Author: mlmlblog

Another One Dives the Deep: Fall Science Diving

By Scott Gabara

You dive into the cool blue-green seawater. You inflate your buoyancy compensator as you near the bottom. You check your air on your Submersible Pressure Gauge (SPG) and sign an "Ok" to your buddy. After tying off the transect tape you place your slate out in front of you, align the lubber line of your compass, and begin swimming at 300 degrees. You are identifying fish to species, placing them into one of three size bins, and recording that onto your data sheet. If this sounds like a lot to do you are right! The fall marine science diving course at Moss Landing Marine Laboratories recently celebrated the hard work they have done during the semester with a boat trip to a unique dive location. We were able to utilize MLML's R/V John H. Martin to transport us to the Carmel Pinnacles State Marine Reserve off Pescadero and anchor on a GPS point where the granite pinnacles come close to the surface.

We experienced large granitic walls and a ballet of sea lions. It was a great way to finish up the semester of diving and now mentally prepare for the final exam filled with gas laws and dive table problems. I always find myself thinking where will these divers go and what exciting dives await them after the completion of the class.

Follow the R/V Point Sur on Her First Voyage to Antarctica

By Diane Wyse

On Thursday, November 29 the R/V Point Sur, MLML’s largest research vessel and a member of the University-National Oceanographic Laboratory System fleet, set sail for Palmer Station, Antarctica. The ship and her crew, accessed for class cruises and interdisciplinary and inter-organizational research projects, will be making several stops through Central and South America during her voyage over the next several months. You can even track the trip here.

Over the course of her 8,200 mile journey the crew will post updates about all aspects of the cruise. While we will miss the Pt Sur during her first voyage to Antarctica, we can look forward to exciting updates on the Pt Sur blog.

Stay tuned for updates and stories from the crew!

Water, water everywhere but not a drop in my suit!

By Michelle Marraffini, Invertebrate Zoology and Molecular Ecology Lab

Scuba diving on the central coast means you get to see amazing kelp forests and underwater geological formations but it also often means you are getting in the sometimes frigid waters of Monterey Bay. At depth, the water can get very cold, I experienced a dive at Big Creek, Big Sur where the temperate was only 8 Celsius (~46 degrees Fahrenheit)! At that temperature my wimpy 7 millimeters feels like wearing shorts in a blizzard and gets even thinner as the pressure compresses all the neoprene bubbles in my suit. Over the years I have seen many other divers in thicker wetsuits (up to 20 millimeters on their core) and dry suits. That is right scuba diving without getting wet. When a company that makes dry suits (DUI) offered a demo day at a local dive spot my labmate Pamela and I leaped at a chance to jump in the water without getting wet.

