by Angela Szesciorka, Vertebrate Ecology Lab

Most of my posts tend to reflect my love of marine mammals, specifically the large, “charismatic whales” as they are oft referred to.

But I wanted to tell you about one of my day jobs. [As if grad students have all this time in-between taking classes and working on their thesis. But I digress … ]

I work for a marine engineering company in Santa Cruz, doing coastal engineering. Or, what we tell the general public: we play with mud.

Coastal engineering is a sector within civil engineering. This means companies hire us to help them with harbor design and construction; beach nourishment and erosion studies; wave modeling and forecasting, sediment transport modeling; and dredging and pile driving monitoring; among many others.

My jobs with this marine engineering company have largely centered on acoustic monitoring, water quality analysis, and sediment analysis. It may not sound terribly glamorous, but I get to do really cool hands-on field science.

Some days are spent outside at the Moss Landing Harbor basking in the sun; chatting with salty sailors; and monitoring pile drivers and dredgers to make sure that their activities are not causing excessive water and noise pollution in an area where marine birds and mammals congregate to forage and rear young.

Usually I have to battle not to get distracted by the many vivacious otters, harbor seals, California sea lions, gulls, cormorants, shore birds, and the occasional mola that employ the area.

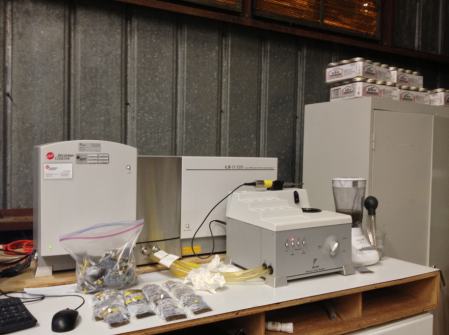

Other days I work in a secluded (and freezing!) lab with my particle size analyzer, handy blender, and of course, the many Whirl-Pak bags full of sediment.

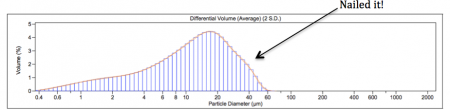

I’ve analyzed possibly more than 1,000 samples since December. Tedious? Sometimes. But interesting. Especially when you nail the analysis.

I learn cool terms like Atterberg limits, which is a basic measure of the nature of a sediment or soil (solid, semi-solid, plastic and liquid), and I bake sediment in a 500 degree Celsius oven for 'loss on ignition' to estimate the amount of organic and carbonate content in the sediment.

I also recently found out that we have two of the three only privately owned Sedflumes in the world, which we use to measure erosion rates and critical shear stress — especially useful for analyzing contaminated sediment in rivers, lakes, and estuaries.

OK, OK. Before you find you get bored with all this sediment talk, just know that there is a wealth data here. I am told our lab has enough data for a master’s or Ph.D. thesis project if any one is so inclined.

Must love modeling. And mud.

I also just want to recommend that you keep an open mind when it comes to pursuing science work. Since I started working here, I have learned tons of new field techniques and made many new professional connections. I also have access to field equipment that I wouldn’t otherwise. So get out there and do some science even if it's not with your specimen of choice!