By Jamie Sibley Yin

Dr. Valerie Loeb is an adjunct professor at Moss Landing Marine Labs. Currently, she functions as an independent Antarctic ecosystem research scientist collaborating with Jarrod Santora of UC Santa Cruz. In April, she headed out to sea with a new NSF funded project entitled "Pilot Study: Addition of Biological Sampling to Drake Passage Transits of the 'LM Gould'". The following are updates from the field by Jamie Sibley Yin who is in charge of communications.

April 19th, 2015 - Palmer Station and Ice Fish Project

When I woke up it was hard to believe we were in the same ocean as last night. The water was glassy and glaciers cut with snow-capped black rock towered on either side of us. We were due at Palmer Station in less than an hour. Palmer was the final destination for some folks—but not us. We were going with the ship, wherever she went.

This meant fishing in Gerlache Strait and recovering underwater gliders from Shackleton Ridge.

Palmer far exceeded my expectations for a station on an island off the coast of Antarctica. It’s nestled between light blue glaciers and looks out to the rock-studded ocean. The station feels like a ski cabin, fire roaring in thewood stove and floor to ceiling glass windows. The facilities are excellent and include a sauna and outdoor hot tub. After lunch we walked up the glacier behind the station (think gentle sloping glacier—nothing hard core). We take a radio and write our estimated time of arrival on the board. If you are not back by this time, the rescue team at Palmer must spring into action and come find you. The Antarctic landscape is harsh and far from any medical facilities, thus, every precaution is taken to prevent and minimize injuries.

After our glacier jaunt, dinner was served at the station, everyone from the ship was invited to dine with the station dwellers. All was merry and the food was spectacular: tacos with chile verde, seared fish, heaping bowls of guacamole and honeydew relish. Who knew food could be so wonderful in Antarctica.

I was a bit sad to leave station after basking in its’ glory for only two days, but to sea again it was. This leg of the journey was for the icefish group to catch their fish. They are studying two groups of fish: Nototheniods, an endemic group of Antarctic fish, and Channichthids, also known as icefish. Icefish are unique in that they don’t have hemoglobin, a vital oxygen-binding protein found in the blood of all vertebrates. Their blood is therefore milky white. They are studying the thermo-tolerances of these fish and how they will respond to warmer water temperatures, potentially modeling their response to climate change.

They have a lab set up at the station but first they must find their fish. They use pot traps and benthic trawls to fish. The boat goes to specific locations where they have had success catching their fish in previous years. The trawling areas must have sandy bottoms (so the net doesn’t become snagged on underwater pinnacles). The pots are deployed in strings of four. They are left out for 24 hours after which we retrieve them and the fish inside. The icefish are strange-looking creatures, with flat elegant mouths and large sentient eyes they look more like crocodiles than fish.

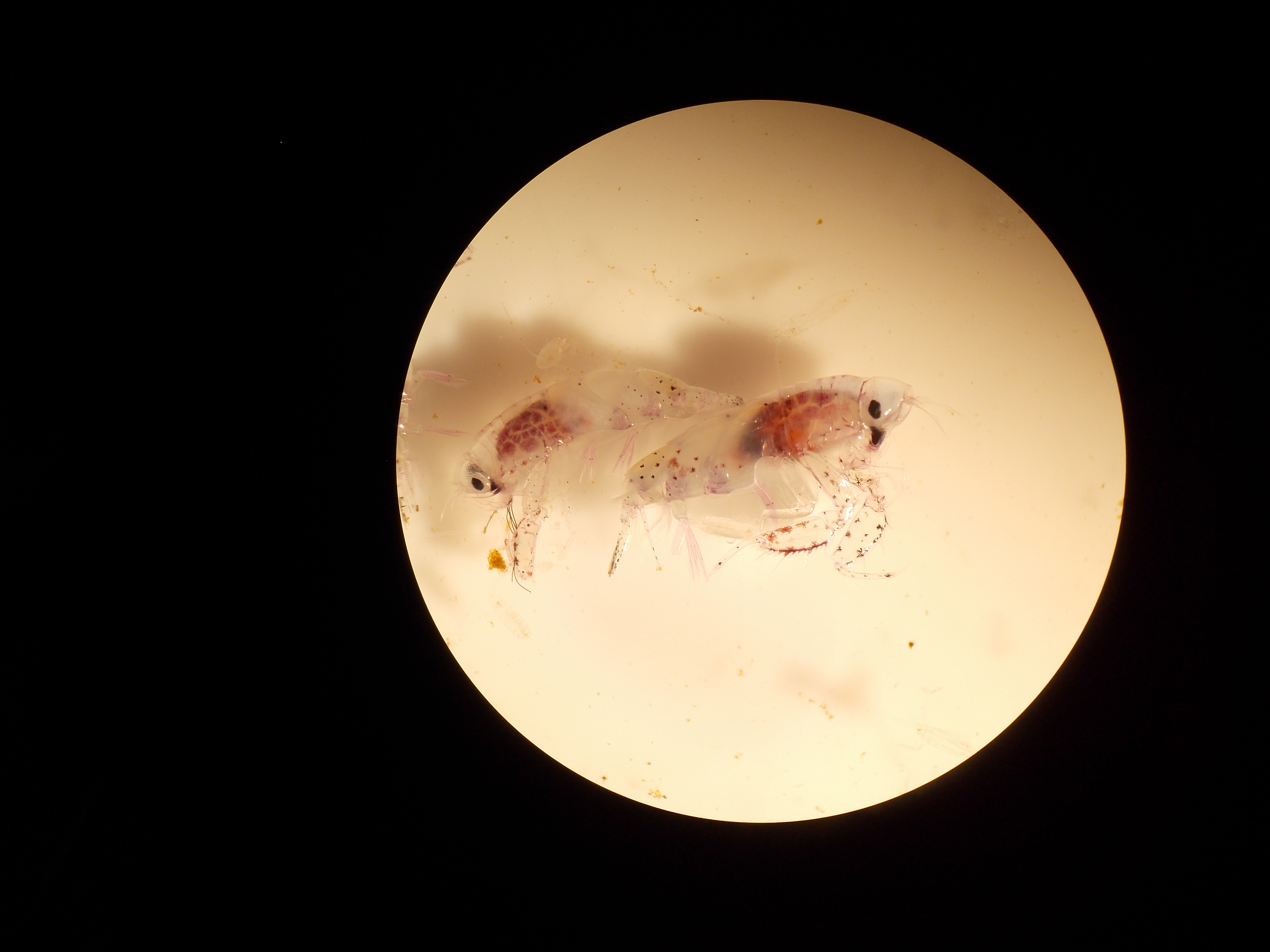

Our zooplankton sampling has been put on hold until the fish crew is done. We are still sorting through our samples and attempting to identify all our critters, including some very small copepods that are barely a few millimeters in length. It will be interesting to see how their composition changes when we sample closer to the continent.