by Parker Forman, MLML Vertebrate Ecology Lab

by Parker Forman, MLML Vertebrate Ecology Lab

Transcript of radio chatter from the penguin scientists at Camp Crozier 13:15 hrs on November 15th 2019:

Markus: Gitte and Parker ....... This is Markus ....... Do you copy?

Gitte: This is Gitte and Parker ........ We copy .......... Over

Markus: Penguin 5 has returned to the colony! ....... David and I have eyes on ....... Penguin 5 ......... Over

Gitte: Markus ........ We will meet you at the colony ........ Clear

In Pursuit of Penguin 5

This is the moment we have all been working so hard for, years of planning and preparation, penguin 5 has returned after spending 17 days at-sea foraging for its chick. Gitte and I quickly put on our jackets, extreme weather boots and ice crampons, grab our field gear and head out of the research tent to meet up with Markus and David at the emperor penguin colony. The colony is a quick 20 minute walk from our camp but the strong northerly wind slow our progress as we make our way across the sea-ice. At the halfway point to the colony, we carefully cross two major cracks in the ice that continue to grow in length every few hours. The condition of the ice in this area is essential to our daily commute as it is the only spot we can safely access the penguin colony from our camp. The ice crossing is one of my favorite parts of the walk as I can often hear the alien like rumble and ticks of nearby Weddell Seals and on occasion I can see them breath at the surface of their ice holes before they disappear below the ice. As we cross the “main crack” a section of sea-ice that continues to separate by close to one meter (~3.28 ft) per day, Gitte and I continue to follow our previously flagged route and can see the trail of emperor penguins in the distance coming and going from the colony.

Photo Credit: RNZ / Alison Ballance

Looking north we can see thousands of Adélie penguins elegantly dancing across the slick ice upon their return to Ross Island which is quite a long hike for this mighty little penguin. At times like these, I often pinch myself to check if I am dreaming and redirect my attention away from the real world Happy Feet like scenario that constantly surrounds me. Quickly, I am back to the task at hand, finding penguin 5. Gitte and I arrive at the Cape Crozier colony and see our fellow researchers (Markus and David) with their binoculars pointed in the direction of a small group of emperor penguins near the outskirts of the colony. As Gitte and I get closer to the colony, she is quick to locate penguin 5 wearing a biologging tag on its back. At this moment I am sure our research crew is all thinking the same thing, “I wonder where that penguin has been, how deep did it dive while on its journey, and did our biologger successfully document any of this information?” At last penguin 5 has returned from its long trip at-sea but our work here is far from over.

Meet the Penguin Team

My name is Parker Forman and I am a graduate student in the Vertebrate Ecology Lab at Moss Landing Marine Laboratories (MLML). For my master’s thesis, I am studying the at-sea behavior of emperor penguins at Cape Crozier. In late October I had the incredible opportunity to go to Antarctica to collect data for an international collaborative effort between NIWA researchers in New Zealand and MLML to document the at-sea behavior of chick rearing emperor penguins at their most southern location on the Ross Sea, Cape Crozier. This research was not possible without funding from the Ross Sea Research and Monitoring Programme run by NIWA, and the additional support that covered travel costs and field gear from National Geographic and SeaWorld. As a part of a four person team, including our leader Dr. Birgitte McDonald (my advisor), Dr. David Thompson (avian ecologist from NIWA) and Dr. Markus Horning (researcher from the Alaska SeaLife Center and sleeper shark expert), we packed our field gear and flew down to Antarctica to camp on the ice, to live among and study the emperor penguins at Cape Crozier.

