by Erin Loury, Ichthyology Lab

Your mission, should you choose to accept it: describe a new species unknown to science. That’s exactly the mission a few MLML students undertook last spring in a class on systematics. Systematics is the study of how all living things on earth are related to each other through evolutionary relationships. It involves figuring out how species are grouped together in these relationships, and identifying what makes species different from one another – a lot like a detective piecing clues together.

Ichthyology student Kelsey James recently cracked the case of of the Eastern Pacific black ghost shark. This fish is a new species of chimaera, which is a cartilaginous fish related to sharks and rays. Although scientists collected a specimen in Baja California in the 1970s and thought it was a new species, the fish languished in a jar for years waiting for someone to take the time to investigate it (a story all too sad and true for many new species out there). After Kelsey’s close examination, she and other scientists decided it was indeed different from other chimaeras, and gave it the scientific name Hydrolagus melanophasma in a recent publication.

According to Kelsey, the process of describing a new species is actually fairly straight forward. “First you have to look at everything closely related to it in the same genus, and then decide why it is or isn’t an already described species,” she said. Sometimes it’s easy to see that a species looks different from others, but describing why it’s different in terms of body measurements (like fin size and spacing, jaw length, etc.) can be much harder to explain. “The hardest part for me was describing a few good key characteristics that anyone could use to identify this species, which is called a diagnosis,” she said

[youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jelQFJ0u7TA]

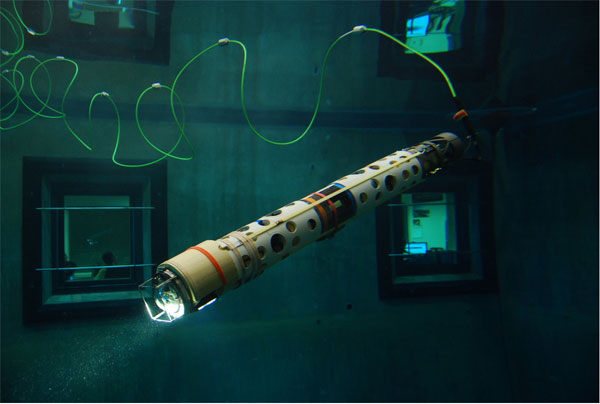

What made the project particularly exciting for Kelsey was that MBARI (the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute) had ROV footage of her species swimming around at 1500 m in the Gulf of California (video above). “It is spectacular to see this creature in action,” she said after watching their tapes. “The differences between the preserved specimen, which I had been looking at for 2 months, and the live one were astounding.”

In addition to being published in the scientific journal Zootaxa, the story has created a lot of media buzz, garnering press time from the Smithsonian, Wired Science, National Geographic, and even a German website. Not bad for a class project!