How DO marine ornithologists catch the birds they study? Sometimes, it’s just like catching fish!

Of course, first you’ve got to find the birds. The oceans are HUGE expanses. They can be difficult to navigate, and birds can fly literally hundreds of miles in a single day! Luckily for biologists, the most predictable place to find seabirds is actually on land, on a breeding colony during their reproductive season. So, how does a biologist catch a seabird while it’s on a colony? Amazingly, many seabirds exhibit no instinctual fear of humans while on their breeding colonies, and if they nest on flat ground then researchers can simply walk right up and touch them!

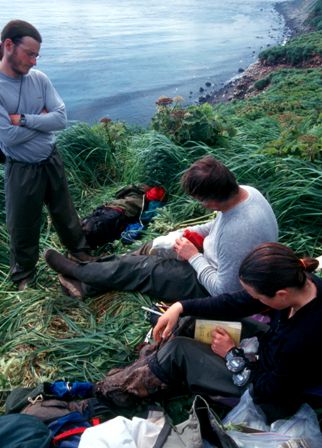

In many places where birds nest on cliffs they also exhibit little fear when humans lean over from the top, just a few feet above them. This allows biologists to employ a modified “fishing” pole, with a slip-knot noose, to grab a bird (loosely!) by the neck, nudge it off its perch, and gently guide it through the air (as it flaps in a startled flurry!), back up to the cliff top where measurements, blood draws, and other work can be done.

How can it be that these animals, which routinely fly thousands of miles in a year, would just sit there and allow themselves to be captured on their breeding grounds? Wouldn’t this lack of caution put the breeding birds at great risk of predation? Yes, but… many seabird colonies are located on relatively small and terribly remote islands, and in prehistoric times, as the birds evolved their breeding habits and reproductive strategies, there were NO land predators whatsoever! This is because many of these remote islands emerged as the tops of ancient volcanoes, which oozed and spewed and built their way straight from the depths of the oceans, and so were never associated with any parent land mass.

As such they remained for eons in isolation, free of any land predators. Seabirds find these types of islands particularly suitable for breeding. Without many foreign disturbances, they are left to partition the breeding habitat amongst themselves to a maximal extent. Often, this means some VERY dense nesting aggregations!