by Alexis Howard

Seasons changing kelp

Many competing stages

Pheromone driven

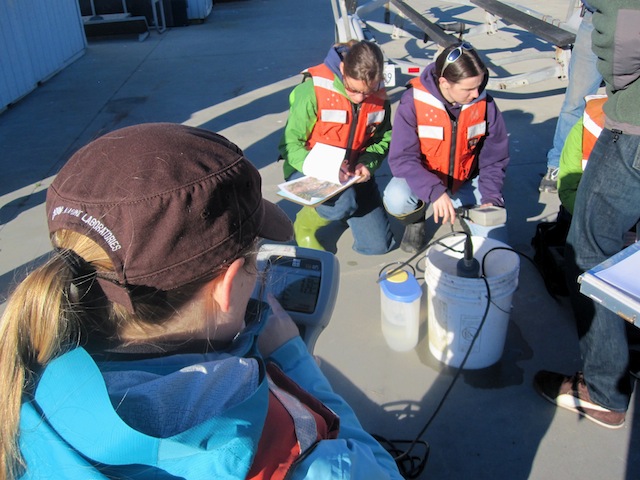

In a day that some might describe as “the ideal lab experience,” four Moss Landing students set out to perform water sampling techniques for their chemical oceanography class, and enjoyed a day filled with surprises and adventure on the Monterey Bay. Those students, from the phycology, physical, and biological oceanography labs, took MLML’s “Hurricane” Zodiac boat out to nine sites around the bay to collect seawater. Along with two other groups that explored sections of Elkhorn Slough, the sampling effort was a snapshot of the concentration of silica in the surface waters of the bay and slough.

The day began with a lesson on instrumentation for determining temperature and salinity at each collection site.

En route to one of the sampling sites, phycology lab student, experienced boat driver, and keen marine mammal spotter Mike Fox caught sight of a pod of over 50 dolphins! As the boat slowly approached, a handful of the common dolphins gracefully whizzed along by the boat and gave the delighted marine science students quite a show. Read more

It started as any good weekend day might. A good cup of coffee, a good book, and a view of the bay. I like to park my car looking out over the tidepools at Asilomar and read, letting the crashing waves add interesting sound effects to whatever scene is playing out in my current novel of choice. Knee deep in Jurassic Park, the waves were bringing to life velociraptors crashing through the forest. Intimidating and terrifying, those velociraptors. But you can’t help but admire them, and the juveniles sound pretty cute. Given the chance, I’d probably take a baby velociraptor for a pet. At least until it started stalking me around the house.

When the sounds of my empty stomach started overpowering the thundering waves, I headed home to make some lunch and get things in order for the coming week. Not two steps into the kitchen my phone buzzed, signaling the arrival of a text message. More often than not, I’d have ignored it, as hunger usually wins out in my ranking of priorities. But as all things happen for a reason, I decided to take a look, and so for once, my phone didn’t get forgotten for hours on end as it usually does.

“hey gray whale calf alive and stranded near monterey dunes colony. TMMC is headed to the scene, we may need ur help! r u available today?”

I had to read the message twice. As much as people might think all marine biologists spend hours on end with dolphins, whales, and other majestic creatures of the sea, learning their mannerisms, capable of identifying any sleek shape that might be surfacing in the bay on a giving day, I hadn’t actually even seen a whaleup close. My closest call was a pod of orcas sighted from the bow of the Point Sur during a class cruise, and I just caught a glimpse of their backs as they headed away. Usually, my most intimate experience with whales was seeing the poof of sea spray that they leave like a footprint above the water, the proof that one of the giants had just taken a great breath before submerging. I really don’t know much about whales. I study seaweed.

