Marine and Green

By Jackie Lindsey, Vertebrate Ecology Lab

Happy St. Patrick's Day from all the critters wearing green under the sea!

Florida manatees swim so slowly (3-5 miles per hour) that they can accumulate an algae coat on their skin.

Happy St. Patrick's Day from all the critters wearing green under the sea!

Florida manatees swim so slowly (3-5 miles per hour) that they can accumulate an algae coat on their skin.

It was just announced a couple months ago that researchers in New Zealand found a specimen of the hydroid Protulophila that was previously believed to be extinct for 4 million years. Before this discovery, these organisms had only been found in fossil records in the Middle East and Europe, some of which dated back 170 million years.

Awesome discovery, right? But to take a step back now, what exactly is a hydroid?

It's a Cnidarian, which is a phylum of aquatic invertebrates; other cnidarians include corals, sea anemones, and jellyfish. Through their lifecycle, cnidarians have two basic forms: (1) a polyp that is sessile and attached to a substrate, and (2) a free-swimming medusa.

The fossilized symbiotic hydroid was found inhabiting the tube of a one-million year old serpulid tube worm fossil in Wanganui, New Zealand. Because they are found within fossilized rocks, these cnidarians have been deemed "living fossils." This finding gave the researchers an idea: maybe the hydroid could be found alive somewhere in New Zealand waters.

Sure enough, the scientists examined samples taken from Picton, NZ that were collected in 2008 and found preserved Protulophila specimens. Dr. Dennis Gordon, one of the scientists involved in the finding, says, "Finding living Protulophila is a rare example of how knowledge of fossils has led to the discovery of living biodiversity."

He also said that "Our detective work has also suggested the possibility that Protulophila may be the missing polyp stage of a hydroid in which only the tiny planktonic jellyfish stage is known. Many hydroid species have a two-stage life cycle and often the two stages have never been matched. Our discovery may thus mean that we are solving two puzzles at once.”

One of the great things about being a student at Moss Landing Marine Laboratories is going diving with your fellow students. You get to see what they are studying and hopefully get some good karma or pay them back for helping you out. I was able to get back in the water after a couple months of drying up on land and dive with Devona Yates.

She is interested in predator-prey relationships and how predatory fishes can have cascading effects on lower trophic levels as they consume invertebrate prey. This cascading effect may differ inside and outside Marine Protected Areas (MPAs), as it appears MPAs may have different, larger, and more abundant predatory fish. Devona is using tethering and survey methods to quantify mortality of these invertebrates and how that may vary as a function of MPA status. It will be interesting and exciting to look at these MPA effects on the survival of these important prey sources for fishes. We use MPAs as a way to protect and increase important ecosystem members we depend on for food and are necessary for maintaining ecosystem function. Predator depletion and recovery may cause changes that were much more complex than we had thought.

(LOOK) Here is a link to a short video clip of the dive, even harbor seals are interested in science.

This past weekend, Moss Landing Marine Labs opened our doors and welcomed everyone to our annual Open House event. For those of you new to Moss Landing traditions (as I am as a first year student), it is an event we hold every year in the Spring that is organized by the student body and hosted by the students, faculty, and staff.

We take Open House as an opportunity to share our research in a fun, yet educational way. Just to name a few exciting activities: the Invertebrate Zoology and Molecular Ecology lab had an invertebrate touch tank where you could see, touch, and learn about all of our interesting local invertebrates.

