Editor’s note: Graduate student Nathan Jones will be spending summer 2008 aboard a research vessel studying seabirds in the Alaskan Bering Sea. During his occasional access to internet, he will send back dispatches that we will post here. This is his second “Birds of the Bering Sea” installment.

by Nathan Jones, Vertebrate Ecology Lab

May 31, 2008, 8am. Anchorage, Alaska – The sun is shining this morning in Anchorage, Alaska. Today will be another in a week of days marked by growing warmth. The mountains to the east are greening in a rush as winter snows retreat, and summertime is arriving with a certainty that is felt by every living thing.

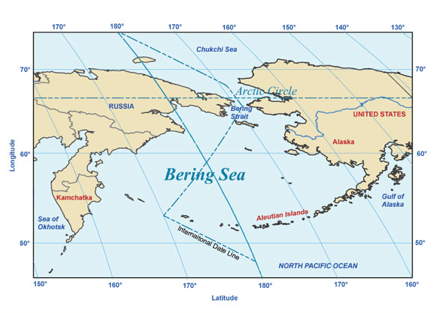

At this latitude it seems like the daylight is endless, and I sit reveling in this feeling as I wait for news of my flight to Dutch Harbor. I am scheduled to fly out tomorrow on a twin engine prop that has been chartered by NOAA to carry a group of biologists to meet our research vessel, the Oscar Dyson. Dutch Harbor is a bustling fishing port, tucked in the protective, folding coastline of Unalaska Island at the base of the Aleutian Island chain. It is a major hub for all the fishing activity that goes on in the Bering Sea, and has recently been made famous by the Discovery Channel’s “Deadliest Catch” series.

After breakfast I get the call. It is not sunny in Dutch Harbor. In fact, it is blowing 25 knots and raining sideways, with visibility down to a few hundred meters! This kind of weather might seem difficult to imagine at the end of May, but such rough conditions are not that uncommon for the Bering Sea, even in summertime. And, although Alaskan pilots are some of the most skilled aviators in the country, they are wise enough to know when it’s just too dangerous to fly. So the airport in Dutch is closed, and I will have to wait in the sun here in Anchorage, hoping for better weather…

June 1, 2008, 5pm. Enroute from Anchorage to Dutch Harbor, Alaska – The weather in Dutch Harbor has cleared somewhat, and we’re all ready to go! It will be a full flight – 26 scientists, sitting shoulder to shoulder – all going to meet ships to do their research on the Bering Sea. Because the plane is small we’re limited in what we can bring; most of these people have shipped their bags ahead, and are bringing less than 20 pounds each! Luckily, my coworker Marty and I have been granted an exception, because our reference books, computers, binoculars and other equipment weigh almost 30 pounds already. I have reduced my personal baggage to some basics: 22 pounds of clothes, shoes, and gear to last me three weeks. The props on the engines are turned, and begin to spin. They whir. Then they roar. I put in some earplugs to dull the noise, and the plane races down the runway and launches into the air. We’re off!

I’ve always been impressed when flying, and it’s a pleasure to peak out of the windows and watch the rugged, snowy mountains divided and sculpted by living glaciers that are melting into turquoise rivers heavy with silt, then spreading wide into vast stretches of wetlands that sweep to the horizons in all directions under the plane. It’s almost too immense for words. These pictures depict the landscape that I am flying over, courtesy of the US Fish and Wildlife Service.

We must stop in King Salmon to refuel. This should be a routine task, but once on the ground the pilots inform us that the plane is in need of an emergency inspection; a smoke detector in the cargo hold has been lighting up for no apparent reason. It is already 8 pm, and we still have a couple more hours to fly to get to Dutch Harbor, but no one here is going to complain about any inconvenience. Better to be safe than to risk plummeting in a fireball into an untracked wilderness, I say! There’s now enough time to unfold myself and get out of the little plane to grab a sandwich from the (only) store. Better to eat now, because I suspect it’s going to be a late night…