by Angela Szesciorka, Vertebrate Ecology Lab

A few Sundays ago — Super Bowl Sunday, in fact — I took a three-hour walk along the beach at Fort Ord in Monterey, CA with Don Glasco, a systems engineer and former cartographer.

This wasn’t a leisurely pursuit, but my volunteer service to the Sanctuary Integrated Monitoring Network’s (SIMoN) Coastal Ocean Mammal and Bird Education and Research Surveys, also known as Beach COMBERS.

I meet Don at Fort Ord Dunes State Park in Marina around 9 a.m. After downing the last of my coffee, we head out into the foggy morning.

We walk along the beach performing a simple line transect survey, that is scanning the beach from the waterline up, looking for beach cast animals — birds, seal sea lions, dolphins. Maybe even a whale, but I hope not.

I get lucky and spot the first bird carcass. I even correctly identify it as a Northern Fulmar – the dark morph. Not bad! I was given the lucky task of clipping one of the toes off with shears. If the bird remains on the beach, clipped toes will inform next month’s team to not double count it.

We find five northern fulmars, two common murres, two grebes, two Brandt's cormorant, and the neck from some unfortunate, unidentified bird.

Don is an ARMY brat like me, so we bond over similar childhoods. We talk about California, the military, Fort Ord. He tells me about Stillwel Hall, the dance hall that used to sit at the waters’ edge at Fort Ord. Paid for with “voluntary” soldier contributions in 1943, the hall hosted big band names like Duke Ellington, Count Basie, Elvis, Bing Crosby, and Bob Hope. Who would have known!

Don is an expert birder. He knows every terrestrial and marine species, in California at least. I quiz him – killdeer, surf scoter, sanderlings. He knows them all.

We continue our walk. Most of the birds we find are in various states of decay and scavenge. One pair of wings and feathers everywhere makes me think it met an ornery stray cat.

I look ahead to see a monstrous turkey vulture staring right at me. I quickly realize that it is perched atop large dark mass. Imagine my surprise when I find it’s an adult male California sea lion carcass! The turkey vulture resentfully leaves so we can take measurements and mark the flipper with twine.

Three exhausting hours later we’ve walked 5.36 km, and I’m ready for a nap. We’ve documented a plethora of data, including species, state of decomposition, age, sex, evidence of scavenging and oil, and potential cause of death — although cause of death can never really be determined in the field.

The data will be compiled and later used by the BeachCOMBERS scientists to monitor trends in mortality, biogeography, abundance, diversity, migration patterns, and human impacts.

Beach COMBERS was started in 1997 by Scott Benson, a former MLML student who is now at the Southwest Fisheries Science Center. The main goals of BeachCOMBERS are to obtain baseline information on deposition rates of marine birds and mammals and assess the causes of seabird and marine mammal mortality.

The program is really a collaboration between Moss Landing Marine Laboratories and Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary, along with other state and research institutions including the California Department of Fish and Game, the Marine Wildlife Veterinary Care and Research Center, and the University of California Davis.

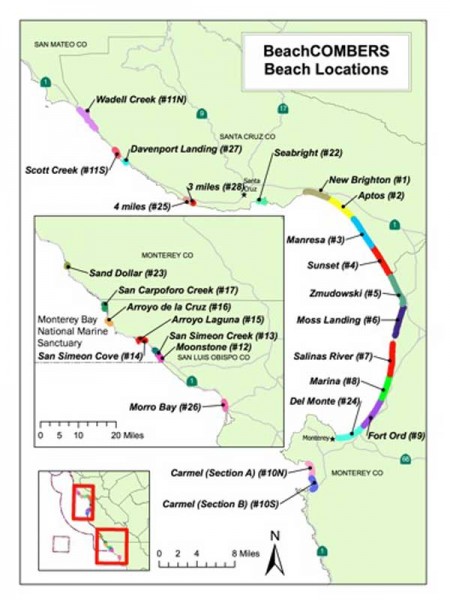

Since its inception Beach COMBERS has had more than 190 volunteers. Current volunteers survey 79 km of the Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary beaches each month.

The data these volunteers have collected are yielding results. A number of unusual mortality events have been uncovered and attributed to changes in environmental conditions — nine to oiling, three to harmful algal blooms, three to population increases, two to fishery interactions, one to natural predation, and one to unknown circumstances. Seabirds are the most abundant animals encountered during beach surveys. California sea lions are the most commonly encountered marine mammal.

The 1997-2004 report can be found here.

If searching for and playing with marine carcasses sounds fun to you (it is!), I recommend you consider volunteering. It's only a once a month commitment for roughly two to four hours of work and you get to go to the beach!

And no, this is not what I mean when I say beach combing. (Classic though.)