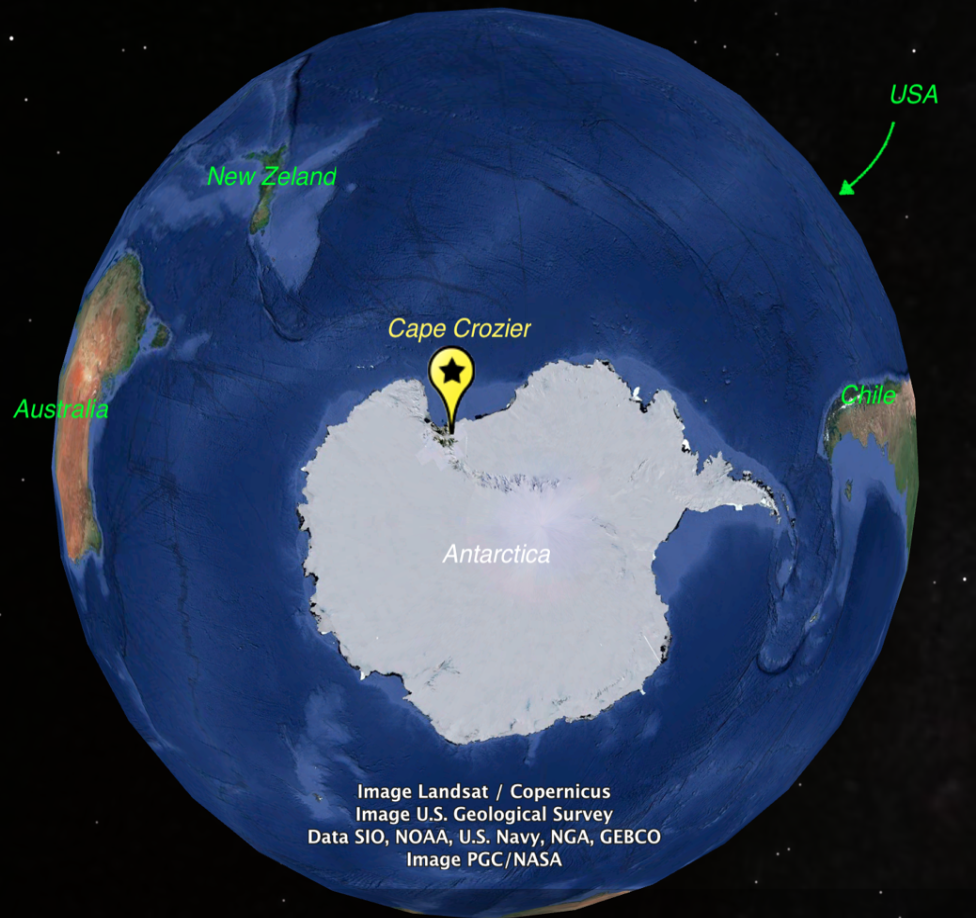

Holdup....Where is Cape Crozier?

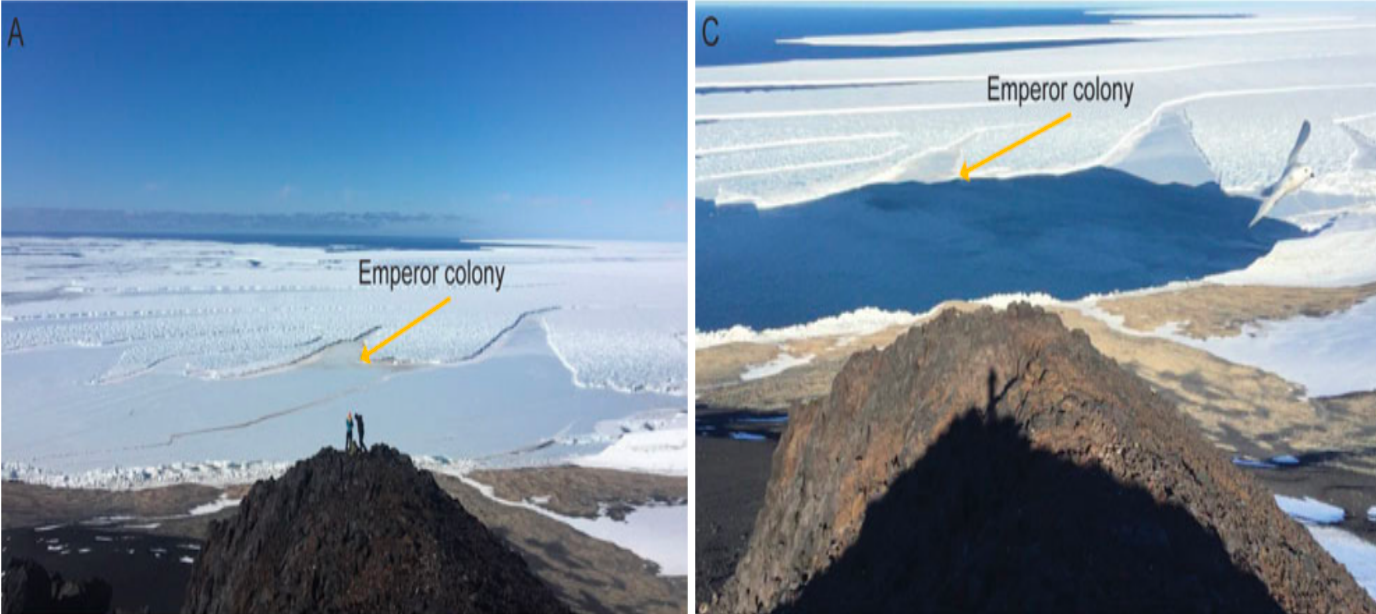

This research took place at Cape Crozier, which is located on the Ross Sea (Image 2). The research was based out of Scott Base, the New Zealand operated field station. At Scott Base, we prepared our field gear into five helicopter loads and flew to Cape Crozier (a quick 35 minute flight), where we camped on the sea-ice for four weeks. For the duration of the expedition we lived in tents that were fastened to the ice (Image 3). All of our water needs came from melting snow that had to first be filtered from the adélie guano blown from the nearby colony on Ross Island. Below is a picture of what our camp setup looked like as documented by Radio New Zealand’s Alison Ballance (Image 3). The big blue structure in the background was our research tent that had one of our most essential tools, a running stove to keep us and our science equipment from freezing. From our camp, we were a short 20 minute walk on sea-ice to the penguin colony.