Life After MLML: News from the tropics

By Michelle Marraffini. Invertebrate Zoology and Molecular Ecology Lab

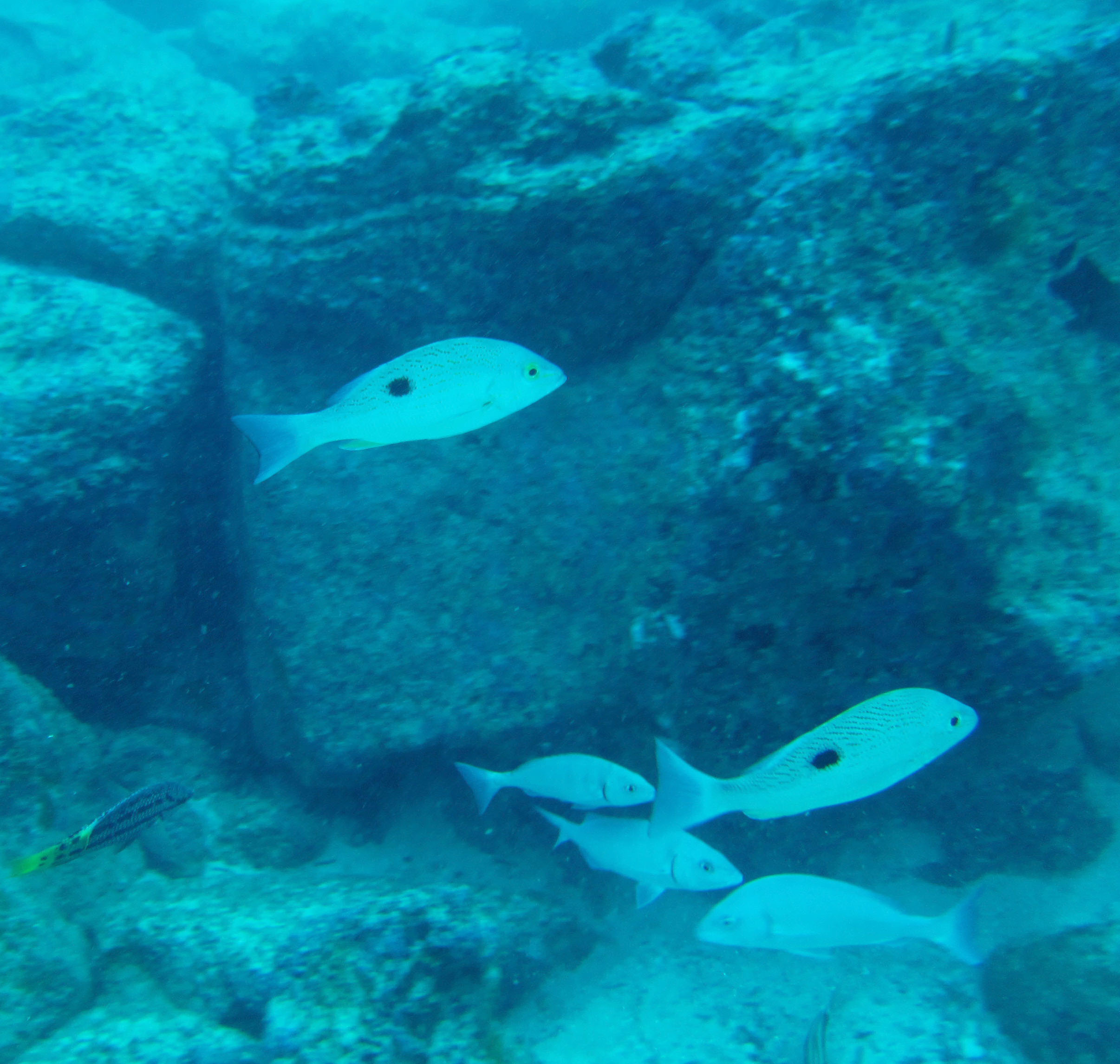

After graduating from MLML, former students go on to do great research at their new jobs or in PhD programs. One of these former students is Paul Tompkins of the Phycology Lab, who took a phd position at Leibniz Center for Tropical Marine Ecology (ZMT) in Bremen, Germany. Paul is conducting research the Charles Darwin Research Station in the Galapagos. Beyond the famous finches and the oldest tortoises, the Galapagos also boasts an impressive marine system protected by their national park. As part of a larger, ongoing project Paul is studying the role of algae in the food web and the response to climate change including El Nino events.

Photo by: David Acuna

While collecting preliminary data of the system, using underwater transects and estimates of percent cover, a diver (David Acuna) helping Paul monitor Punta Nunez came across a fish species he did not recognize. The possible identity of this fish is the species Lutjanus guttatus, Spotted rose snapper, which was cited for the first time in the Galapagos from catch data in Puerto Villamil in pervious years. If the identity of this mystery fish is confirmed it would be a new record of the species and help scientists monitor populations of fish in the area. It just goes to show that you always have to keep your eyes open for new discoveries.

The Idiot’s Guide to Funding Your Graduate Education and The National Science Foundation’s Graduate Research Fellowship Program

When one applies to graduate school, they may have found the perfect professor that they would ideally like to work with. Sometimes the two of you hit it off great and they would love to have you in their lab, but there is one thing that stands in the way: funding. It is relatively uncommon that a professor takes on a graduate student in their lab if they cannot provide funds for them through the college or through private funds. There is one way to get past this, however, without having to work and go to school part time or going into debt – find your own funding.