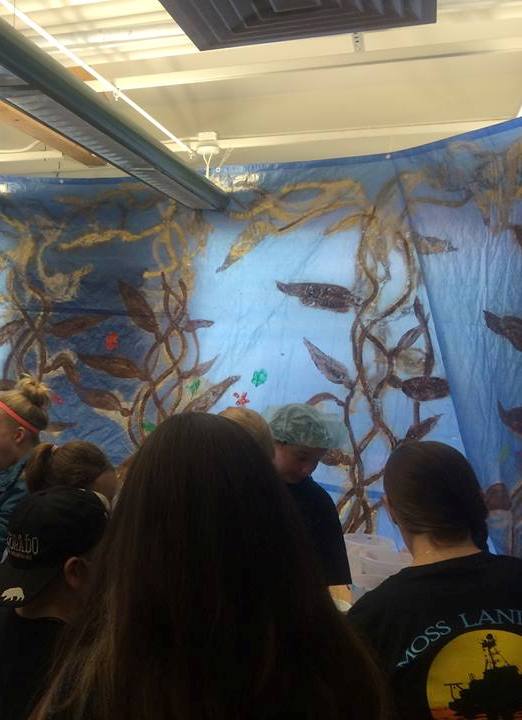

The Phycology (algae) lab allowed you to walk through a painted kelp forest and learn about the foods you eat that contain algae, such as ice cream and pudding.

Our diving program even offered the opportunity to get suited up like you were going on a dive and to see how some of the S.C.U.B.A gear works!

And there was even a chance to tour our retiring, R/V Point Sur.

Though Moss Landing Marine Labs hosts the event, it would not be what it is without all of the support we receive from those that contribute to and attend the event. We raised over $10,000 in scholarship money, made possible by the generous contributions from our donors and the ~2,500 people that attended Open House!

To everyone who worked so hard on planning and running Open House, and everyone in our Moss Landing community and beyond, thank you!

It is amazing how many different ways organisms can survive in the ocean. One of the most interesting is the many different strategies to try to get food from the water (filled with phytoplankton, zooplankton and detritus (particles of decaying algae and animal material)), from larger algae growing on the bottom, or from the organisms that consume these sources.

We see Kelp Rockfish associating with, surprise...kelp! They eat different crustaceans on the kelp and even eat small year-old rockfish.

This impressive Lingcod is a predator around the kelp forest, they eat invertebrates like squid and crustaceans and many different fishes.

This impressive Lingcod is a predator around the kelp forest, they eat invertebrates like squid and crustaceans and many different fishes.

This Fish-eating Anemone eats crustaceans and fishes. It would not be pleasant to be captured by one of these and digested slowly!

This Sunflower Star is a surprisingly fast moving predator in the kelp forest. They, like other seastars, extrude their stomach and digest their prey using acids, another not-so-fun way to be eaten.

This beautiful Kelp Greenling male eats different invertebrates and even fishes when they become available.

This lined chiton moves along the bottom scraping the surface, getting foods like coralline algae, detritus (decaying algal and animal material), attached invertebrates, diatoms (algae), red algae, and green algae.

These species are just a preview of what we see each dive around the Monterey Bay area. I am grateful people before us have studied these organisms so we are able to construct food webs to try to understand how all of this diversity we see interacts over time and space.

Circulating seawater systems are very important for marine laboratories as they need to keep organisms from the ocean alive and use the water to aid in conducting experiments. We have recently had our Moss Landing Marine Laboratories offshore intake upgraded and we went on a dive to inspect its current status. The large meshed cylinder sucks in water and supplies our lab with flowing seawater. We routinely inspect and clean the surface of the grates and the structure.

It is interesting to see what invertebrates recruit or move onto the structure. With sand surrounding us we create a small oasis of life concentrated on the hard substrate. One of the issues we have to deal with is that seawater contains invertebrate larvae and some species will settle on the inside the pipes and eventually constrict and clog our flow, similar to plaque buildup in an artery. We have to force a Pigging Inspection Gauge (PIG), a tool which is usually a piece of cylindrical foam, through the inside of the pipe to clean and clear the walls. It's great we can get routine cleanings so our seawater system continues flowing and our lab doesn't have a "heart attack"!

By Jarred Klosinski, Phycology Lab

If you’re like me and take long walks on the beach, you may have noticed more mounds of algae along the shore. These mounds are called beach wrack and can contain kelps as well as seagrasses. Other types of seaweeds including red and green algae are also found, but not as often.

Recently the marine science diving class here at Moss Landing Marine Labs went down to Monterey's Breakwater to conduct a sunset and night dive. The first dive was to a rocky outcrop called the Metridium field. The Metridium are white plumose anemones that look like fluffy cauliflowers and filter particulates out of the water. It is a stunning sight with so many anemones.

