By Drew Burrier

There are days that change you. One minute you are chasing what you thought was your dream, and then something comes along that changes your trajectory. Those days are rare, and can come to define one’s entire purpose in life.

For me that day was my first day at sea, working to unravel it’s mysteries aboard the R/V Pt. Sur. I had fallen in love with the ocean before, and knew that I wanted to become a scientist, but that day would come to change just exactly what aspect of Marine Science would become my life’s pursuit.

Prior to this cruise, whales and dolphins had dominated my interest in the ocean. They are charismatic and graceful, and inspire wonder in anyone able to view them in their world. I had been involved in research projects with these wondrous animals armed with a camera lens and a fast boat. So it was strange that a day at sea lowering instruments into the water and pulling them back up could supplant the sense of adventure I had already experienced. This particular cruise, however, was for the Physical Oceanography class that I had enrolled in at Moss Landing Marine Labs. Physical oceanography is the study of the physical properties of the ocean, or more bluntly, it is the study of how energy is put into and distributed in the global ocean. I had never considered it as a field I was interested in, or that it could even be an option for my career, but by the end of that day at sea, I new that I was not the same person that had left the dock. It turned out the mysteries that I was most interested in, that appealed to me the most were not the creatures roaming the depths, but the awe-inspiring forces that shape our planet.

Prior to this cruise, whales and dolphins had dominated my interest in the ocean. They are charismatic and graceful, and inspire wonder in anyone able to view them in their world. I had been involved in research projects with these wondrous animals armed with a camera lens and a fast boat. So it was strange that a day at sea lowering instruments into the water and pulling them back up could supplant the sense of adventure I had already experienced. This particular cruise, however, was for the Physical Oceanography class that I had enrolled in at Moss Landing Marine Labs. Physical oceanography is the study of the physical properties of the ocean, or more bluntly, it is the study of how energy is put into and distributed in the global ocean. I had never considered it as a field I was interested in, or that it could even be an option for my career, but by the end of that day at sea, I new that I was not the same person that had left the dock. It turned out the mysteries that I was most interested in, that appealed to me the most were not the creatures roaming the depths, but the awe-inspiring forces that shape our planet.