While on a beach down in Chile, South America the Moss Landing Marine Labs Global Systems class stumbled on a series of interesting rock features. The low silica rock of Chile flows easily and comes from molten lava, when it cools it contracts and forms. These cracks that form from cooling are roughly 6-sided, or hexagonal, and can form huge columns as seen at California’s Devils Postpile National Park. We took the liberty of testing the rock’s structural integrity while trying to climb these amazing columns. The columns seem man made, but knowing some basic geology helps to determine the origin, even when in another hemisphere from home.

The Moss Landing Marine Labs Global Kelp Systems class went to Chile and learned to process samples of algae and invertebrates to get carbon and nitrogen isotopes. These isotopes were collected to help scientists learn about the impact of creating a kelp farm where kelp would not have been otherwise. Algae and inverts have different isotope signals, so isotopes can help in tracking where nutrients go. What did this kelp crab have for dinner? Looks like algae from the kelp farm!

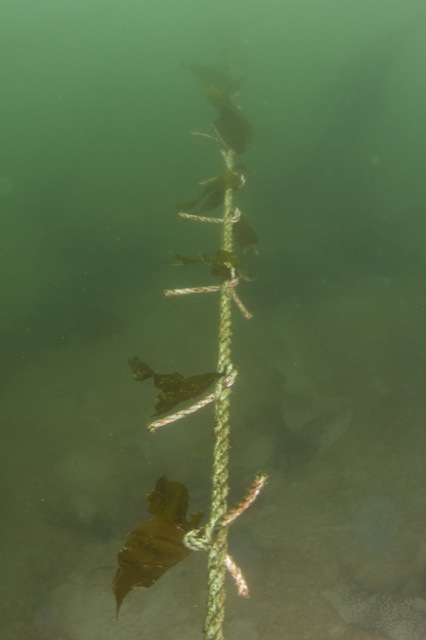

The Moss Landing Global Kelp Systems class was fortunate enough to dive in a kelp farm designed to grow Giant Kelp, Macrocystis pyrifera on lines. The kelp farm had large kelp crabs which aggregated because the kelp is their preferred food, similar to insects eating on our crop fields on land. The cute baby kelp is shown below growing on lines, hopefully they will not be eaten and make it to adulthood. It was an interesting experience seeing an underwater farm, its easier to farm in the water with kelp as the nitrogen fertilizer is naturally in the water!

