By Jackie Schwartzstein, Vertebrate Ecology Lab

Last weekend, my fellow Vert-Lab-member Angie and I hopped in my little car and made the four hour drive down to Carpinteria, CA for offshore survival training. We are preparing to join a research team that conducts aerial surveys for marine turtles and mammals along the central California coast. Before we can participate in these surveys, we are required to take a course in open water survival.

The M.O.S.T. training course in Carpinteria was designed to give us the tools to survive in the open water when technology fails us, but help is on the way. Courses like this one are increasingly being required for people who work on fishing vessels, oil platforms, and other types of ocean-based employment.

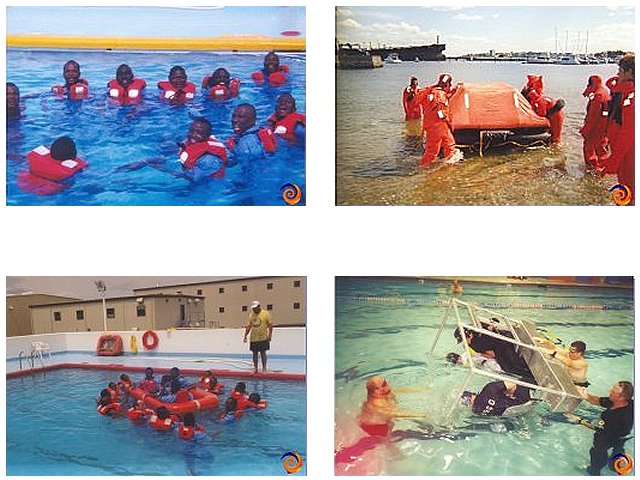

Early Monday morning, Angie and I jumped, fully clothed, into a swimming pool - pursuing safety and preparedness! We started off the day in life jackets, learning how to put them on in the water and even manipulate them while blindfolded. We learned safety swimming patterns to make ourselves larger targets for rescue, to support injured companions, and to defend ourselves from curious or hungry marine life. In an emergency one might not have the chance to even put on a life jacket, so we also practiced making life preservers out of our pants. (This is by far my favorite new party trick.)

After we practiced climbing abord life rafts and familiarizing ourselves with their layout and supplies, we began learning some techniques for surviving a helicopter crash over water. The metal frame in the above picture has seat belts, just like in an airplane. Our job was to strap ourselves into this 'helicopter', get turned upside down underwater, and then calmly un-buckle ourselves and swim out of a designated exit. We did this blindfolded, with skeleton doors and windows attached to the metal frame, and even with a small, handheld tank of air that would extend the amount of time we could remain in the 'helicopter' before surfacing. These tasks may seem strait-forward, but even in a training simulation where there was no real fear of injury I found it difficult to think clearly while upside-down, cold, and underwater. It's a good thing I've had the chance to practice!

We finished off the morning pool training by learning to swim through oil and burning chemicals on the water. By this time we had been in the pool for about four hours, and we were COLD! We were happy to go inside for the remaining classroom-learning portion of the course. Angie and I drove back home Monday night, exhausted, but equipped with a completely new set of survival techniques. Now we just have to make sure that we never have to use them!

Hope everyone is having a relaxing and safe Spring Break!

All photo credit to M.O.S.T. http://www.mcmillanoffshore.com/pictures.htm