Given that we had no internet and limited power at Cape Crozier for 4 weeks, we’re going to give a short and sweet, highlight filled recap because we were too busy to write a weekly blog.

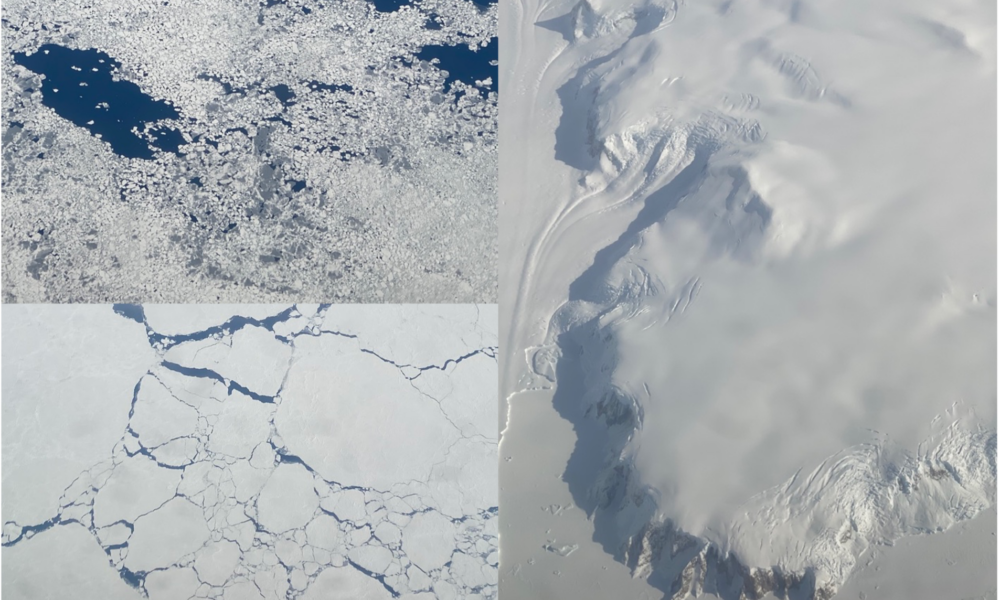

Twinkling air crystals

On day one, 5 helicopter flights from Scott Base took our team, all our gear, and some support personnel out to help us set up camp. With help we got all our tents up and secured to the sea ice (using a fancy drill to create rope anchors into the ice called v-threads) in one day. We dug our sleeping tents into the snow to protect it from the wind and one of the most spectacular things about the whole day was watching suspended ice crystals sparkling in the air as we set up camp. At first, I thought I was having a stroke and nearly panicked, but once I realized other people were seeing it too, my panic turned into pure wonder and delight. I can only guess that the snow-shoveling mixed with winds from the helicopter must have stirred up the enchanting sight. But maybe there is another more scientific explanation, or perhaps it was just pure magic.

300,000 Adelie penguins

Yes, we were there to study emperor penguins, BUT… one of the most impressive things about Cape Crozier is the 300,000 Adelie penguins breeding on the side of Ross Island just opposite our field camp on the sea ice. You could hear the cacophonous humming of their mating calls from camp and see a whole hillside covered in guano and little black and white penguin specks. The first few days in camp we had a field trainer with us that was there to ensure we were set up for safety and success and he took us on an amazing and terrifying (to me, the novice) adventure across the sea ice to Ross Island. The point of the mission was to show us how to safely move across the sea ice transition zone onto land should there be any sort of emergency (like the sea ice starting to break out). We were shown how to drill into the sea ice to test its depth and what depths could be safely traversed (we had to go across some big cracks that thinned quite a bit at the middle). Once we got to the more jagged ice, we heard a Weddell Seal calling beneath us and saw it breathe, spraying icy water up into the air. It was amusing watching our (actually very brave) field trainer startle and jump off the chunk of ice before he realized it was the sound of a seal and not the sound of capsizing ice. As impressive as it was to finally get up close and personal with so many nesting penguins, I still think they are most entertaining while running across the sea ice – every so often, one slips or trips while crossing an ice crack, then turns around to examine the offending ice very crossly raising the feathers atop their head. They have the best, sassiest personalities and remind you of it every time they pass by with a loud grumbling squawk to let you know they are *not* happy to see you. I love a sassy bird!

