By Michelle Marraffini

Invertebrate Zoology and Molecular Ecology Lab

With continued global expansion of humankind and climate change, how will native communities be affected by introduced species? Recent state surveys identified at least 312 non-native species in California coastal waters, many of which are known to have strong negative impacts on shipping, recreational and commercial fishing, and native habitats and local species (CDFG, 2008). Factors regulating the success of non-indigenous species are of interest to scientists and managers.

Artificial habitats like floating docks and pontoons act as ground zero for newly arrived non-indigenous species. These species arrive though many mechanisms, such as ballast water and fouling on the bottom of boats; we heard all about ballast water from fellow MLML student Catherine Drake, The Ballast Water Balancing Act. Species that settle in marinas and harbors can than travel along the open coast and into estuaries, where they may outcompete native species for resources and become dominant on human structures such as water pipes, sewer grates, and aquaculture cages.

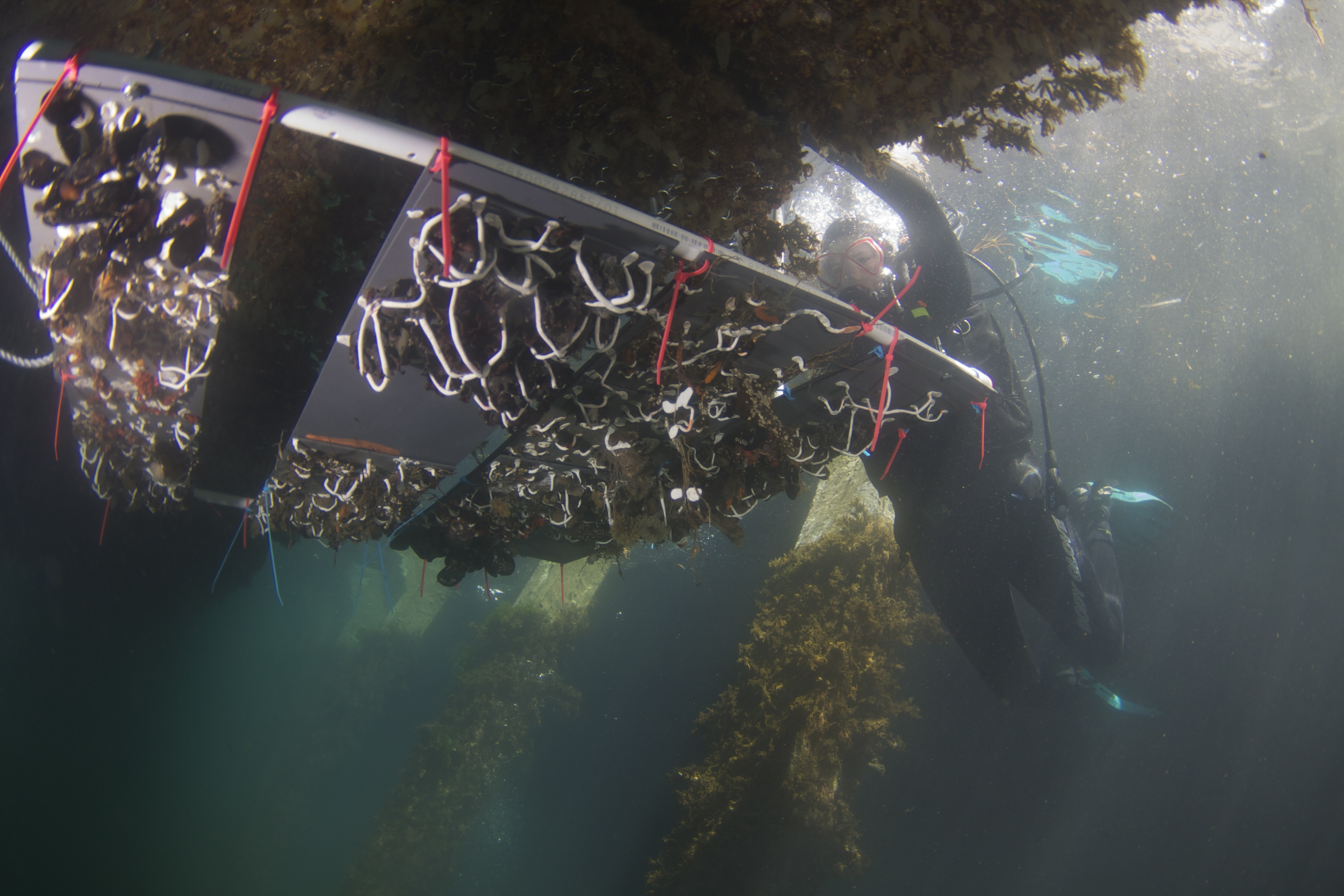

Under the floating docks of Monterey Harbor animals are battling for space. For my thesis at MLML, I am studying the role of native invertebrate species on invasion success. I will look at the sessile invertebrates like tunicates (Phylum Chordata), mussels (Phylum Mullusca), bryozoans (Phylum Byrozoa), hydrozoans (Phylum Cnidaria), feather-duster worms (Phlyum Annelida) and anemones (Phylum Cnidaria). By making experimental treatments that vary the number of species, the amount of native verse non-native species, and the amount of open space in artificial communities hopefully I can untangle part of the story about how non-native species become established.

Take a look under the dock as the battle is under way and stay tuned for the winner!