by Kristen Green, Ichthyology Lab

Being surrounded by hundreds of penguins can sometimes make you feel like you’re losing your mind, but luckily, we also work with other bird species. The first of these are skuas, predatory birds that have conveniently timed their arrival to the island just as the penguins start to lay their eggs. The skuas harass the penguin colonies relentlessly, and with greedy success. Today I saw a pair of skuas working the colony, one swooping on a nest, scattering a skittish penguin, while another one grabbed the egg. Skuas pair up, often with the same mate season after season, and patrol and defend their territories. Each of us is responsible for covering a set of territories throughout the season to record skua sightings and track the reproductive success of breeding pairs.

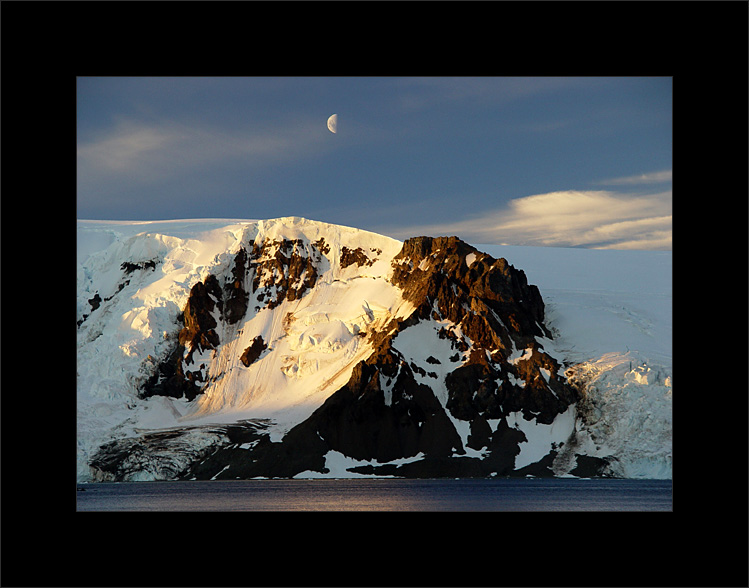

I like my skua rounds; our work is solo, and one of the few times you get to be alone here. My route takes a few hours and follows a circuitous route over hills and moraines with incredible views of the island and the bay. This is an island that can completely reinvent itself from day to day, and sometimes even hour to hour and I have yet to get tired of seeing a different view each day. My route ends near the beach, at a huge rock formation aptly named the Sphinx. Near the Sphinx, the tiny Antarctic terns cry and swoop to defend their nests.

I like these birds because they are beautiful; when silhouetted against the sky, their white bodies look almost translucent except the flash of orange beak. Also, weighing in at just over 100 grams, this is a bird that cannot hurt me. The penguins (with good reason) rail at my shins, inflicting flipper-slapping bruises, and tear up my hands with rapid fire pecking. The skuas (I’ve heard) hurl themselves at intruders to defend their territory once they have laid eggs.

The end of our week was a visit to the Polish station, to do some work at colonies there and take showers. The Polish winter over crew was leaving, and the summer crew was coming in, so about 30 new scientists and crew had just arrived, including a group of snow scientists and glaciologists (scientists who study glaciers, naturally), who informed us that the glaciers here are 18,000 years old!

We woke up the next day, planning to do more work at our skua territories near the Polish station but the barometer was dropping and the wind picking up. We decided to head home, but when we got to the bay, there were already white caps and waves breaking on the gravel bar. Three of us decided to attempt to cross in the canoe while Sue, our boss, waited on shore. We made it a short distance from shore before freezing waves were breaking over the nose of the canoe. We quickly retreated in a dicey turn around to shore. On shore, we reevaluated. Nobody wanted to stay another night at Arctowski, plus we had work to do at Copa. Option 2 was crossing over the glacier.

I was a little nervous about the glacier, a) I’ve never crossed one, and b) all morning I’d heard from one of the Poles how dangerous the glacier is right now. The first crossing early in the season is the most uncertain, as the crevasses, or cracks in the glacier, are still covered with snow and difficult to see. The glacier has receded significantly in the past few years, and the old route is now eroded or passes through giant crevasse fields. The others seemed confident about choosing a new route farther back from the glacier edge. We put on harnesses and roped ourselves together, as I asked, “So, ummm, what do you do if you fall in a crevasse?”

The answer: “Brace yourself and the others will pull you out with the rope.” Dave, the field leader led us across this ancient mound of snow and ice, poking his trekking pole across every step of the way to verify solid footing. It took us almost an hour to cross the glacier, with howling winds toward the end, but we made it safely. It was an adventure and once I stopped being scared, it was fun. We hiked the remaining mile or so back to Copa. Knowing that our penguin colonies must be worried because they hadn’t seen us all day, and were anxiously waiting for us to record their presence, we headed off to do our rounds.

- A Southern giant petrel on its nest (photo: Lara Asato)