by Erin Loury, Ichthyology Lab

There’s nothing like seeing the food-chain in action to make you appreciate how important eating is in an animal’s life – and why it’s so important to study (says the fish guts girl)! For many things in the ocean, it’s just a matter of time before they become something else’s lunch. It’s a fish eat fish world out there!

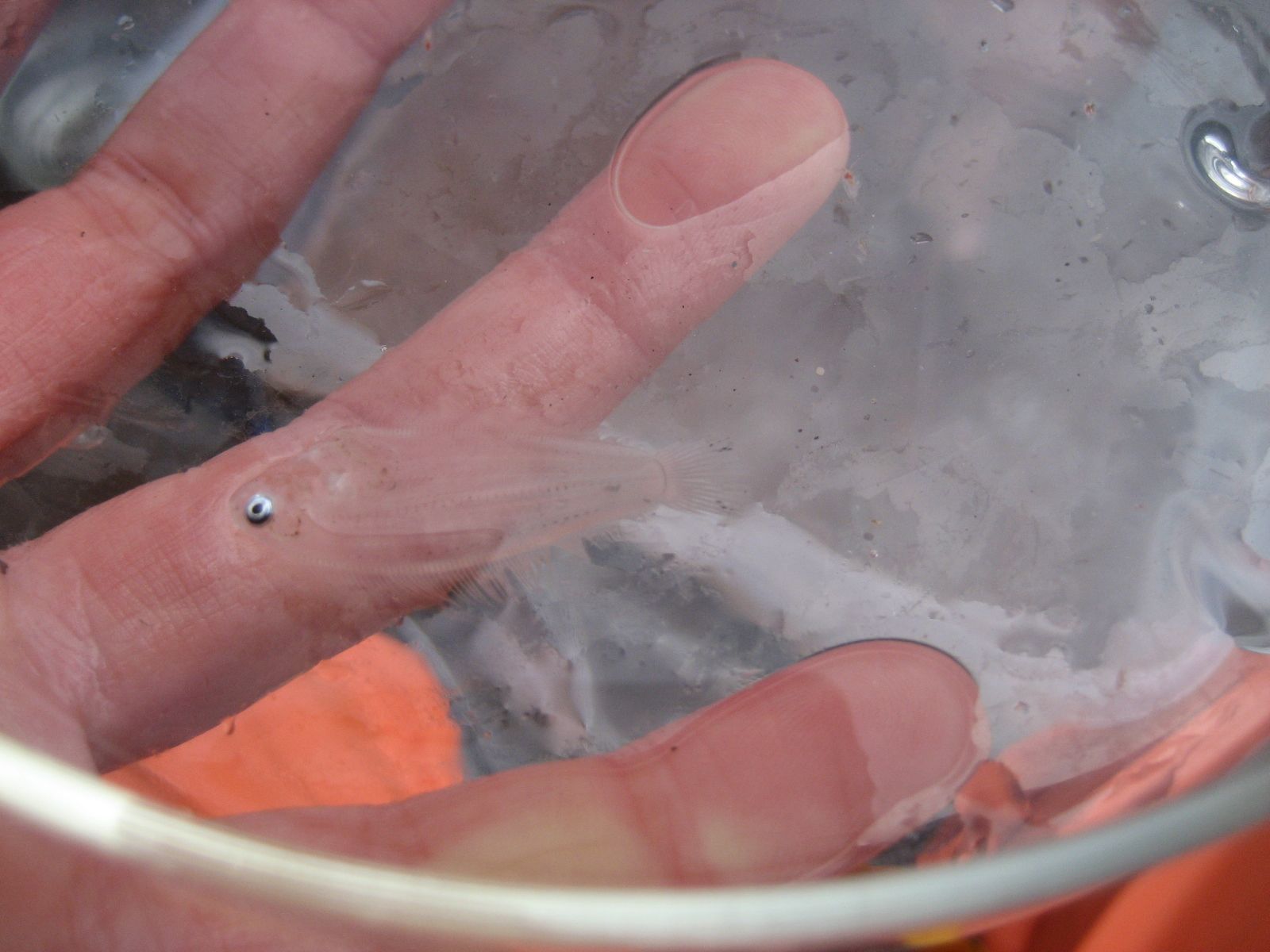

This week’s photo comes from summer surveys I participated in with the California Collaborative Fisheries Research Program while we surveyed new marine protected areas in central California. The photo is of a lingcod, and shows off the feature that is probably most important to appreciate when working with these fish – TEETH! Those are a clear indication that this fish is a predator, and it means business!

What you see in its mouth is the tail end of a hapless rockfish experiencing the ultimate “game over.” This particular lingcod ate the rockfish right out of the fish trap that both were caught in, but are also big predators on rockfish in the wild too.

Chances are you’ve probably eaten rockfish or lingcod yourself if you live in California – meaning this photo really shows three levels of the food chain – rockfish, lingcod, and humans. Humans are probably the most voracious predators of all in the marine environment, emphasizing the need to appreciate what we eat, and what it eats in turn! So the next time you get that fish taco or fish and chips, think about how you are taking part in the bigger ocean food chain.