The second dive was conducted by nightfall. Every diver had a glow-stick to better locate their buddy and stay in visual contact in the dark. Each diver has a waterproof light, it takes practice to communicate underwater let alone now using a flashlight. We saw different species like red octopus which were out foraging and rockfish that seemed to hover almost half asleep in the water column. It is interesting to see these changes that happen as the rocky reef changes from day to night.

This time of year offers the chance to provide a romanticized explanation of autumn on the central coast. I could explain how here at Moss Landing the weather is turning colder, the leaves are changing color, and the storm clouds bring a scented promise of the rains to come. However, we have more important things to discuss: Halloween!

This past weekend was Moss Landing Marine Labs’ annual Halloween Party. Everyone came in costumes and as part of the tradition, each lab or group brought their pumpkin to be judged by the student body in the pumpkin carving contest. Though officially there was only one winner, I think everyone did a great job. What do you think?

Photo Credits: Catherine Drake

Halloween, however isn’t just about carving pumpkins, it also calls for sweet treats and telling tales of the unusual and scary! Ghosts, ghouls, and goblins may be the usual topic of conversation when talking about things that go bump in the night, but my favorite scary creatures to discuss are those truly unusual, and of course, found in the ocean!

One of my favorite “scary” species is the Goblin Shark. Though it is no threat to humans, as it lives very deep, those jaws are a bit spooky!

Another favorite spooky creature of mine is a Bone Worm. These worms feed on skeletons of dead whales! How’s that for an evolutionary adaption?

And last, but certainly not least is the Blobfish. While in water the blobfish has a fairly normal appearance, but out of water – due to low tissue density – its appearance is a bit unusual!

Happy Halloween!

Earlier this week I volunteered to dive on the MLML seawater intakes, located about 200 m due west of the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute (MBARI) and 17 m below the surface. The intakes supply seawater to multiple sites around Moss Landing, including the aquarium room at MLML, the Test Tank at MBARI, and the live tanks at Phil’s Fish Market.

The purpose of the dive was to attach a surface float to a subsurface float located at a depth of about 15 feet. A secondary objective was to visually inspect the intakes, which can be viewed in the video below.

So how do you find an intake system 50 ft below the water?

To execute the operation, Assistant Dive Safety Officer Scott Gabara and I took a whaler from the MLML Small Boats with the assistance of boat driver Catherine Drake. We used the best GPS coordinates previously called upon to locate the intakes, then threw a spotter surface float attached to a line and weight that unraveled to the seafloor. We followed that line to the bottom and practiced our circle search skills until we found the first of the two intakes. While anchoring the search line I saw a pipefish, a couple flatfish, and not much else. During our descent and ascent we spotted half a dozen sea nettles, but on the sandy bottom it appeared pretty desolate. The intakes, on the other hand, provide a hard substrate for sessile invertebrates and their predators to form a lively little oasis in the sand. The first thing you notice when you come upon the intakes are the large white Metridium anemones. If you take a closer look at the video, around 15 seconds in, you can spot a little octopus scurrying for cover. After inspecting the first intake we moved to the second, that’s right, completely submerged by sand, with the line extending up to the subsurface float. Though the video is short you can see some of the organisms residing on the line include seastars, Metridium, caprellids or “skeleton shrimp”, and my favorite marine invertebrate: nudibranchs. Hermissenda (opalescent) nudibranchs, to be exact. I wish I had a chance to take still photos while I was out there, but we had a job to do. We successfully tied the surface float to the line and removed old line, thus making it much easier for future divers to study sediment movement and perform maintenance on the intake pipes.

I'll admit had another motivation for volunteering for the dive. Beyond helping out and increasing my scientific diving experience, I was curious about the system. In 2011 and 2012 I worked as a research assistant for CeNCOOS, and helped maintain the oceanographic instruments at the MLML shore lab and ensure that the public data portal was operational. That system is dependent upon water flowing in from the intakes. I learned even more about the seawater system in my chemical oceanography class, so it was really cool to see the pipes from under the sea. The visibility for most of the dive was much better than it seems in this video, as we spent most of the time working further up in the water column away from the fluffy layer composed of detritus and fine-grain sand.

When my dive buddy and I returned to the surface we met back up with our boat, reeled in the line for the first float, and cruised back to the harbor. Another day, another successful dive!