Author: mlmlblog

Follow me to Open House

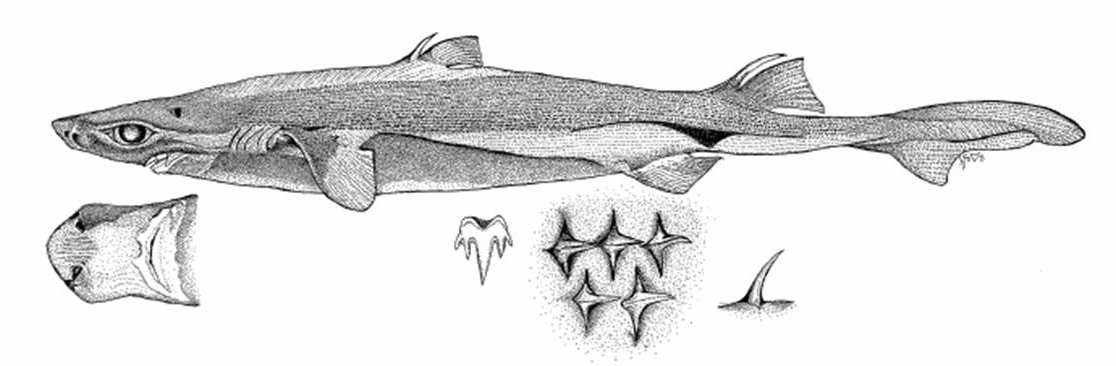

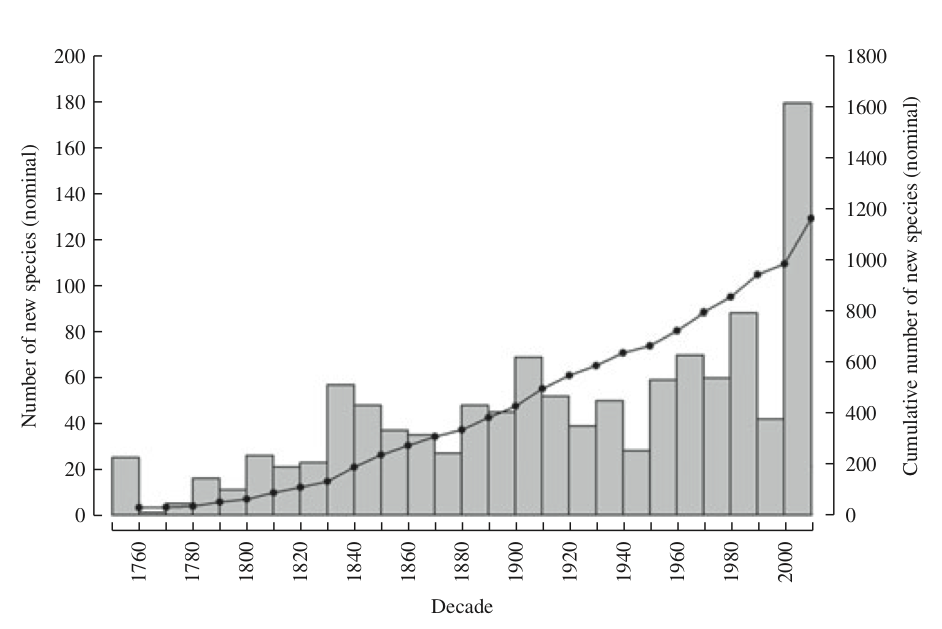

Moss Landing Scientists Contribute Four New Shark Species

Haiku of the Week: Rhinoceros Auklet Genetic Structure in the Pacific

From Diving to the laboratory

By Michelle Marraffini

Invertebrate Zoology and Molecular Ecology

Basking Shark on the Move

By Dave Ebert

Pacific Shark Research Center

A Basking Shark (Cetorhinus maximus) tagged off the California coast in June 2011 has turned up northeast of the Hawaiian Islands. The shark, which was first spotted, and tagged with a pop-up satellite tag, traveled nearly 2500 miles over the past 8 months, making this the longest recorded movement of this shark species in the Pacific Ocean. In addition to the distance moved by this shark, data on the water temperature and the depth that the shark traveled was also recorded. This information will be important in determining habitat preference and utilization.

Despite their coastal occurrence in temperate seas, this large (up to 30 feet or more) charismatic species is poorly known. This is especially true in the Eastern North Pacific where no studies have been made on their abundance or population structure. The IUCN lists the Basking Shark as vulnerable globally, but in the Eastern North Pacific it is listed as endangered. In Canada it has been listed as endangered where its population has undergone significant historical declines. More recently (April 2010) the U.S. listed the Pacific coast Basking Shark population as a “Species of Concern”.

The Basking Shark is the second largest shark species in the world and has been reported globally from high latitude seas, including arctic waters, to the lower latitudes including the tropics. The distribution of these sharks changes seasonally with their abundance shifting from higher to lower latitudes in the autumn and winter months. As they move into warm temperate and tropical seas they exhibit subtropical submergence diving to cooler waters often several hundred meters below the surface. This explains why they are rarely, if ever, seen in the tropics. Read more

Take a Hike!

