By Grace Teranishi, MLML Ichthyology Lab

By Grace Teranishi, MLML Ichthyology Lab

⧪ Salinas, CA (Summer 2020)

By now we’ve grown somewhat accustomed to the haze and the smell of smoke, the ash that dusts our cars, our patios, our coats. It’s August, night. My friends have invited me over to drink beer and observe the glare of the River Fire ebb and flow over the hills across the highway. Within the week they’ll receive an evacuation order.

With both COVID-19 and environmental crises to convulse the world, this past year has witnessed its fair share of fires—literal and figurative—disrupting homes, livelihoods, social norms, and mental stabilities. Unsurprisingly, we find increasing evidence of how one pandemic (COVID) interacts with and bears resemblance to another, even deadlier one: climate change.

On one level, we see a troubling link between COVID and climate change due to the role the latter plays in the spread of diseases in general. Rising temperatures can foster conditions ideal for particular diseases to thrive, while climate-induced habitat loss and species migrations can increase human-animal interactions and subsequent risk of pathogen transmission. Combined with booming population growth and livestock crowding, we have more people in contact with animals than ever before.

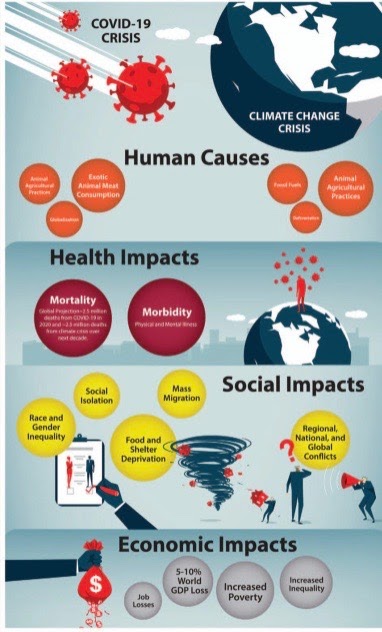

Moreover, even if we cannot draw a line directly between anthropogenic (human-caused) climate change and the current COVID-19 crisis, we still find instances of how the two interact dangerously. According to a recent study, people exposed to higher levels of air pollution may also be more likely to die from COVID. Another study from this year reported that the whale watching industry is vulnerable to both climate change and COVID-19 (climate change affects migration patterns; COVID affects tourism), and could take decades to recover. Although these two examples seem to have little in common, they both illustrate that our two pandemics can exacerbate one another’s harmful impacts on individual, economic, and social health.

Another level of connectedness between our global health emergency and environmental emergency lies in the many parallels they share. Both disasters:

- Generate social impairment and housing instability

- Disproportionately harm vulnerable populations and low-income communities

- Require widespread action to Flatten the Curve

- Spread exponentially through rising globalization and international travel

- Reduce the United States’s GDP (gross domestic product) in the long run by similar amounts

- May be mitigated by urgent action

- Are extremely deadly

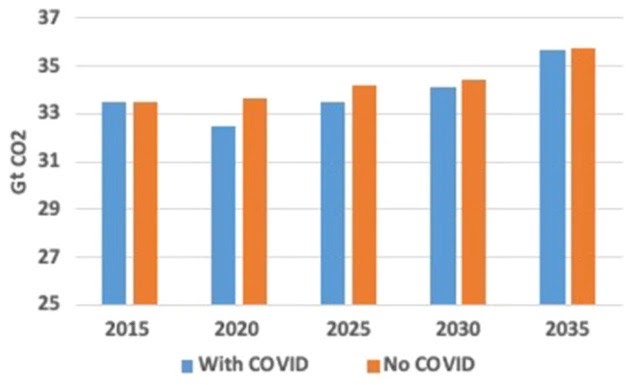

To date, nearly 3 million people have died of COVID-19 worldwide. If emissions continue to rise at current rates, climate change’s death toll will surpass this number many times. The perils of climate change are hardly new news, yet the COVID shutdown inadvertently led to the greatest reduction of carbon dioxide emissions the world has ever experienced in a 6-month period.

Unfortunately this dip amounts to a negligible impact in the grand scheme of ever-growing climate threat, and initiating the same level of widespread action to combat the climate change pandemic that we witnessed during the fight against the COVID pandemic remains challenging; daily death tolls and personal losses bear far more immediacy to folks than a degree of Celsius or a meter of sea level.

Following travel restrictions and our global shutdown, we temporarily witnessed record-breaking reductions in carbon dioxide emissions. Source: www.carbonbrief.org

Even so—though travel restrictions and shelter-in-place orders had little direct impact on global climate—we still may find some hope in the lessons that the COVID-19 pandemic has taught us about climate change. For one, we at least caught a glimpse of the possibility that relatively unified, effective, global-scale change is in fact possible. While we might not be able to sustain an eternal lockdown, we can start to take more drastic measures to reduce emissions. In fact, many regions have begun doing so. COVID-19 wreaked havoc on the global economy. While this alone is undesirable, the lowered GDP corresponded to lower greenhouse gas emissions and has made reaching our goals more feasible, thus opening up the possibility for more ambitious targets. In the Age of Zoom, we have also collectively learned new effective strategies for working from home and reducing unnecessary travel. Yet another environmentally friendly outcome has been a disruption of international supply chains: masks and other products we used to source from other countries we now produce more locally due to high demand. With business-not-yet-as-usual, we have a unique opportunity to rebuild to a greener normalcy.

At the very least, the chaos of a global health crisis may have opened many eyes to the fact that we ought to treat our environmental crisis with the same urgency (we’ve now seen what happens when we fail to react quickly to an emergency). In a discussion on the lessons COVID-19 can teach us about how to face climate change, a 2021 paper says it best:

“The pandemic and global climate crisis both underscore the profound interdependence between humanity and biodiversity, such that the natural world’s vulnerabilities are our own vulnerabilities.”

It’s still too early to trace all the impacts that these pandemics may continue to precipitate. We ache together with this earth; but amidst the wildfire and the inclement weather, the cyclone and the virus, we may begin to take large and necessary strides towards healing.