The sovereign rulers of the ice

Of approximately 2,000 emperor penguins lumbering about the ice, we caught and put fancy little devices on 32 penguins. A large portion of our subjects were affixed (using a combo of tape and a touch of glue on the feathers) with Axytrek devices which measured where they went via GPS, how deep they dove with a pressure sensor, and how they moved in 3-dimensions with accelerometer. A smaller portion got affixed with satellite tags that would transmit location and diving data to a satellite that we could later download, and thus not have to retrieve the device from the bird. These tags are still transmitting and that’s how we plan to find where the penguins have gone to molt and renew their feathers (thus depositing the device with the discarded feathers onto whatever ice floe they’ve decided was sufficient for their month-long molt process).

The emperor penguins are obviously the main attraction and were the pinnacle of our trip to Crozier, not just because of the science we accomplished, but because they are one of the most remarkable birds in the world. Not only are they big (almost 60 lbs!) and stunningly beautiful (I mean, just look at them!), but they are incredible athletes. One of our penguins dove to over 500 meters! On average, penguins spent 9 days at sea foraging for their chicks. And don’t even get me started on how cute the fluffy chicks are. These little guys and gals spend their days flopped over on the ice (sometimes eating snow) or running around the ice flapping their flippers like little pool noodles, squawking and begging for food, and filling their little jelly pot bellies when mom or dad comes home to feed them. Oh, and pooping. There is lots of pooping! It’s not all glamor with this lot of royalty; only a fresh coating of snow can hide that fact. The penguins love a coating of snow too – they roll around in it like puppies and love to “toboggan” on it – saving themselves from the endless grind of shuffling across the sea ice one footstep at a time. The only downside, as far as I could tell, is during the blizzards, when the little fluffs of down feathers get caked in snow – doesn’t look all that comfortable, at least not to us humans. But thankfully, these incredible birds are well adapted to extreme cold.

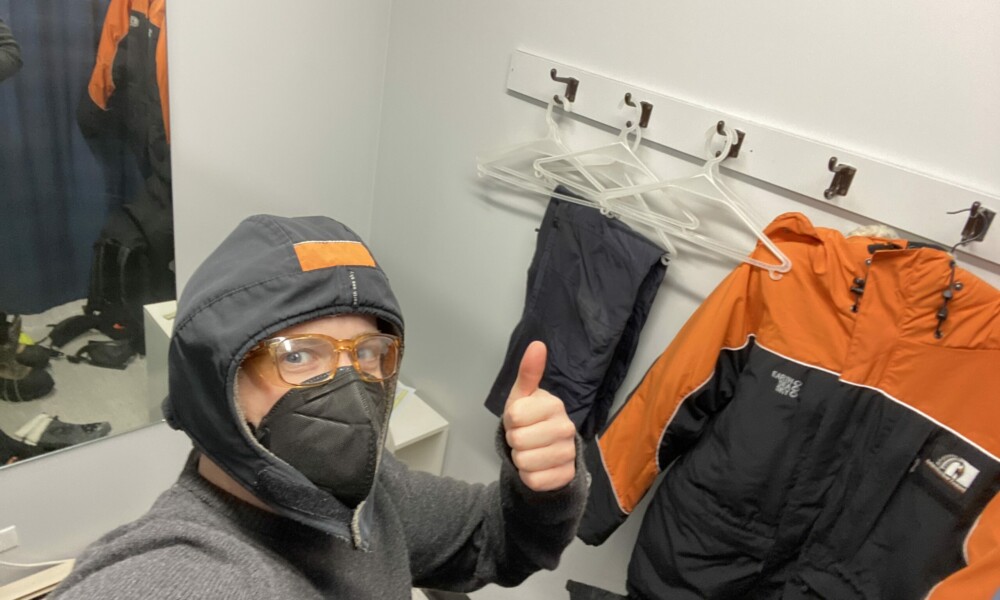

Camp life – typical daily tasks

- Wake up, and scan for birds that may have come home from foraging with Axytrek devices. Each bird also has a radio transmitter that we can pick up with a radio receiver to hear a distinct beeping when the bird has returned to the colony.

- Continue scanning every 45 minutes.

- If lucky, go catch a bird!

- Download tag data, process samples, enter data, process data

- Eating, lots of eating – when you’re cold you have to eat a LOT!

- Hydration – as the saying down there goes “hydrate or die!”

- Cut snow blocks for wind protection for camp and to melt for water

- Filter dirt and krill and guano bits out of the melted water

- Refuel the generator and charge up the batteries

- Check the stove fuel and make sure the polar haven stays warm

- Check all ropes outside to make sure everything is secure in case of a storm

- Check the growing sea ice crack leading up to camp (at some point, a seal popped out of this!)

- Radio safety checks to Scott Base (they were very good at giving us daily jokes to keep us entertained)

Photo Credit: Caitlin Kroeger