by Shandy Buckley, Physical Oceanography Lab

In April of this year I flew off to sunny, warm Hawaii to participate in a research cruise for my former school, the University of Hawaii, Manoa. As the plane took off from San Jose in a cold morning rain I had little idea of what to expect, science wise. On my arrival in sunny Hawaii I quickly learned that the cruise was funded by the US Air Force, (and specifically an agency called DARPA) to observe a glider do something where no one else could see it. The details were vague, to the point that until the evening after we’d left port none of the ships crew, nor myself knew where we were exactly going or what DARPA stood for. We took to referring to it as the ‘Department of Defense Against the Dark Arts’, and the giant satellite tracking antennae on our deck as the ‘death star’.

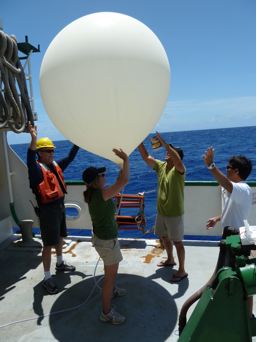

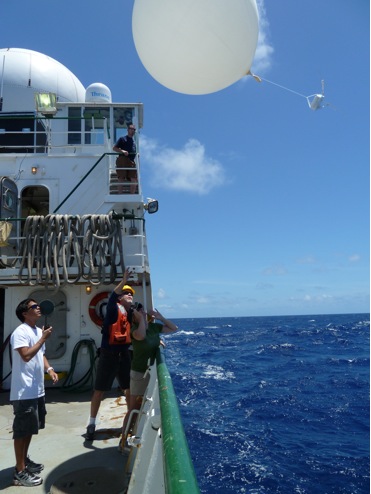

Silly names aside, my job aboard the ship was to collect atmospheric data using weather balloons. Before leaving land I was trained by the UHM meteorology department to launch weather balloons and convince the attached instrument to listen to me. The instrument, all going well, would profile the atmospheric density (pressure, temperature, humidity) to over 30,000 meters. Once on station, 1,000 nautical miles west of Hawaii, I would launch a balloon every 6 hours and take meteorology readings at the surface. On land I was referred to as the balloon technician.

The title of “Chief Scientist” was bestowed on me jokingly one night at dinner and stuck through the entire cruise. The reasons for such a prestigious title were two-fold. First of all, I was the only person on board associated with a research institute who was there to collect research data. The rest of the science party consisted of 4 very intelligent technicians contracted or hired by the Air Force whose job on board was to collect satellite data transmitted from the glider. Second of all, as the only woman on board, I was given the Chief Scientist cabin. And that is how a first year graduate student becomes Chief Scientist.

Being at sea for 16 days, literally 1,000 nautical miles from “civilization,” on a 200-ft ship with 20 men is an interesting and very educational experience. The other people on board had a lot to teach me. The lead technician led me through the basics of communicating between the scientists and the bridge in the middle of the night, and how to launch a large unwieldy object without following it over the side of the ship. Every morning I would go up to the bridge and the Captain would patiently guide me through a sun sight with the sextant. By the end of the trip the GPS and I were mostly in agreement. Being out at sea was an incredible experience and one I would recommend to anyone with an interest in packing as much learning and action into as little time and space possible. The stars were gorgeous, the people were interesting, and the food was great.