges requiring flexibility and creative approaches. We spent close to eight hours in the field everyday followed by laboratory work and discussions of our projects in the evenings. Topics for specific experiments, laboratory sessions, and discussions derived from our individual research questions, interests, and ideas emerging from our explorations and observations while in the field.

My scientific question: What are the differences between intertidal fish found in higher versus lower tide pool and related tide pool geomorphology?

My research site was a rock strip 400m x 60m. My study accomplished a survey of 30 tide pools for differences in fish abundance, diversity, and distribution patterns in higher versus lower tide pools throughout one MPA rocky intertidal site. I observed and recorded invertebrates, sea grasses, and algae using quadrats. Location, physical features (substrate roughness, water clarity) and physical dimensions of each tide pool were measured. Vertical and horizontal distance from shore was measured to establish the relative position of each tide pool I needed to be constantly aware of tidal influences as the major oceanographic process regulating this tide pool habitat. Integration of physical and biological data stands to capture a more comprehensive picture of Isla Natividad tide pool fish.

The tide pool fish study I had proposed [before departure] needed to change; I had originally planned to capture and measure the weight and length of each fish found in tide pools within one entire site. Turns out that it took too long to capture fish and therefore I adjusted and changed the methods of my study to a visual survey however the overall goal I had of studying tide pool fish remained unchanged.

Position, location, and quality of water in a tide pool is important to intertidal fish, invertebrates, algae, and sea grasses. Near shore coastal marine habitats are vulnerable to anthropomorphic disturbances and influences. Trash is apparent in the MPA site I studied including being found in the tide pools themselves. I roughly measured the debris field and describe its waste stream contents as a second rapid study since residents expressed interest in cleaning up the MPA.

Science as a Collaborative Social Activity

This experience reminded me of how rewarding teamwork in science can be. I was ill to various degrees during the entire trip and was unable to work on my project at all for the first three days on Isla Natividad. Lots of people pitched in to help me complete a tide pool fish study. Field biology works well when there is collaboration and sharing of ideas. I found it comforting when I observed some fish or invertebrate that I thought was different and fellow students or the professors concurred or disagreed and further discussed what might be the most probable explanation. Cheers to my fellow students and a heartfelt thanks to the Professors and teaching assistants. I am eager to apply what I learned on Isla Natividad by sampling tide pool fish in other places along the California current.

What I would come to learn is that this interaction summed up so much of what we the students (and let’s be honest… everyone else as well) love about Kenneth – his ability to teach and explain, without pushing or judging.

What I would come to learn is that this interaction summed up so much of what we the students (and let’s be honest… everyone else as well) love about Kenneth – his ability to teach and explain, without pushing or judging. And now…. Kenneth is retiring. We are looking for a new faculty chemical oceanographer. Candidates have been chosen, interviewed, and evaluated. As students, we are also asked for our evaluations. And as a student, I really don’t feel qualified to evaluate any candidate’s academic merit. The only thing I can evaluate is how any new faculty member might interact with students. Will they understand the grad student struggle? Will they care? Will they make me feel comfortable talking to them about things I might be struggling with?

And now…. Kenneth is retiring. We are looking for a new faculty chemical oceanographer. Candidates have been chosen, interviewed, and evaluated. As students, we are also asked for our evaluations. And as a student, I really don’t feel qualified to evaluate any candidate’s academic merit. The only thing I can evaluate is how any new faculty member might interact with students. Will they understand the grad student struggle? Will they care? Will they make me feel comfortable talking to them about things I might be struggling with?

By Katie Cieri,

By Katie Cieri,

By Kenji Soto, Benthic Ecology Lab

By Kenji Soto, Benthic Ecology Lab