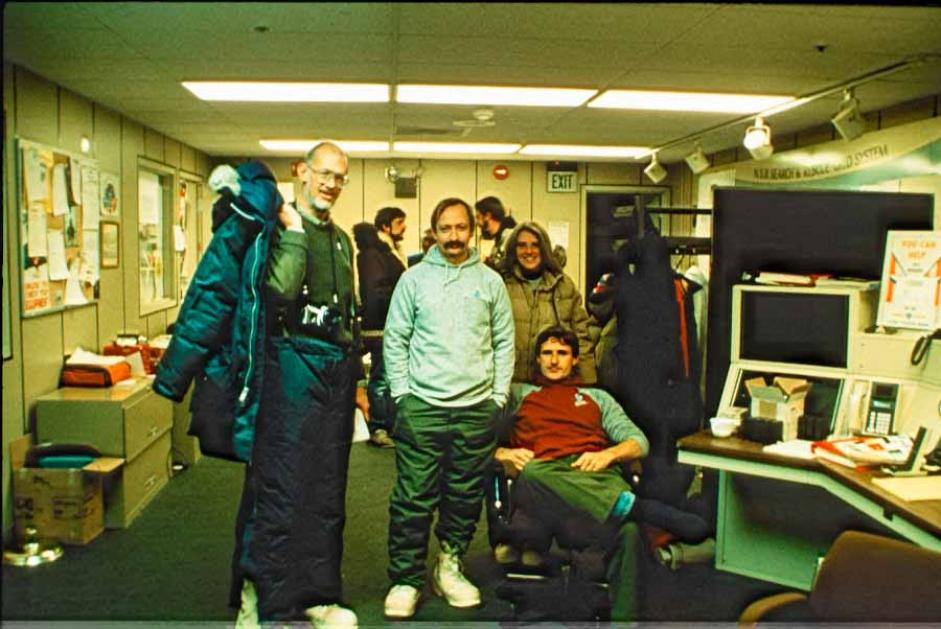

Tomorrow, Big Miracle will open in box offices across the nation, telling the story of the 1988 rescue of three gray whales trapped in the ice near Barrow, Alaska. Dr. Jim Harvey, MLML Director and professor (and MLML alumnus), played a significant role in the operation. Harvey, who frequently tells the story of the rescue to his grad students and now has proof of his whale-tale, sat down with us and agreed to paint the picture one more time, and fill in some of the lesser-known details.

Jim, you didn’t join the faculty at MLML until 1989, a year after the rescue operation took place? What were you doing at the time, and how did you get involved?

That’s correct; I was doing a two-year postdoc position at the National Marine Mammal Lab (NMML) in Seattle, Washington when the story was picked up in the national media. I had done a lot of work tagging gray whales in Baja, California with my advisor Bruce Mate while getting my doctorate at Oregon State University, and NMML recognized that I had experience with gray whales. My status as postdoc also meant my time was more flexible than some of the other biologists.

The scientific community originally didn’t want to interfere with the whales; generally, we try to step back and let nature work its course. However, with the whales in the national spotlight there was a lot of pressure to get involved, and since NMML had done work for years near Barrow, we were eventually asked to send biologists to help. I, along with Dave Withrow, was asked to go, with plans to tag the whales.

Do you know why the whales were there in the first place, and how they were discovered?

These three young whales were younger and inexperienced, and the truth was, they should have begun migrating south some time earlier when the other gray whales did. They were trapped near Barrow, Alaska, the northernmost city in the US, where a big ice flow had traveled down and grounded itself, effectively blocking their path south.

The whales were found by an Eskimo on a snowmobile who was coming back from a day of hunting. The Eskimo mentioned the whales to scientist Craig George. In Alaska, the native communities hire biologists to help monitor the wildlife they harvest, conduct studies, and manage the permitting, and Craig was one of these scientists. He was interested in recording some acoustic signals from the whales, but didn’t have any equipment to do so. Craig went to a friend at one of the local TV station to see if he could borrow recording equipment, and the friend obliged, and others at the station asked if they could film upon hearing the story of the whales. I don’t think Craig knew what they were planning to broadcast, but it turned out that they showed the footage on the news, and pretty soon it went viral. Read more…. Read more

Invertebrate Zoology Lab

Penguin colony on Isla Magdalena with over 60,000 breeding pairs

Isla Magdalena is a small island in the Strait of Magellan off the coast of Punta Arenas, Chile. In 1982 it was declared a national monument, Los Pinguinos Natural Monument as the breeding location for several seabird species including gulls, cormorants, and the Magellanic Penguin which has been estimated at over 60,000 breeding pairs. Magellanic penguins were named after the explorer Ferdinand Magellan who spotted the birds in 1520 as he sailed around the tip of South America. Magellanic penguins are found on coastlines on both the Atlantic and Pacific shores and are the only penguins to breed on the Patagonian mainland.

The breeding season lasts from September through February during which penguin couples dig burrows for their nests or hide their nests under shrubs. A pair may use the same burrow for years where the females usually lay two eggs that hatch after five or six weeks. Juveniles have waterproof feathers after two months and are ready to head out into the ocean, but it can take up to two years for chicks to get the full black and white plumage of the adults.

Students from Global Kelps Systems course in Chile took a slight detour (before class began) out on the ferry to the Isla Magdalena. Sara and I took off on ferry Melinka across the thankfully calm, Strait of Magellan. As the boat approached the Island we could see the lighthouse in the distance, the kelp forest surrounding the island, and a small number of penguins swimming and jumping alongside the boat. Once on shore, we got the chance to walk among thousands of Pinguinos!!! We watched as they crossed the pathway from their nests to the ocean to feed or looked after their chicks playing in the surf. It was an amazing experience to get to be so close to the penguins but at the same time it made us think about the protection laws we have here in Monterey Bay like the Marine Mammal Protection Act. A few of the visitors to the Island did not respect the privacy of the penguins, it is important to remember that as visitors we need to keep our distance and not chase after the animals.

