by Emily Donham, Ichthyology Lab

“What have I done!?” This is my first thought as I plunge into the frigid waters at Stillwater Cove. Having just moved to Moss Landing after spending the past eight years in tropical Hawaii, this is my first chance to dive in California’s temperate waters. My dive computer reads a mere 54° F, but that can’t be right. This water feels much closer to freezing. Once I’m able to recover from the initial shock I realize that my arms just don’t bend the way they used to. This is mostly due to the 10 mm of neoprene wrapped around my body to help keep me warm. I used to be able to get away with just a 2mm top! I slowly become acclimated to the temperature and limited mobility and descend to the depths for my first glimpse into the kelp forest ecosystem.

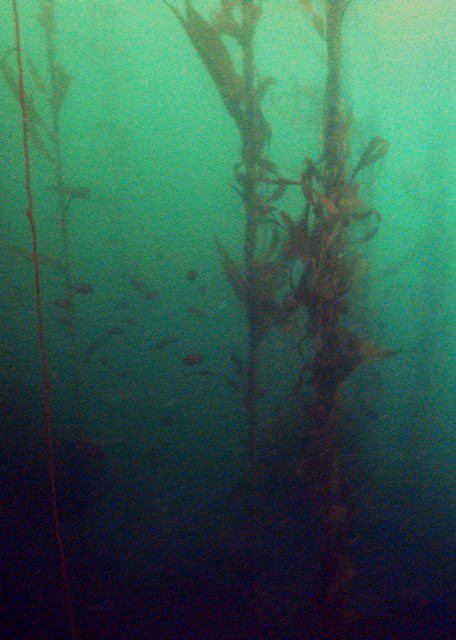

Unfortunately, today isn’t the greatest of visibilities. The water has a greenish hue and I’m not able to see beyond about 15-20 feet, but even so, there is still a lot to get excited about. Coming from the tropics where reef-building hard corals are the main attraction, it’s hard to believe that macroalgae could ever be so breathtaking. Some of the giant kelps at our dive site are over 60 feet tall, which makes it easy to see why people refer to their ecosystems as forests. I look closer and see small groups of juvenile rockfish intermingled within the kelp, utilizing its blades for shelter. The closer I look, the more I see, and I start to realize it’s going to take me awhile to learn what everything is, despite the lower species abundance and diversity compared to tropical coral reefs. It certainly doesn’t help that the muted colors here make differentiating between species tricky. We ascend to our safety stop and a sea lion swims in to check us out.

At the end of my dive day I look back and am once again reminded of why I decided to study marine science and I can’t wait to jump back in the water as soon as possible. Luckily for me, as a student of the Ichthyology lab, my advisor has decided to make biweekly dives a part of our education. Hopefully exploring California’s coastal waters will help in my search for a thesis topic.