Tomorrow, Big Miracle will open in box offices across the nation, telling the story of the 1988 rescue of three gray whales trapped in the ice near Barrow, Alaska. Dr. Jim Harvey, MLML Director and professor (and MLML alumnus), played a significant role in the operation. Harvey, who frequently tells the story of the rescue to his grad students and now has proof of his whale-tale, sat down with us and agreed to paint the picture one more time, and fill in some of the lesser-known details.

Jim, you didn’t join the faculty at MLML until 1989, a year after the rescue operation took place? What were you doing at the time, and how did you get involved?

That’s correct; I was doing a two-year postdoc position at the National Marine Mammal Lab (NMML) in Seattle, Washington when the story was picked up in the national media. I had done a lot of work tagging gray whales in Baja, California with my advisor Bruce Mate while getting my doctorate at Oregon State University, and NMML recognized that I had experience with gray whales. My status as postdoc also meant my time was more flexible than some of the other biologists.

The scientific community originally didn’t want to interfere with the whales; generally, we try to step back and let nature work its course. However, with the whales in the national spotlight there was a lot of pressure to get involved, and since NMML had done work for years near Barrow, we were eventually asked to send biologists to help. I, along with Dave Withrow, was asked to go, with plans to tag the whales.

Do you know why the whales were there in the first place, and how they were discovered?

These three young whales were younger and inexperienced, and the truth was, they should have begun migrating south some time earlier when the other gray whales did. They were trapped near Barrow, Alaska, the northernmost city in the US, where a big ice flow had traveled down and grounded itself, effectively blocking their path south.

The whales were found by an Eskimo on a snowmobile who was coming back from a day of hunting. The Eskimo mentioned the whales to scientist Craig George. In Alaska, the native communities hire biologists to help monitor the wildlife they harvest, conduct studies, and manage the permitting, and Craig was one of these scientists. He was interested in recording some acoustic signals from the whales, but didn’t have any equipment to do so. Craig went to a friend at one of the local TV station to see if he could borrow recording equipment, and the friend obliged, and others at the station asked if they could film upon hearing the story of the whales. I don’t think Craig knew what they were planning to broadcast, but it turned out that they showed the footage on the news, and pretty soon it went viral. Read more….

What was it like when you arrived?

When Dave and I made it to Barrow, the town was swamped with media, scientists, environmentalists, government officials, and everyone else you could think of. There actually wasn’t even a place for Dave and I to stay. We were flown by helicopter out onto the ice where the whales were located, and given a chance to assess their condition. Unfortunately, one of the whales had recently disappeared, and was presumed to have died since there was no way for it to find another place to breathe. Possibly, loud noises had likely scared it and caused it to flee from the hole.

The good news was, however, that the Eskimos had become very efficient at cutting through the ice. There aren’t exactly a lot of trees around Barrow, so the town didn’t have any chainsaws. A generous company actually called the town and had some sent up to help with the effort. By the time we arrived, they were able to make a ~15 by 25 foot hole in ten minutes. They would cut the ice, and then use poles to push down one end. On the other end, more poles were used to push the big chunk down and under the surrounding ice. The only problem was, the whales were too scared to leave the safety of their own reliable hole, and they weren’t moving down the path they were cutting.

Since gray whales really aren’t very good at being in ice, Dave and I assumed they were probably extremely stressed and shaken. We suggested that they cut the holes much closer to the whales, which thankfully worked. The whales became so accustomed to moving from hole to hole, that eventually, a whale would pop up as soon as the newly-cut piece of ice was moved. They actually started traveling back and forth down their line of holes, maybe enjoying a little more freedom.

This must have taken quite a bit of time to cut so many holes toward the edge of the ice. How long were you there, and where did you stay, since Barrow was packed?