Let’s Talk About Penguins

Emperor penguins are the largest of the penguin species measuring close to four feet tall and live in groups called colonies. Emperor penguins are one of few species to breed over the Antarctic winter and have many adaptations that allow them to thrive in the coldest location on the planet (luckily while I was there it was the relatively warm summer season and our coldest day was -35brrrrr). Emperor penguin colonies can be found on open ice areas around the Antarctic continent where they breed, raise their young, and forage at-sea. The first breeding emperor penguin colony, in fact, was located at Cape Crozier on the Ross Sea in 1902 as part of Captain Scott’s Discovery Expeditions. Although we have known about emperor penguins breeding at Cape Crozier for more than 100 years, the at-sea behaviors and strategies of penguins from this colony have never been described.

Why Study the At-Sea Behavior of Emperor Penguins?

The effects of climate change are rapidly altering Southern Ocean dynamics including the melting of vital ice formations that emperor penguins rely on to raise their young. For example, our trip to Cape Crozier in 2018 was delayed by one year due to strong storm events and warm conditions that reduced the extent of the sea-ice formations that emperor penguins rely on to raise their young. In this case, the sea-ice melted and broke apart faster than the emperor penguins were able to raise their chicks and likely resulted in the death of most if not all the new chicks from that year.

Photo credit: RNZ / Alison Ballance

A recent publication by Schmitt and Ballard (2020) documented this catastrophic event during the 2018 breeding season at Cape Crozier as seen in the images above (Image 4). Events like these are becoming more common and the predictive outlook for this species is not looking good. It is predicted that the emperor penguin population will be drastically reduced within our lifetime due to climate change and the effects are already greatly impacting this species(S. Jenouvrier et. al 2009, 2014). While the relationship between sea-ice and emperor penguin declines have been documented, we still have much to learn about key aspects of the emperor penguins’ ecology including their at-sea behavior. Furthering our behavioral understanding of how this species responds to changing conditions will allow for a better assessment of their vulnerability to climate change.

What aspects of their behavior are we interested in studying?