Typically professors fund students through one of two ways, a teaching assistantship (TA) or a research assistantship (RA). The responsibilities of these two jobs vary from institution to institution and even from department to department. Each has their own perks, but simply from what I have seen, an RA is certainly preferable to a TA. Sometimes departments even help each other out if a graduate student is qualified to TA a certain course even if it is not directly in their specified field. At my undergraduate institution for example, students in the Plant Biology department were able to TA the intro courses in the Biology department because they are qualified to assist with teaching that class and the associated lab.

While TAs are very useful in that they allow you to get paid while being a graduate student, they often require a lot of time grading for the class they are assigned. In the sciences, the graduate students with TAs usually help with grading homeworks, tests, quizzes, and oftentimes they teach labs associated with the class they are assigned. TAs, however, can sometimes only last a certain time period. My friend had been supported through a TA and though it provided her with enough money during the school year, she had zero forms of income throughout the summer because only a handful of graduate students were needed to assist with the smaller class. Additionally, TAs may only last a semester.

RAs can be just as time intensive as TAs and bring about many of the same uncertainties. While no teaching is involved with most RAs, you are still working. Just instead of being involved with the teaching side of academia, you are involved with the research side as a laboratory technician of sorts. Some professors allow your work for the RA to be directly related to your thesis while others require that they be completely separate.

8 Days at Sea

By Kelley Andrews, Pacific Shark Research Center

By Kelley Andrews, Pacific Shark Research Center

The high-pitched whine of the winch jolts me awake. I come groggily to my senses, noticing the cigarette smoke from some of the crewmembers wafting through the door of the bunkroom and the dim morning light. It’s somewhere around 5:45 am.

It is my third morning out at sea. I am on the F/V Noah’s Ark, volunteering for a leg of the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) Fisheries Research Analysis and Monitoring (FRAM) survey. The mission of the survey is to assess the health of groundfish populations off the west coast of the United States. The survey makes two passes of the coast from Washington to Southern California every summer, fishing and taking samples and data. I am part of a team of three scientists, and we are with a crew of four fishermen on the 80-foot vessel. Right now we are somewhere west of Monterey, CA.

The first tow of the day begins around 5:30 am, so we can begin processing the catch by 6:30. The winches deploy and reel in the net from depths over 1,000 feet. As I go out on deck to get ready to sort fish, I notice that the weather has picked up. The first two days were flat calm, and I had no idea the ocean could be glassy 50 miles from shore. But today the winds and swell are picking up, and it feels as though we are headed for rougher weather.

What Does a Vampire Squid Really Eat?

By Melinda Wheelock

Researchers at MBARI have discovered that the vampire squid (Vampyroteuthis infernalis) doesn't share a diet with its bloodthirsty namesake. In a recent news release, it was announced that this scary-sounding cephalopod actually feeds on the remains and waste of animals and microalgae that live in shallower waters. This "marine snow" falls through the water column to deeper water, where the vampire squid can pick it up using its unique features. The recent study observed that this creepy creature extends one of its long, thin filaments (which can be 8 times its body length!) to capture floating debris and bring it back towards its body. The vampire squid then scrapes the filament clean with its tentacles, which produce a mucus that sticks the food particles together. This is one 'vampire' that's less scary than it looks!

The vampire squid isn't as bloodthirsty as its name implies.

Photo copyright 1999 Brad SeibelFor more pictures, check out MBARI's web page dedicated to the vampire squid, here.

A Point Sur Adventure

By Kristin Walovich

The Marine Ecology class embarked on a seafaring adventure last Monday on the Moss Landing research vessel the Point Sur to observe the biota of the Monterey Bay. The class was joined by members from the Monterey Bay Aquarium, MBARI and even Professor Emeritus Greg Cailliet who arrived bright and early for a 7am departure time.