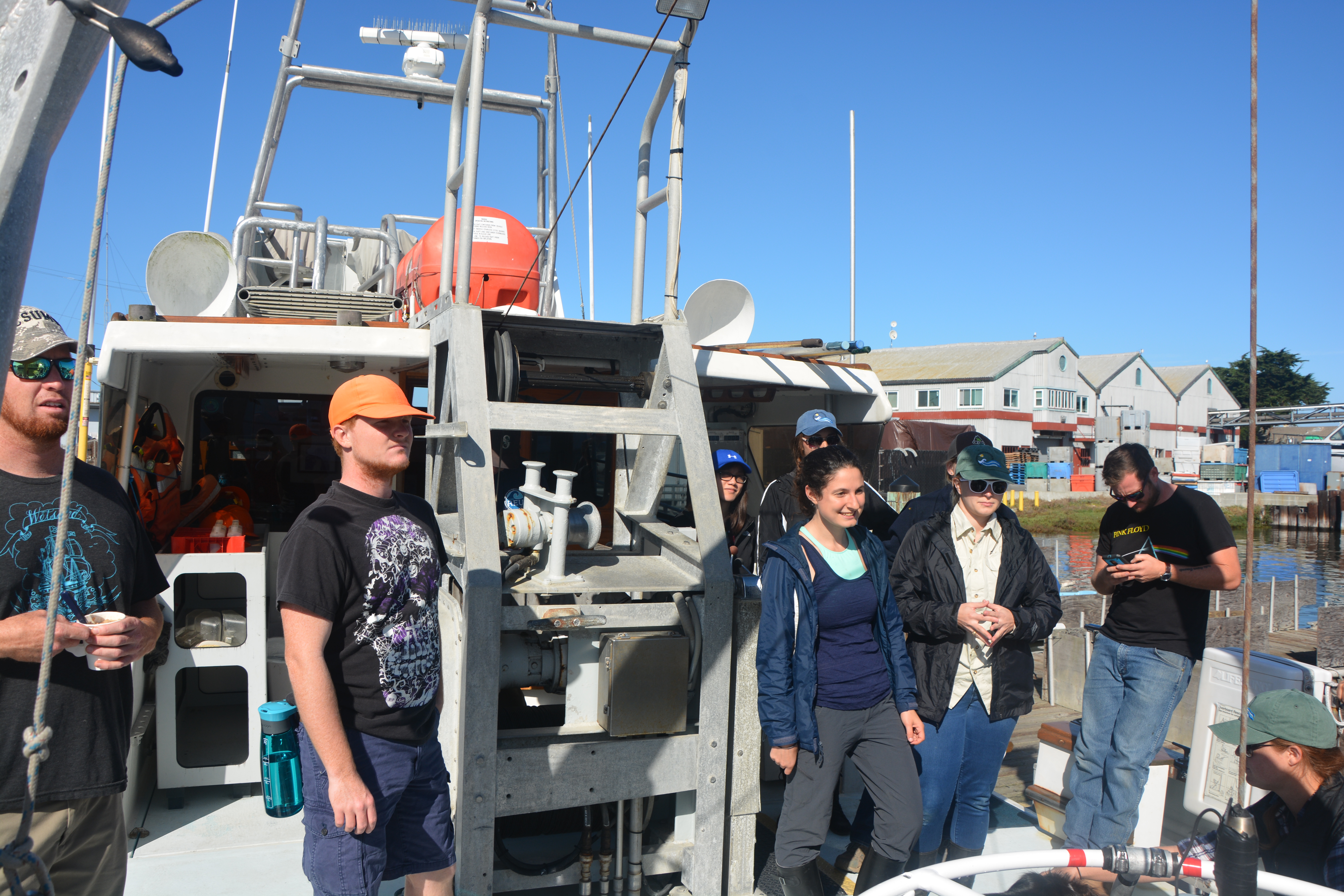

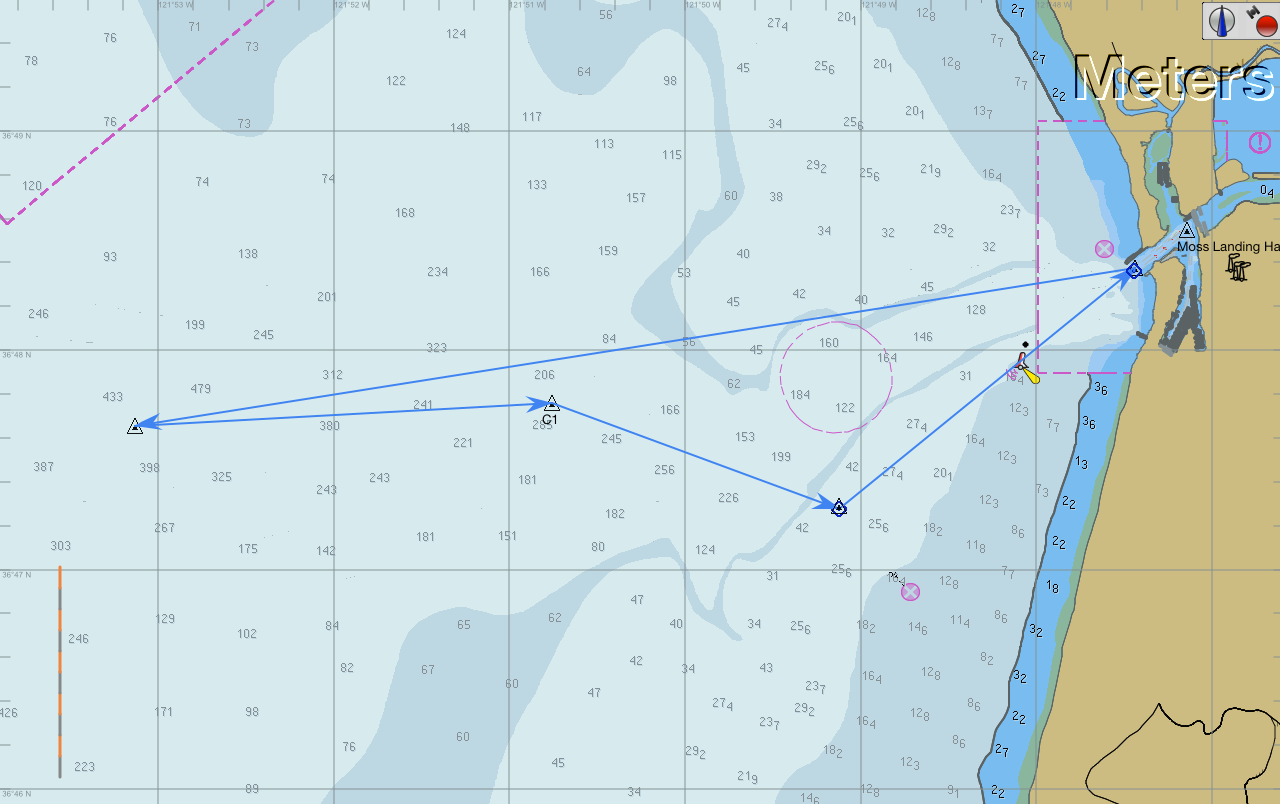

Last week I served as the Graduate Assistant for that same Physical Oceanography class and was able to observe the students in my class going through this same experience that had such a profound impact on me. The goal of this cruise was not simply to expose students to the joys of working at sea, but to hunt for elusive giants in oceanography: internal waves.