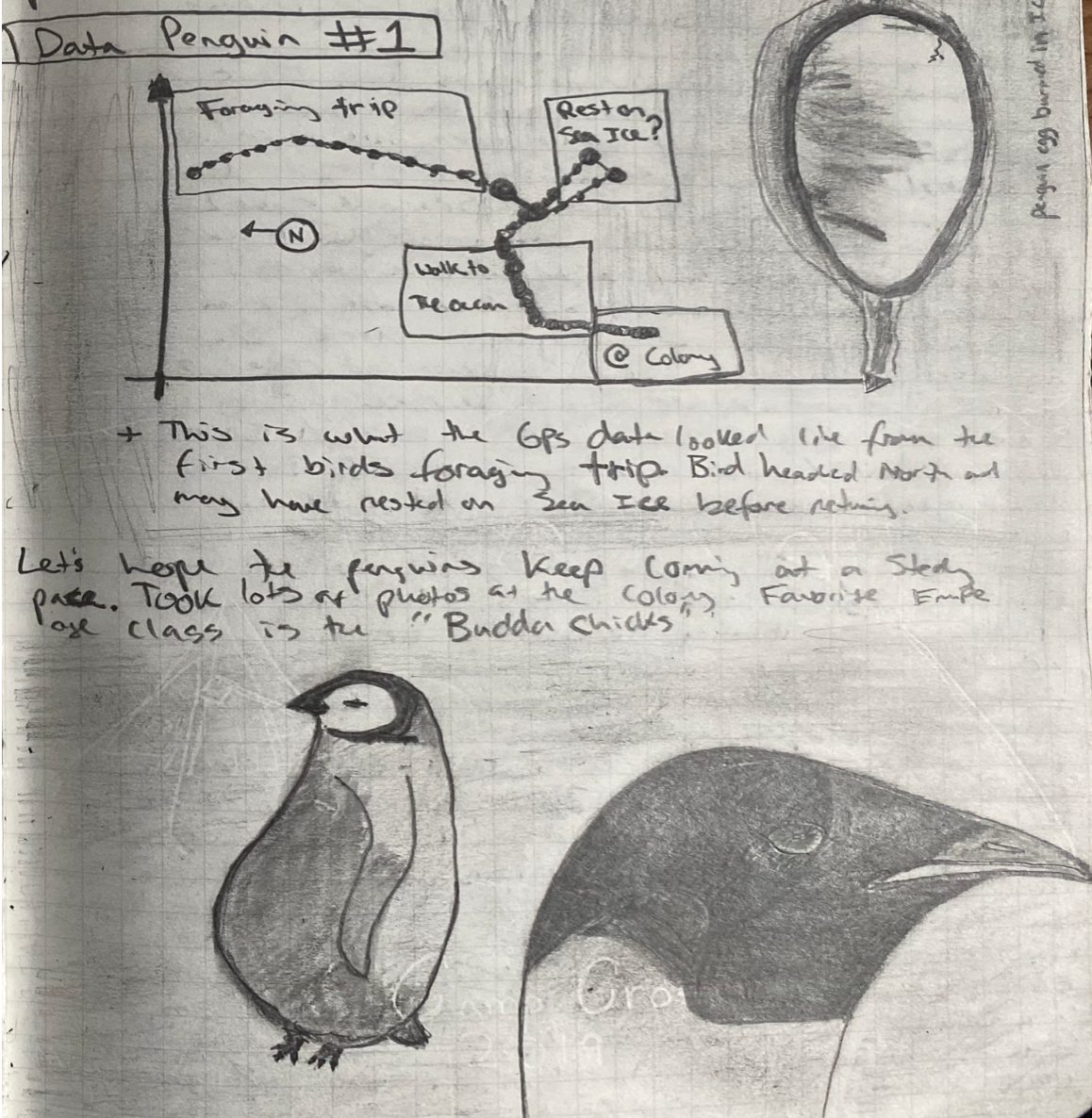

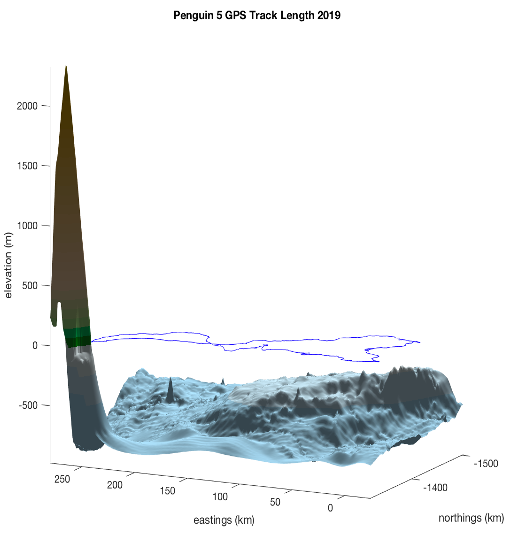

We are interested in learning more about where emperor penguins are going while they are at-sea (tracking their GPS positions), how they move (using an accelerometer to measure the orientation of their movement), the depths of their dives (depth sensor that measures pressure). From all of these data we are able to get a better understanding of where penguins are going, at what depths they are searching for food, and how far and for how long they travel. These measurements are vital to furthering our understanding of how emperor penguins acquire the food to support the growth of their chicks (check out the happy chick drawn in my field notes (Image 7).

What About Penguin 5? You Never Told Us What Happened.

After we recaptured penguin 5 and removed the biologger, the penguin returned to the colony and delivered food to its hungry chick. We returned to our camp, warmed up our cold hands and downloaded the data to our computers. To our surprise penguin 5 traveled over 1000 kilometers (~621 miles) roundtrip and gained 1 kg (2.2 lbs.) of weight during that 17-day duration. This penguin also made some impressive dives down to 485 meters (1,591 feet)! Trust me, I have gone over the data many times, pinched myself twice, and indeed these numbers are accurate and spectacular. Among all seabird species, emperor penguins are truly the world’s greatest divers and are an incredibly well adapted species that we still have much more to learn about. More information will follow in our vert lab blog as we continue to dive deeper into the data we collected during our exciting expedition to Cape Crozier.

Until then, stay safe, huddle-in-place, and stay tuned,

Parker and the Emperor Penguin Field Team

Thank you to our collaborators, funding agencies, university, field support that made this research possible.

We would like to thank our collaborators at NIWA and funding from the Ross Sea Research and Monitoring Programme. Additional funding to support travel costs and field gear came from National Geographic and SeaWorld. In addition, we would like to thank Moss Landing Marine Laboratories and staff as well as our affiliated universities San José State University and California State University Monterey Bay for their support. Last but not least, we would like to thank the logistic field support from the staff at Scott Base, and the emperor penguins at Cape Crozier that made this research possible. Thank you!

All work was performed under permission and in accordance with the New Zealand Foreign Affairs & Trade.