By Lauren Cooley, MLML Vertebrate Ecology Lab

By Lauren Cooley, MLML Vertebrate Ecology Lab

The hotline rang at 2pm and I quickly ran across the lab to grab the phone, excited to find out what new adventure awaited me. “Moss Landing Marine Laboratories Stranding Network, this is Lauren,” I answered. The caller had been out for a walk on Del Monte Beach in Monterey, California and had stumbled upon a deceased California sea lion. He relayed to me his location and a brief description of the animal. I thanked him for reporting the sea lion to our hotline, packed up my equipment and headed out the door, excited for another glamorous (or maybe not) day of marine mammal field work!

The MLML Marine Mammal & Sea Turtle Stranding Network responds to all dead stranded pinnipeds (seals and sea lions), cetaceans (dolphins, whales, and porpoises), and sea turtles in Monterey County, California. We collect data from animals ranging from 30-pound harbor seal pups to 40-foot long humpback whales (shown above), and everything in between. Our stranding network is run by graduate students and interns of the MLML Vertebrate Ecology Lab.  We are permitted by the NOAA Marine Mammal Health and Stranding Response Program to do this work, alongside a diverse group of stranding networks around the country. Some stranding networks, like MLML, only respond to deceased animals to collect important scientific data. Others, like our local organization The Marine Mammal Center, rescue sick and injured marine mammals and then rehabilitate them for release back into the wild.

We are permitted by the NOAA Marine Mammal Health and Stranding Response Program to do this work, alongside a diverse group of stranding networks around the country. Some stranding networks, like MLML, only respond to deceased animals to collect important scientific data. Others, like our local organization The Marine Mammal Center, rescue sick and injured marine mammals and then rehabilitate them for release back into the wild.

Marine mammals and sea turtles both play important ecological roles in marine ecosystems, but they face a number of severe threats including human-induced climate change, polluted oceans, entanglement in marine debris, poaching, and vessel collisions. In light of these threats, it is essential that we study the health of these populations and document their mortality trends. Only when we know why certain animals are dying can we enact conservation efforts and policy changes to protect them. The MLML Stranding Network thus has two main goals: 1) figure out how many marine mammals and sea turtles are dying in Monterey County, and 2) determine why they died. We accomplish these goals by investigating dead animals reported to us by the public. We document life history information (animal species, age class, and sex), collect tissue samples for analysis, and perform animal autopsies (called necropsies) to determine cause of death. We also assess every stranded animal for signs of human interaction, such as gunshot wounds, ship strike injuries, or entanglement in marine debris.

Enough background info… let’s get back to my sea lion call! 30 minutes after answering the phone, I reached the animal I was searching for on Del Monte Beach. It was a juvenile California sea lion, the most common marine mammal species we see here in Monterey Bay. The carcass was starting to smell, indicating to me that the animal had died several days prior. I donned my personal protective equipment and began my examination. I first assessed the animal’s external body for any signs of illness or injury, either natural (shark bite) or human-caused (entanglement in fishing gear, wounds from a vessel trauma). The animal was underweight, but there were no visible scars or injuries. I then determined the animal’s sex (male) and measured the total body length from nose to tail (110 cm). Next, I tied a small piece of green twine around the animal’s foreflipper to indicate to my fellow stranding responders that we had already been to this animal. Finally, after plotting the GPS coordinates on my phone, I recorded all the information on my datasheet.

I next had to make a decision about whether to recover this animal and take it back to the lab for further examination or leave it on the beach. Unfortunately, it had already begun to decompose so it was not a good candidate for recovery. Decomposition is one of our main enemies as stranding responders, as it quickly erases the clues we are looking for to assess animal health and ultimately determine cause of death. I decided to leave the animal where I found it on the beach to decompose in its natural environment. Based on my brief external exam, my best guess was this sea lion had died of malnutrition, an increasingly common cause of death for marine mammals around the world struggling to find food in rapidly changing ocean environments. As I walked down the beach back to my truck, it seemed likely the rising tide would soon sweep this sea lion back out into the Bay, where it would find its watery grave.

