By Jamie Sibley Yin

Dr. Valerie Loeb is an adjunct professor at Moss Landing Marine Labs. Currently, she functions as an independent Antarctic ecosystem research scientist collaborating with Jarrod Santora of UC Santa Cruz. In April, she headed out to sea with a new NSF funded project entitled “Pilot Study: Addition of Biological Sampling to Drake Passage Transits of the ‘LM Gould'”. The following are updates from the field by Jamie Sibley Yin who is in charge of communications.

05/02/15 - Fish for Days

We are on another fishing trip. We left a day early from station because the seawater pumps failed in the Palmer Station aquarium and all the fish died. It was tragic, and the need for more fish was urgent. Since this leg of the cruise was dedicated to the fishing group, and we were not sampling, I was left with little to do and so helped with the fishing efforts. This included deploying the pots and trawling.

First we deployed the pots, which are left out for 24 hours. We had to prepare bait for the bait bags that lure the fish into the pots. The bait is hung on the mesh inside of the pots by large, industrial safety pins. The irresistible smell of slightly rotten fish lures the Notothenia coriiceps (one of their target fish) into the metal pots. I use a large kitchen knife to slice mackerel and sardine into chunks. The partially frozen fish are easy to chop but some of the fish have thawed, instead of creating firm bite size pieces of fish, my knife mashes them, brown guts ooze onto the plywood I’m using as a cutting board.

First we deployed the pots, which are left out for 24 hours. We had to prepare bait for the bait bags that lure the fish into the pots. The bait is hung on the mesh inside of the pots by large, industrial safety pins. The irresistible smell of slightly rotten fish lures the Notothenia coriiceps (one of their target fish) into the metal pots. I use a large kitchen knife to slice mackerel and sardine into chunks. The partially frozen fish are easy to chop but some of the fish have thawed, instead of creating firm bite size pieces of fish, my knife mashes them, brown guts ooze onto the plywood I’m using as a cutting board.

Over 100 lbs of fish later, and the bait bags are done. The marine technicians (MTs) load them into the pots. The pots are then lined up on the back deck of the ship in preparation to be pushed off into the water. They are kept close together in their groups of four, the rope that links them together is coiled atop each one. We move them as a unit, which means four people need to move them at the same time. It takes all my body weight to shove the pot across the deck into the line. They are pushed into the water by the MTs, we will retrieve them in a day.

The LMG Olympics are here, aka time to pull in the fish pots. Deploying them is pretty straightforward but pulling them up is a whole other kettle of fish. It takes six MTs and four scientists to coordinate the reeling in, and unloading of the pots. The boat gets as close to the pots as it can and then drifts towards them. Once the head MT, Jack, thinks the boat is close enough, he takes a four-pronged hook and lassos the buoy. The buoy has a GPS on a pole attached to two large orange balls, which are in turn attached to a set of pots. There are four sets of pots--16 in total. The buoy and balls are hauled onto the deck, coils of blue rope are reeled in and set aside. The 1st pot comes up, it’s full of fat Nototheniids, their pectoral fins splayed, trying to stabilize themselves as we roll the pot over the deck, their mouths agape as they gasping for water. Kristin, one of the PIs, unlatches and rips open the pot and hands me a wriggling fish. Its’ whole body flops in protest, mouth wide, I hold it like a baby and walk swiftly to the aquarium room where I drop it into one of the tanks.

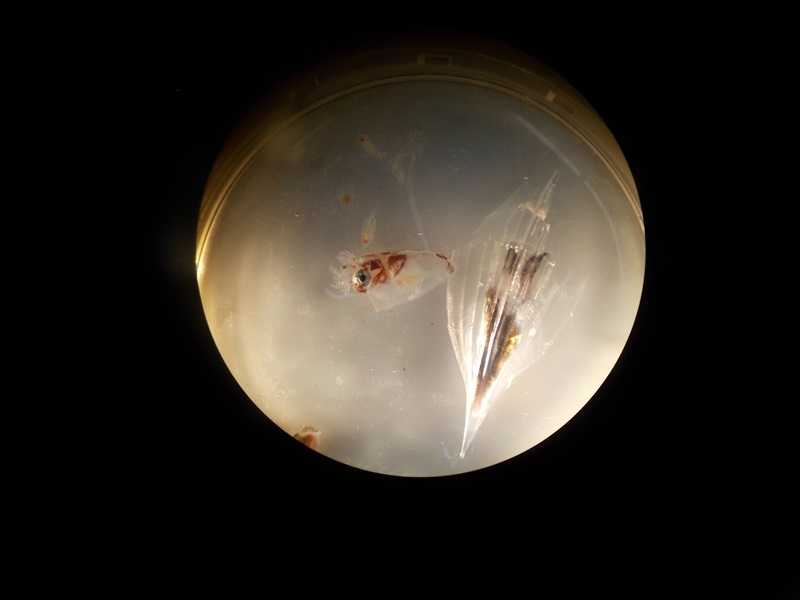

Trawling is exciting because of the sea life that is pulled onto the deck from the ocean depths. Hundreds of sea stars, milky white octopuses, bryozoans, sea cucumbers, wriggling spiky amphipods, gelatinous tunicates—my eyes can’t pick out everything in the tangled squirmy mass hauled on to the deck. I go to bed as images of sea spiders and mystery fish flash through my mind. I could have spent hours picking through the by-catch, commanding the creatures to identify themselves.