By Michelle Marraffini

Invertebrate Zoology Lab

During the winter break, six students received the amazing opportunity to take the field class Global Kelp Systems, taught in Puerto Montt Chile. In the few weeks prior to the course we traveled around Chile and neighboring countries to take full advantage of this once in a lifetime opportunity. Phycology student Sara Worden, and I traveled to the Chilian National Park Torres del Paine. We were amazed at the landscape of the Patagonian steppe, enormous mountain peaks, and blue green glacial lakes that dotted the horizon. Our journey to the park consisted of a 3 day hike up to los Torres, the namesake of the park, and around to los Cuerrnos.

The mountainous group of Paine called massif consists mainly of granite and sedimentary rocks. This mountain was formed 12 million years ago (the Andes Range of Mountains formed 60 million years ago) and from a geological standpoint this landscape is considered new. The origin of the relief is from a unique combination of upheaval of the Paine Mountain Range and the erosive action of the glacial advances and reverses.

The differences in color seen in the rocks and formations are due to granite (light grey) and sediment (black or dark grey). Most of this sediment has been dated to the Cretaceous period with intrusions of Miocene laccolith.

Glacial weathering over the last ten thousand years is responsible for many of the sculptural features of Torres del Paine including the Torres where their overlaying sedimentary rock layer has been completely eroded away leaving behind the more resistant granite. Los Cuerrnos is also a great example of this glacial weathering which show dark, central bands of exposed granite with contrast their dark peaks of remnants of heavily eroded sedimentary stratum. Throughout our hike we kept using our knowledge of geology to tell the story of these thousands of year’s old formations and it made this impressive landscape even more beautiful.

Haiku of the Week: Seaweed in a changing ocean

It’s a Wonderful Lab

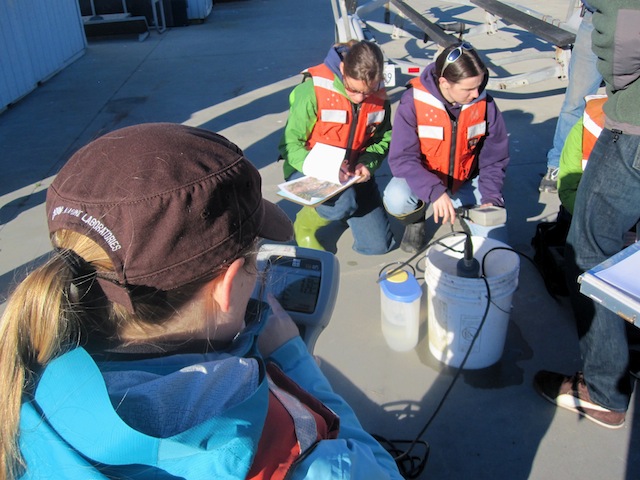

By Diane Wyse, Physical Oceanography Lab

In a day that some might describe as “the ideal lab experience,” four Moss Landing students set out to perform water sampling techniques for their chemical oceanography class, and enjoyed a day filled with surprises and adventure on the Monterey Bay. Those students, from the phycology, physical, and biological oceanography labs, took MLML’s “Hurricane” Zodiac boat out to nine sites around the bay to collect seawater. Along with two other groups that explored sections of Elkhorn Slough, the sampling effort was a snapshot of the concentration of silica in the surface waters of the bay and slough.

The day began with a lesson on instrumentation for determining temperature and salinity at each collection site.

En route to one of the sampling sites, phycology lab student, experienced boat driver, and keen marine mammal spotter Mike Fox caught sight of a pod of over 50 dolphins! As the boat slowly approached, a handful of the common dolphins gracefully whizzed along by the boat and gave the delighted marine science students quite a show. Read more

To Meet a Giant: Responding to a Stranded Baby Gray Whale

by Brynn Hooton-Kaufman

It started as any good weekend day might. A good cup of coffee, a good book, and a view of the bay. I like to park my car looking out over the tidepools at Asilomar and read, letting the crashing waves add interesting sound effects to whatever scene is playing out in my current novel of choice. Knee deep in Jurassic Park, the waves were bringing to life velociraptors crashing through the forest. Intimidating and terrifying, those velociraptors. But you can’t help but admire them, and the juveniles sound pretty cute. Given the chance, I’d probably take a baby velociraptor for a pet. At least until it started stalking me around the house.

When the sounds of my empty stomach started overpowering the thundering waves, I headed home to make some lunch and get things in order for the coming week. Not two steps into the kitchen my phone buzzed, signaling the arrival of a text message. More often than not, I’d have ignored it, as hunger usually wins out in my ranking of priorities. But as all things happen for a reason, I decided to take a look, and so for once, my phone didn’t get forgotten for hours on end as it usually does.

“hey gray whale calf alive and stranded near monterey dunes colony. TMMC is headed to the scene, we may need ur help! r u available today?”

I had to read the message twice. As much as people might think all marine biologists spend hours on end with dolphins, whales, and other majestic creatures of the sea, learning their mannerisms, capable of identifying any sleek shape that might be surfacing in the bay on a giving day, I hadn’t actually even seen a whaleup close. My closest call was a pod of orcas sighted from the bow of the Point Sur during a class cruise, and I just caught a glimpse of their backs as they headed away. Usually, my most intimate experience with whales was seeing the poof of sea spray that they leave like a footprint above the water, the proof that one of the giants had just taken a great breath before submerging. I really don’t know much about whales. I study seaweed.