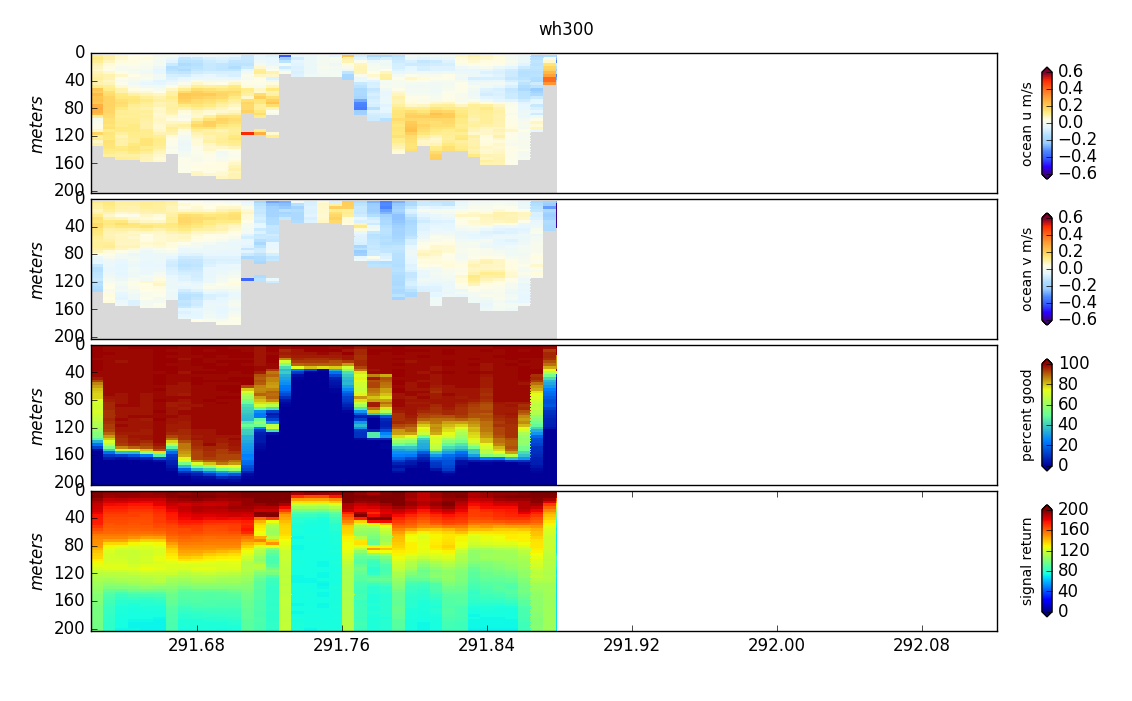

Internal waves are very similar to the surface waves you are most likely familiar with, with the exception that they oscillate within the ocean rather than at its surface, like the waves you may have surfed. The difficulty in studying these waves, however, is that they occur in parts of the ocean that are challenging to reach and require special instruments to be able to detect. One such suite of instruments is called a CTD (Conductivity Temperature Depth), which is lowered through the ocean via a winch and measures the key components of density in the ocean, namely temperature, salinity (extrapolated from conductivity) and pressure (depth). These properties are unique throughout the world ocean and determine how internal waves behave because just like at the surface, waves propagate along density boundaries. The second tool we use to detect internal waves is an Acoustic Doppler Current Profiler (ADCP), which in simplest terms is an underwater speaker and microphone that makes a sound at a known frequency (pitch) and then listens for the return signal. The change in that pitch is related to the direction and speed that the current the sound wave passes through. You’ve undoubtedly experienced this if you’ve ever been standing still when a truck passed you blaring its horn. The sound at the truck is never changing, but since it is moving away from you, you perceive a pitch change. As internal waves pass the ADCP the velocity of the water at various depths tells us a lot about the characteristics of the internal waves.

As I watched my class donning life jackets and hard helmets, fighting the roll of the ship and the occasional wave spilling over the aft deck, straining to guide the heavy instrumentation on and off of the deck, wet and tired but undaunted, I couldn’t help but return their beaming smiles. Working aboard an oceanographic vessel is no simple feat, but for some reason nobody ever sees it as work. Not the first time, and not the 1,000th. It is an endless adventure that will continue to reward the persistent. I can certainly appreciate that not everyone gravitates to the field of oceanography as I have. But I can say with confidence, having seen it in the eyes of my students, that there is something universally magical about one’s first research cruise. I experienced it and it changed my life. The beauty of this field is that, there’s always something new to learn and experience.