By Catherine Drake, Invertebrate Zoology Lab

Have you ever heard of the Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary? If not, I bet you've stepped foot in the Sanctuary! If you've ever gone to the beach and stuck your toes into Monterey Bay waters (like many of our MLML graduate students have time and time again), you're in the Sanctuary! A National Marine Sanctuary is like a National Park or Forest, except that the protected area is underwater, starting at the high tide line. There are a total of fourteen Sanctuaries in United States' waters, including four along the California coast (from south to north): Channel Islands, Monterey Bay, Gulf of the Farallones, and Cordell Bank National Marine Sanctuaries. Like Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary (MBNMS), the other Sanctuaries were created to ensure that as we utilize the ocean's resources available to us, we also work toward sustainable practices and habitat protection.

MBNMS was established in 1992, in part thanks to the efforts of a grass roots campaign by Santa Cruz citizens who wanted to ensure that no offshore drilling would occur along this stretch of coastline, which is an essential area to both many different marine species and humans alike. It protects 276 miles of California's coast (almost 1/4 of our state's coastline!) and more than 6000 square miles of the Pacific Ocean and its inhabitants, and it stretches from San Francisco to Cambria.

Those of us living near the MBNMS are aware of its importance, but others around the globe may not be as informed. That's where "Big Blue Live" comes in - it's a production by the BBC and PBS, on August 31st to September 2nd at 8:00PM PT, and it will highlight all the amazing features of the MBNMS. The BBC has been filming here in the MBNMS for the past couple weeks, and will continue to throughout "Big Blue Live" to highlight all the amazing aspects of the MBNMS. Be sure to tune in to PBS starting tomorrow (KQED is our local PBS channel for NorCal) and check out the wonders of our Sanctuary!!

Some of our faculty members were consulted by the BBC for "Big Blue Live." Jim Harvey, MLML's director and marine mammal expert, and Dave Ebert, MLML's expert on sharks, skates, and rays, have served as information sources regarding natural history of these animals. Numerous specimens have been borrowed from our museum collection such as birds, whale bones, baleen and shark jaws. They've also borrowed our 3D model of the Monterey Bay and its submarine canyon. Dave Ebert has provided guidance on juvenile great white sharks that have been spotted in the area over recent weeks, and his student Catarina Pien has been a resource for elasmobranchs in Elkhorn Slough.

Take a closer look at the wonderful wildlife we met in Monterey Bay on #BigBlueLive: http://t.co/ROdLyh3Ley pic.twitter.com/2GT1ESuquS

— BBC One (@BBCOne) August 30, 2015

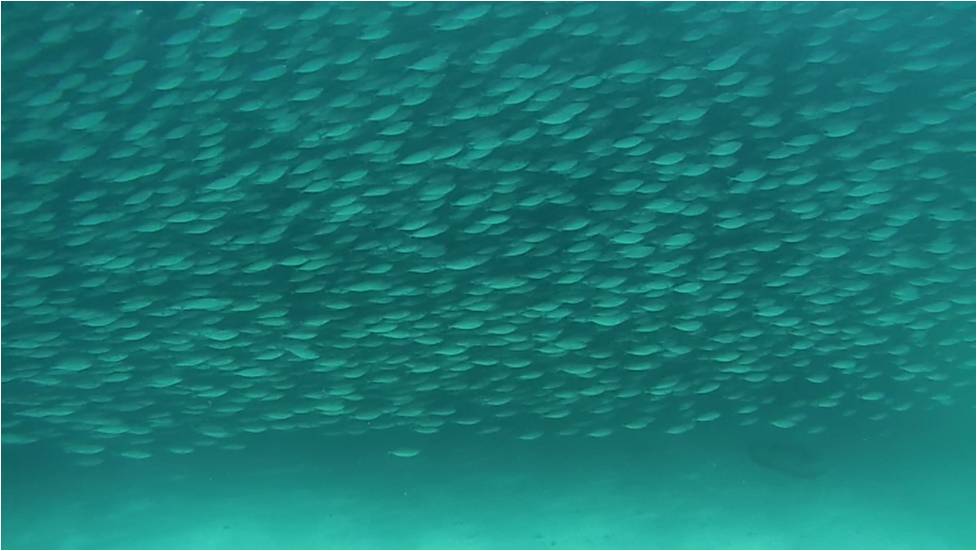

It's essential for us to understand the importance of the MBNMS, not only to protect its inhabitants - which include 34 marine mammal species, 94 different species of marine birds, about 350 species of fish and 450 species of algae, and thousands of invertebrate species - but also to learn from our past mistakes. Many of the animal populations are on the rebound from being hunted by humans in the past centuries.

Sea otters were hunted for their luxurious fur, which has one million hairs per square inch, and whales were hunted for their blubber for meat and oils that were often used in lamps that lined the streets. Local fish and invertebrates that we often enjoy at restaurants were also hunted without foresight into how the populations may suffer in the future. Now, with the MBNMS intact, all of these animal populations are on the rebound, thanks to a better understanding of sustainability and better fishing practices.

Us locals know how breathtakingly beautiful our Sanctuary is, and it's great that we're getting some global spotlight on the wondrous Monterey Bay. Thanks to the BBC and PBS, the videos of humpbacks breaching and sea otters eating clams will promote the central message of the Sanctuary, "To understand and protect the coastal ecosystem and cultural resources of Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary," to others globally. Hopefully "Big Blue Live" will attract visitors from all over who will recreate and enjoy visiting the Sanctuary while also understanding and respecting the history of Monterey Bay.

So, tune in to your local PBS station to watch "Big Blue Live" and to find out more about the MBNMS!

Below are a bunch of links about "Big Blue Live" for you to check out:

The BBC's "Big Blue Live" Facebook Page - Constantly updated with live footage from the BBC's film crew.

NOAA's MBNMS "Big Blue Live" Website - Information about MBNMS and it's involvement with "Big Blue Live."

PBS "Big Blue Live" Homepage - Has showtimes for "Big Blue Live" - check it out to find what time it airs in your location!

"Big Blue Live" Twitter - Live tweets about what the film crew is spotting out in the MBNMS.

Search Instagram's #bigbluelive - Photos from all the groups involved with "Big Blue Live."