After braving choppy water and a bit of rain we began our day with a beam trawl, designed to sample creatures from the ocean floor at 600 meters depth. Unfortunately we were left empty handed when the net returned to the surface with a hole caused from large rocks lodged in the net.

Despite our first strikeout, our second mid-water trawl yielded a wide array of fish, crustaceans, jellyfish, and a plethora of other gelatinous creatures. Once on board the Point Sur, each animal was classified into separate glass dishes and recorded, giving the students a chance to practice their species identification and exercise their Latin nomenclature.

The highlight of the trawl (quite literally) was a group of fish called the Myctophids, or Lanternfish. These fish have light emitting cells called photophores that help camouflage them in the deep ocean waters in which they live. Lanternfish regulate the photophores on their flanks and underside to match the ambient light levels from the surface, rendering them nearly invisible from predators below.

The last tow of the day was called an otter trawl; but don’t worry, we didn’t catch any sea otters. This net is name for the ‘otter’ boards positioned at the mouth of the net designed to keep it open as it travels thought the water. The animals are funneled to the back or ‘cod’ end of the net and are brought to the surface for the class to observe. We saw several species of flatfish including the Sand Dab, Dover and English Sole, several dozen octopuses (or octopodes depending on your dictionary) and even a pacific electric ray.

After a long day of sunshine, high seas and amazing sea creatures the Marine Ecology students were excited with their discoveries, but also ready to be back on solid ground.

Are you my clone?

By Jessica Jang

Ever wonder why you see some anemones in groups and some alone in tide pools? Sea anemones can reproduce in two different ways, asexually and sexually. Anemones are broadcast-spawners meaning that they release eggs and sperm into the water column for fertilization. However if you're an anemone that has settled onto a nice barren rock and don't have time to reproduce, but you want to prevent other anemones from taking over that rock you claimed, what do you? You split yourself through........ FISSION! This is asexual reproduction, where the anemone splits itself and creates another one of itself of the exact same genetic material.

Ever wonder why you see some anemones in groups and some alone in tide pools? Sea anemones can reproduce in two different ways, asexually and sexually. Anemones are broadcast-spawners meaning that they release eggs and sperm into the water column for fertilization. However if you're an anemone that has settled onto a nice barren rock and don't have time to reproduce, but you want to prevent other anemones from taking over that rock you claimed, what do you? You split yourself through........ FISSION! This is asexual reproduction, where the anemone splits itself and creates another one of itself of the exact same genetic material.

Depending on species this process may take days to weeks, but once there are more clones present, more can divide themselves through fission. Sooner or later you'll see whole colonies of anemones on rocks!

Photo courtesy of Catarina Pien

In the intertidal zone one of the limited resources is space for sessile organisms so anemones have adapted a way to populate an area quickly . But what if that pesky neighbor anemone is also asexually reproducing right next to your clones? What would you do? That's when you take drastic measures, by fending them off with your acrorhagi, specialized stinging cells used to deter other anemones from taking over your area.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_jNwWQtLeY4

These battles are intense, both parties may suffer serious damage. As you can see in the video, the anemones when attacked retreat. This is because each one of those tentacles have stinging cells called nematocysts. Animals in the phylum Cnidaria (anemones, corals, jellyfish, and hydrae are part of this group) have these specialized cells.

There is a mechanism that triggers the release of this harpoon-like contraption, when released the harpoon penetrates into the target organism and releases the toxin which is useful to immobilize prey such as fish. If you've ever been stung by a jellyfish that's what exactly is happening; some species of jellyfish such as the box jelly and sea wasp have stings that cause excruciating pain, anemones also have these nematocysts too. However, because our skin is too thick for the nematocyst to penetrate into, you only feel a sticky sensation from touching anemones in the tide pools. The fact that we're immune to most anemone stings in the tide pools doesn't make it acceptable to touch them constantly though, the nematocysts do take quite a lot of energy for these anemones to regulate these mechanism. So the next time you're visiting the tide pools do the anemones a favor and just observe and be amazed at their adaptations for surviving in the intertidal zone!

Photo courtesy of Catarina Pien