By Catherine Drake, Invertebrate Zoology Lab

The Marine Ecology class recently boarded the our research vessel the Point Sur for a trawling expedition. The plan for this field trip was to run three—one mid-water and two benthic—trawls. The benthic zone is the lowest level in the ocean and includes the seafloor, which is a habitat that has a lot of biodiversity. So, it was expected that the nets would bring up many intriguing organisms, and they did not disappoint! The most prevalent invertebrates we captured were urchins, specifically red and heart urchins, but I want to focus on the slightly bigger invertebrates that caught my eye: three octopi!

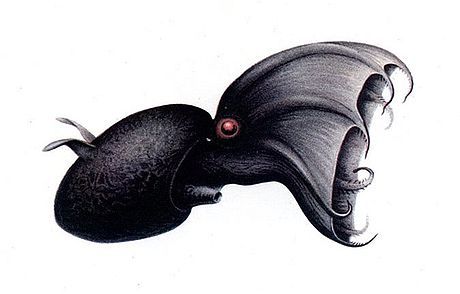

Octopi are incredibly intelligent and have highly developed nervous systems with 500 million neurons, which to put in perspective is in the same level as cats and dogs. Although we are unsure what species of octopus we captured, we believe that these amazing cephalopods are most likely east Pacific red octopi. The east Pacific red octopus, Octopus rubescens, is a small octopus ranging from 40 to 50 cm in length, and researchers who study this invertebrate say that it can easily solve puzzles and has an incredible memory. So, after the Point Sur docked, we immediately took the octopi to our aquarium room to place them in their own tanks, which we filled with toys for them!