Dr. Jim Harvey founded the MLML Stranding Network in 1990. In the 30 years since, we have responded to over 3,500 deceased marine mammals and sea turtles! Generations of Vertebrate Ecology Lab graduate students have helped collect rigorous, high quality data from these animals that have contributed to numerous MLML master’s theses, scientific publications, and government reports. Our Stranding Network helped discover a new species of beaked whale, documented mass strandings of California sea lions during the 2013-2017 Unusual Mortality Event, and are currently helping the federal government determine why Guadalupe fur seals are stranding in such high numbers in recent years. Many things have changed over the last three decades, but as long as there are marine mammals and sea turtles in Monterey Bay, our stranding work will never be done.

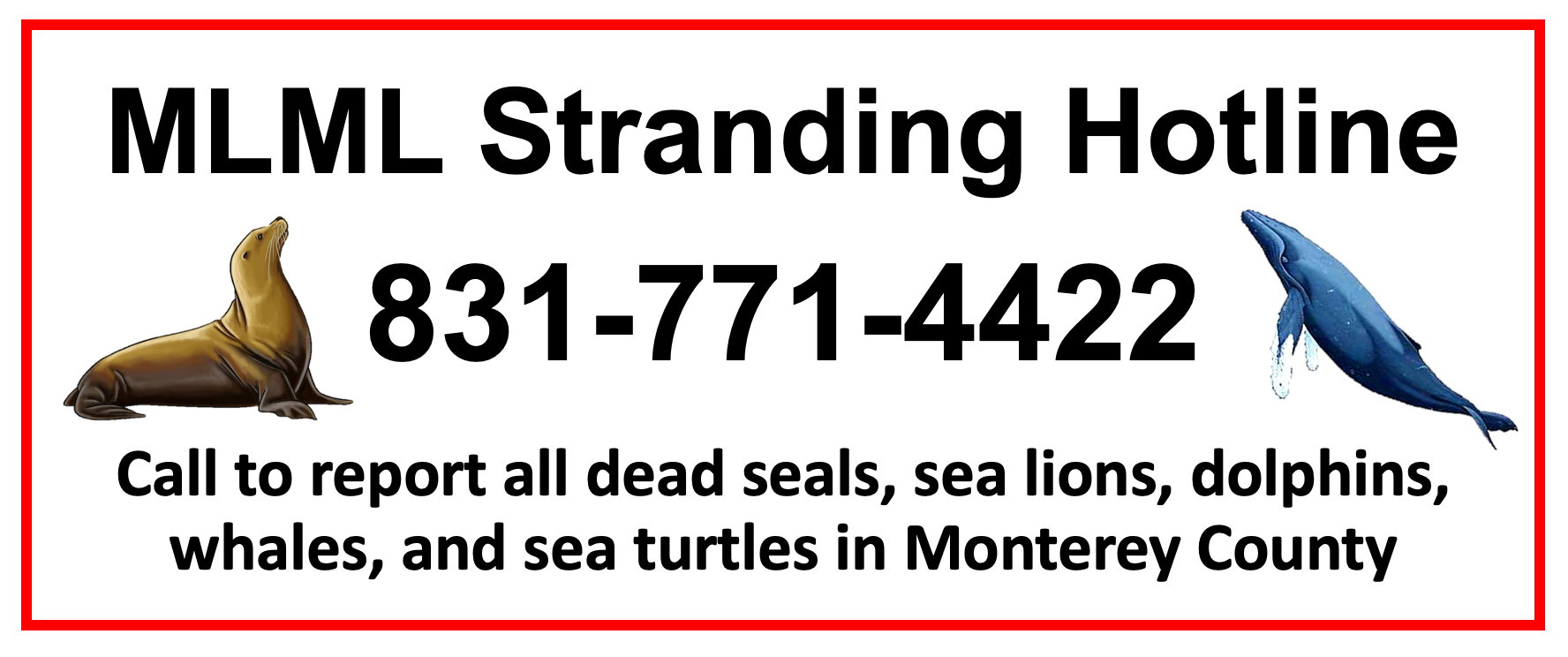

The MLML Marine Mammal and Sea Turtle Network needs your help! We rely on the public to report stranded animals to our hotline. If you find a dead pinniped, cetacean, or sea turtle in Monterey County please keep your distance and call us at 831-771-4422.

All stranding activities shown here are permitted by the National Marine Fisheries Service.