Jess Franks, Phycology Lab

Food has a remarkable ability to unite people, bridging social tensions and fulfilling communal desires. For some, it’s a basic necessity; for others, a delightful indulgence. At home, meals often follow a predictable routine, offering comfort and meeting expectations. You know whose turn it is to cook dinner, who’s on dish duty; and when you’re not in the mood for cooking, there’s always the option to order takeout. As someone who appreciates the art of cooking, and tends to indulge when it comes to food, traveling always presents unique culinary opportunities.

Our class trip to El Pardito added an extra layer of complexity to meal planning. Questions arose: What would we eat, considering everyone’s dietary needs? Who would take charge in the kitchen? And perhaps more crucially, who would do the dishes? These decisions needed to be made for every meal.

Unlike my usual routine of coffee for breakfast and leftovers for lunch, our journey demanded a different approach. To capture the reality of our food journey, I diligently recorded our culinary delights in my notebook. On road trip days, we ate tacos for lunch—the first day in Ensenada with Alison Haupt, and the second day we had fried fish tacos on the way down to Guerrero Negro. We (Scott) liked that taco stand so much that we stopped there again on the road trip back up the peninsula. Our first dinner was at Gonzo in Carlsbad, CA, featuring spectacular ramen—a much needed energy boost after a full day on the road. Crossing into Mexico, our first homemade dinner of burritos was prepared in the parking lot of the only hotel in Guerrero Negro with vacancies on Easter weekend.

On El Pardito, dinner was prepared by Sofia y Simon, supplemented with a salad prepared by whoever was on food group that day. Sofia y Simon, a kind and welcoming couple residing on the island, welcomed our attempts at Spanish, told us stories of their past, and facilitated our communal meals with their beautiful palapa and culinary abilities.

Every night unfolded with a familiar rhythm: the food group gathering an hour before dinner to prepare the salad, Simon and Sofia guiding us through meal prep—often involving warming tortillas or crafting tofu and chickpea dishes for our vegetarian friends. Once the culinary stage was set, we meticulously arranged the dining area underneath the palapa, playing with the feng shui of the tables on several occasions. Finally, Simon rings the bell, everyone else climbs the stairs to the palapa, and Simon brings out dinner.

Each evening’s menu boasted comforting staples like arroz y frijoles, ensuring solid digestive movements, and fresh fish caught by the island’s fisherman. One standout dish that left a lasting impression was the yellowtail (“Jurel”) sashimi. The tale of its catch—a spontaneous fishing excursion by Michael resulting in a bountiful catch—added a delightful twist to our culinary adventures. Drizzled with lime, jalapeno, and red onion, the sashimi became an instant favorite, feeding ~20 of us and offering leftovers the next day.

Mealtime wasn’t just about nourishment; it was our daily rendezvous for sharing stories, exchanging laughter, and reflecting on our day’s escapades. Our tradition of sharing the “Favorite/Coolest thing you saw today” allowed each of us to relive special moments, fostering deeper connections amidst shared experiences. These conversations seamlessly transitioned into planning our next day’s adventures and coordinating logistics—a testament to our collective endeavor and collaborative mindset.

As the evening wound down, we embraced the less glamorous yet essential task of dishwashing. While the food group bore the primary responsibility, the communal spirit often prompted others to lend a hand, reinforcing our ethos of mutual support and teamwork.

This nightly ritual, spanning about 3 hours, wasn’t a mundane chore to us. It encapsulated the heart of our journey—a time of togetherness, shared responsibilities, and the bonds that grew stronger with each passing meal. In retrospect, my favorite part of the day was the simple act of sharing meals.

By Acy Wood,

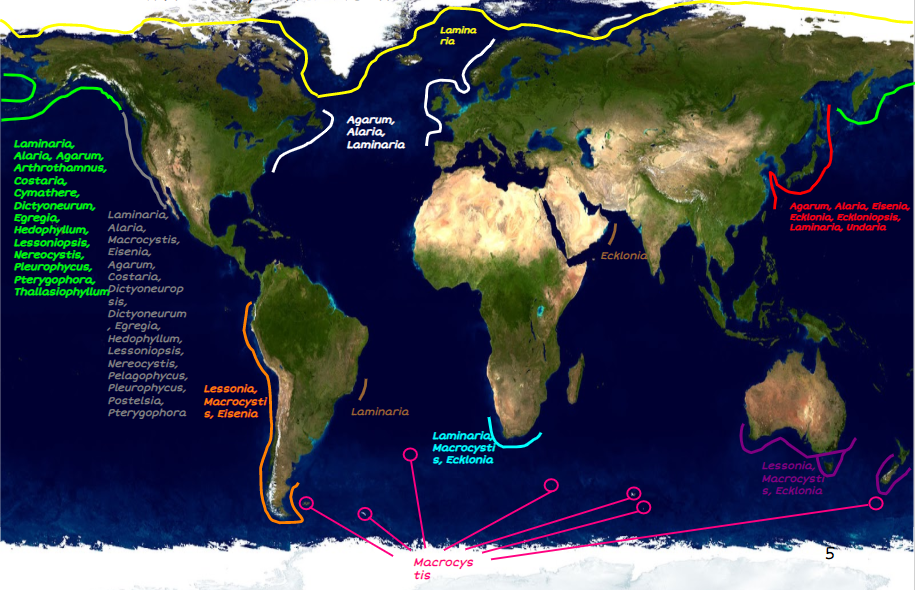

By Acy Wood,  The reliance on a single species means that researchers need to give special attention to the conditions that species thrives in. Any changes that the foundation species experiences will inevitably trickle down to the other community members. Going back to our example, if the kelp that make the kelp forest are unable to thrive, then the young rockfish will have to go somewhere else to hide. Oftentimes, underwater plants are sensitive to specific temperatures or specific depths. They may grow very well in places that have the right mix of conditions, but will no longer flourish if those conditions happen to change from what the plants need. Similarly, if an area nearby changes to suit them, then they can move right in.

The reliance on a single species means that researchers need to give special attention to the conditions that species thrives in. Any changes that the foundation species experiences will inevitably trickle down to the other community members. Going back to our example, if the kelp that make the kelp forest are unable to thrive, then the young rockfish will have to go somewhere else to hide. Oftentimes, underwater plants are sensitive to specific temperatures or specific depths. They may grow very well in places that have the right mix of conditions, but will no longer flourish if those conditions happen to change from what the plants need. Similarly, if an area nearby changes to suit them, then they can move right in. By

By

This post is a companion to the recent post about the Global Kelp Systems course. While both Chile and Monterey are dominated by kelp, they are not identical. Part of the fun of the class was the ability to compare and contrast the local environments.

This post is a companion to the recent post about the Global Kelp Systems course. While both Chile and Monterey are dominated by kelp, they are not identical. Part of the fun of the class was the ability to compare and contrast the local environments.