By Diane Wyse, Physical Oceanography Lab

Earlier this week I volunteered to dive on the MLML seawater intakes, located about 200 m due west of the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute (MBARI) and 17 m below the surface. The intakes supply seawater to multiple sites around Moss Landing, including the aquarium room at MLML, the Test Tank at MBARI, and the live tanks at Phil’s Fish Market.

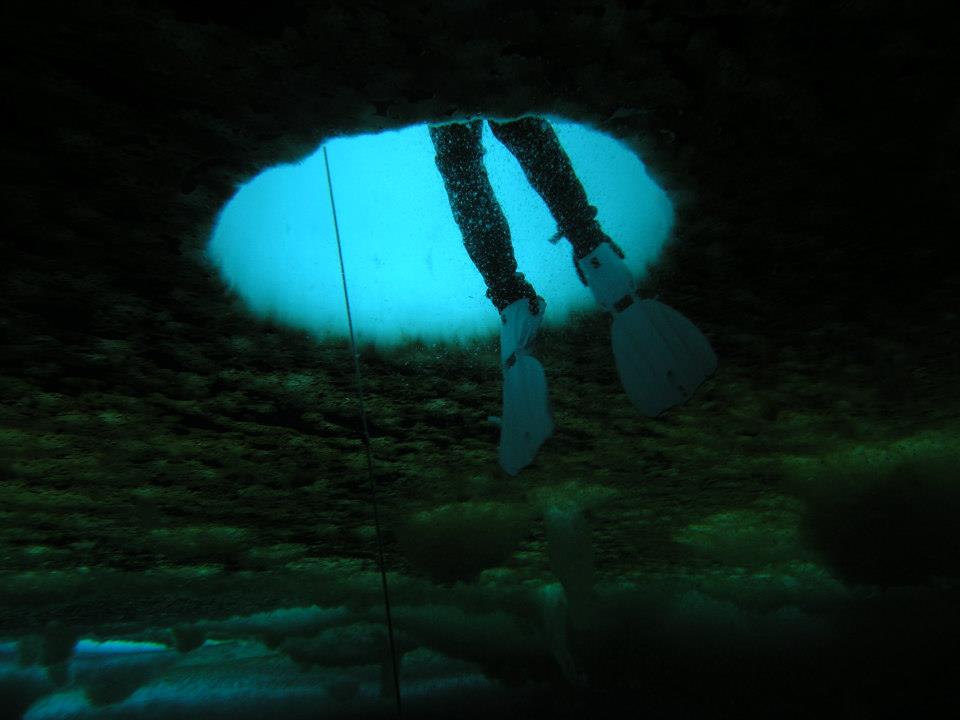

The purpose of the dive was to attach a surface float to a subsurface float located at a depth of about 15 feet. A secondary objective was to visually inspect the intakes, which can be viewed in the video below.

So how do you find an intake system 50 ft below the water?

To execute the operation, Assistant Dive Safety Officer Scott Gabara and I took a whaler from the MLML Small Boats with the assistance of boat driver Catherine Drake. We used the best GPS coordinates previously called upon to locate the intakes, then threw a spotter surface float attached to a line and weight that unraveled to the seafloor. We followed that line to the bottom and practiced our circle search skills until we found the first of the two intakes. While anchoring the search line I saw a pipefish, a couple flatfish, and not much else. During our descent and ascent we spotted half a dozen sea nettles, but on the sandy bottom it appeared pretty desolate. The intakes, on the other hand, provide a hard substrate for sessile invertebrates and their predators to form a lively little oasis in the sand. The first thing you notice when you come upon the intakes are the large white Metridium anemones. If you take a closer look at the video, around 15 seconds in, you can spot a little octopus scurrying for cover. After inspecting the first intake we moved to the second, that’s right, completely submerged by sand, with the line extending up to the subsurface float. Though the video is short you can see some of the organisms residing on the line include seastars, Metridium, caprellids or “skeleton shrimp”, and my favorite marine invertebrate: nudibranchs. Hermissenda (opalescent) nudibranchs, to be exact. I wish I had a chance to take still photos while I was out there, but we had a job to do. We successfully tied the surface float to the line and removed old line, thus making it much easier for future divers to study sediment movement and perform maintenance on the intake pipes.

I'll admit had another motivation for volunteering for the dive. Beyond helping out and increasing my scientific diving experience, I was curious about the system. In 2011 and 2012 I worked as a research assistant for CeNCOOS, and helped maintain the oceanographic instruments at the MLML shore lab and ensure that the public data portal was operational. That system is dependent upon water flowing in from the intakes. I learned even more about the seawater system in my chemical oceanography class, so it was really cool to see the pipes from under the sea. The visibility for most of the dive was much better than it seems in this video, as we spent most of the time working further up in the water column away from the fluffy layer composed of detritus and fine-grain sand.

When my dive buddy and I returned to the surface we met back up with our boat, reeled in the line for the first float, and cruised back to the harbor. Another day, another successful dive!