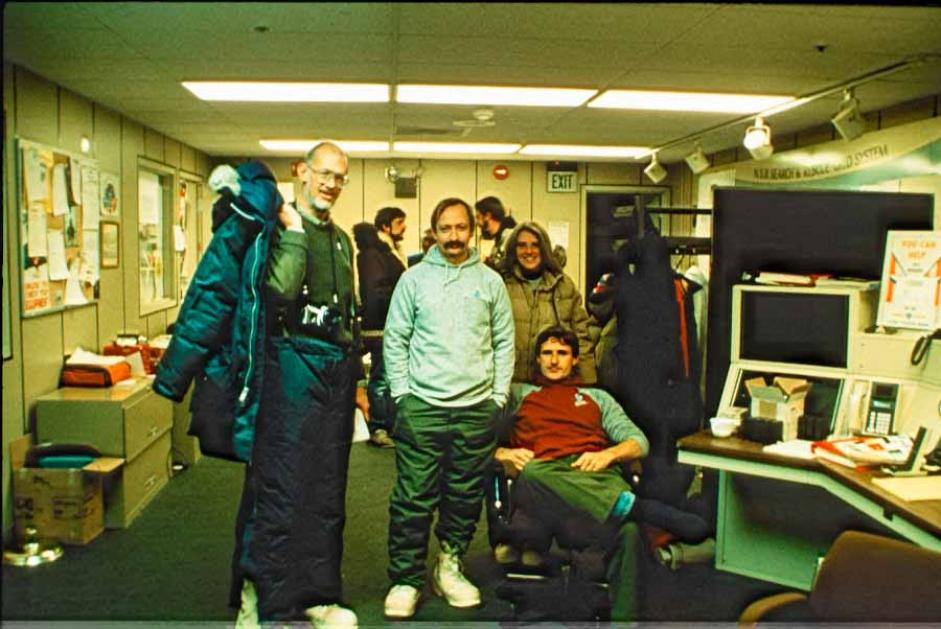

Dave and I were on site for about two weeks, and we stayed for the rest of the rescue operation. Our accommodations were actually sort of a funny story. Because of the lack of lodging, we were housed at the Naval Arctic Research Laboratory (NARL). Due to the Cold War, NARL had gained importance because of its proximity to Russia. It was a pretty top-secret place, and here we were, a couple of scientists. Well, NARL was quite a ways out of Barrow, so the only food available was from the commissary, served on a strict schedule. Somehow, our schedules seemed to be the exact opposite, and we were constantly missing all meals. As luck would have it, we discovered a Mexican restaurant in Barrow that had a limo that would come and pick you up. Dave and I spent quite a few trips riding back and forth in a limo so we could actually eat.

You mentioned tension from the Cold War, but it was a Russian icebreaker that eventually helped the whales out of the ice. How did that work out?

You’re right, there was a lot of tension from the Cold War, but the Russians did come to the rescue. The reason that we needed an icebreaker was because an ice ridge was built up against the shore, and it was far too thick to cut through. They actually considered blowing it up at one time, and took an ice expert from NOAA out to the ridge to take a look. They dropped him off by helicopter, and planned to be back in five minutes. On their way back, they found that he was being stalked by a polar bear, though he had no idea. Thankfully, they were able to get him back into the helicopter before he became a meal. In the end, they decided the icebreaker would be the best bet.

A Russian icebreaker was in the Beaufort Sea, and they were talked into helping, although there was concern because it would bring them so close to NARL and our coastline. The Russian captain and a few other crew actually ended up visiting by helicopter, and took the chance to take pictures of the scene, and shared their traditions by handing out gifts to those of us there. I can’t remember what I was given, but I remember I wasn’t able to give anything in return, because the only article I had was my jacket, and I never could have survived without it in the 10 to 20 degree below zero temperatures.

So was the icebreaker able to reach the whales and lead them to open water?

Yes, the icebreaker was actually able to plow all the way through, up to the last hole that was carved by the research team. The ship then backed out, and it created a channel that the whales were able to follow. I wasn’t able to watch from the helicopters during this part of the rescue, but there was word that people had seen the whales in open water, and others reported seeing a pair of gray whales off of the California coast. We never ended up tagging the whales because we didn’t want to further stress them out, so we couldn’t say for sure where they ended up. But, I feel confident we gave them a good fighting chance.

What do you think of a movie being made?

I plan to go see the film, and I’m curious to see how the story is told. I don’t think there’s any character in it that portrays the role I played. But hopefully now, my students wont think I’m spinning a yarn when I tell them about my part in the rescue.