by Colleen Young, Vertebrate Ecology Lab

In my last post I told you about the findings of my thesis research on the effects of vessels on harbor seals (that cruise ships caused the most disturbance of all vessels), but then left you hanging about what the findings mean and why anyone should care. So now that you’ve had a chance to think about it, what do you think?

Well, finding that cruise ships accounted for a greater incidence of flushing (when seals leave the ice and hit the water) was not what I expected, based on previous studies, which found that kayaks and canoes (non-motorized vessels) caused greater disturbance. However, these previous studies were conducted at terrestrial haulout sites, where the water depth near the harbor seals is extremely shallow, making it easy for non-motorized vessels to get close to seals, and difficult for motorized vessels.

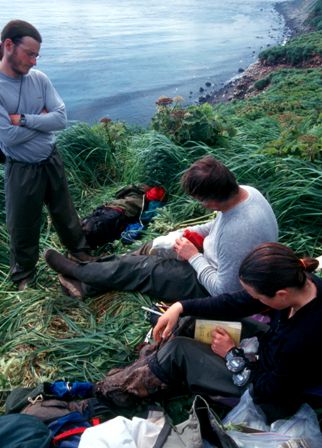

In Johns Hopkins Inlet, however, seals haul out on floating icebergs in a deep fjord, so motorized vessels can get very close to seals, whereas kayaks stay more distant. Therefore, the differences between reactions of seals to different vessel types may actually be a response to how close the vessels approach. I tried teasing apart the effect of vessel distance on harbor seal behavior, but that proved less straightforward than I anticipated. That’s because, like humans, harbor seals have individual personalities, meaning that they respond differently to approaching vessels, making their behaviors difficult to predict.

So harbor seals are disturbed by cruise ships and motorized vessels more than kayaks. So what? Well, harbor seals numbers in Johns Hopkins Inlet have been decreasing since 1992. In contrast, cruise ship numbers in Glacier Bay National Park have increased, meaning the potential for disturbance is greater than ever before. Harbor seals are top-level predators, so they exert great influence over marine ecosystems through the food chain. Therefore, it is important to protect harbor seals, including reducing disturbance, in order to maintain a healthy ecosystem in Glacier Bay.

I made some recommendations to the resource managers at Glacier Bay National Park about how they could reduce disturbance to harbor seals by cruise ships. I recommended that they teach boaters about how to avoid disturbing harbor seals by keeping a good distance and not approaching seals head-on. I also recommended that they limit the number of motorized vessels allowed to enter Johns Hopkins Inlet, and have disciplinary action for boaters who disturb seals.

I was able to voice my recommendations to the park superintendent and other important decision-making people at a special conference. It felt really good to know that the people who have the authority to protect these harbor seals wanted to hear what I had to say and were interested in implementing many of my suggestions. I hope to go back to Glacier Bay some day to see how the harbor seals are doing.