The populations of these penguins are being threatened by the commercial fishing and the oil industry, which depletes schools of fish and the birds become entangled in the nets. It has also been estimated that more than 40,000 penguins die in Argentina and in the Falkland Islands each year due to oil pollution. The Wildlife Conservation Society has been working with local partners in Patagonia since the 1960’s helping to conserve these flightless birds, and in 2008 helped achieve two victories for the Magellanic penguin in Argentina: a ban on commercial fishing at Burdwood Bank and creation of a marine park at Golfo San Jorge. These victories are key to protecting habitats for the birds and their prey.

This week marked the beginning of the semester at Moss Landing Marine Laboratory and also happened to be the start of a new year. January 23rd, 2012 was celebrated throughout the world as Chinese New Year. This year, the year of the dragon, is said to be the luckiest of the 12-year mathematical cycle of the Chinese Zodiac. So to all our blog readers out there, good luck and Happy New Year!

MLML alumna Mariah Boyle has been busy. Since finishing her thesis work in Ichthyology at MLML, Mariah has found work with Fishwise, a sustainable seafood consultancy located in Santa Cruz, as Assistant Operations Director. In addition, she has found a way to merge her passions for science, travel and social justice into action. Last night, attendees of the bi-monthly Friends of Moss Landing seminar series were treated to the inspiring story of Mariah’s recent endeavors to enhance fisheries management in Sierra Leone.

With a backdrop featuring stunning photos of the land and people of the Freetown Peninsula in Sierra Leone, Mariah filled the audience in on some socio-political history of the region. Years of corruption and violent war have left this nation; rich though it is in an abundant diversity of natural resources; mired in poverty and weak infrastructure. Fish are what Mariah knows, and as it turns out fish are of great importance to the people of Sierra Leone. Smoked in the coastal villages and transported “upcountry”, fish provide a primary source of income and protein for people throughout the country.

Fishermen in the coastal towns craft fishing nets which are slung from the side of small boats and the catch brought in every morning to be cured and sold. Though the boats are small, they are many and fisheries data in the region hardly exists. Still, fish were plentiful until recently. The threat of piracy off the Western Coast of Africa is real and it is terrible. It is thought that 40% of the fish caught off the Sierra Leone coast are caught through IUU fishing. That is; Illegal, Unregulated and Unreported. These pirate boats use gigantic trawling nets that take everything they pass over, resulting in a tremendous amount of by catch. Though it is illegal for these massive trawlers to come within 5 nautical miles of the coast, there is little to no enforcement. Local fisherman are under direct threat by the boats and people on board. Their nets are often cut. Driven from their preferred fishing spots, the local fisherman have taken to fishing the nearby estuary.

Under duress from over fishing of both the juvenile and adult stocks, the fisheries have dwindled. And there is little management practiced at this time.

That is where Mariah drew her inspiration to bring her knowledge as a scientist into play. Ms. Boyle found funding through research grants, allowing her to return to Sierra Leone in 2011 with a goal to collect fisheries data; such as types of fish being caught, numbers and size; in order to inform community management.

She has worked to transform this information into a useable Log Book and Fish Guide with photographs of typical fish along with both local and scientific names for the fish. Mariah hopes these books can be used by the fishermen to track their own data so that the fisheries may be locally managed. During her last visit, 50-70 fish were identified and over 1000 fish were measured. She is now working up analysis on this data.

Informative documentaries on the threat of piracy to fisheries sustainability may be found at the Environmental Justice Foundation website. Follow Mariah’s progress on her facebook page and on her personal blog.