By Jamie Sibley Yin

Dr. Valerie Loeb is an adjunct professor at Moss Landing Marine Labs. Currently, she functions as an independent Antarctic ecosystem research scientist collaborating with Jarrod Santora of UC Santa Cruz. In April, she headed out to sea with a new NSF funded project entitled “Pilot Study: Addition of Biological Sampling to Drake Passage Transits of the ‘LM Gould'”. The following are updates from the field by Jamie Sibley Yin who is in charge of communications.

April 22, 2015

When we unlatched the cod end from the net, gobs of krill poured over the top, I scrambled to catch the wriggling animals in a bucket. The boat was en route to a fish trawling area near Dallmann Bay.

Humpack and fin whales dotted the horizon, seabirds swooped around the bow, plunging into the water to feed. This appeared to be a very productive region especially when coupled with a strong signal from the acoustic Doppler current profiler (ADCP). ADCPs send sound through the water column where it is reflected by sound scattering organisms such as crustaceans and fish with swim bladders. The ADCP at our current location showed a thick layer of nektonic organisms close to the surface. These creatures were most likely attracting the whales and birds, but the only way to know for sure was to conduct some net tows in the area. In contrast to our other tows, which were full of salps, copepods, and chaetognaths, every tow we pulled up was dominated by large Antarctic krill (Euphausia superba). Krill are a vital component to oceans worldwide, as they provide the link between primary production (phytoplankton) and higher-level organisms such as fish and whales.

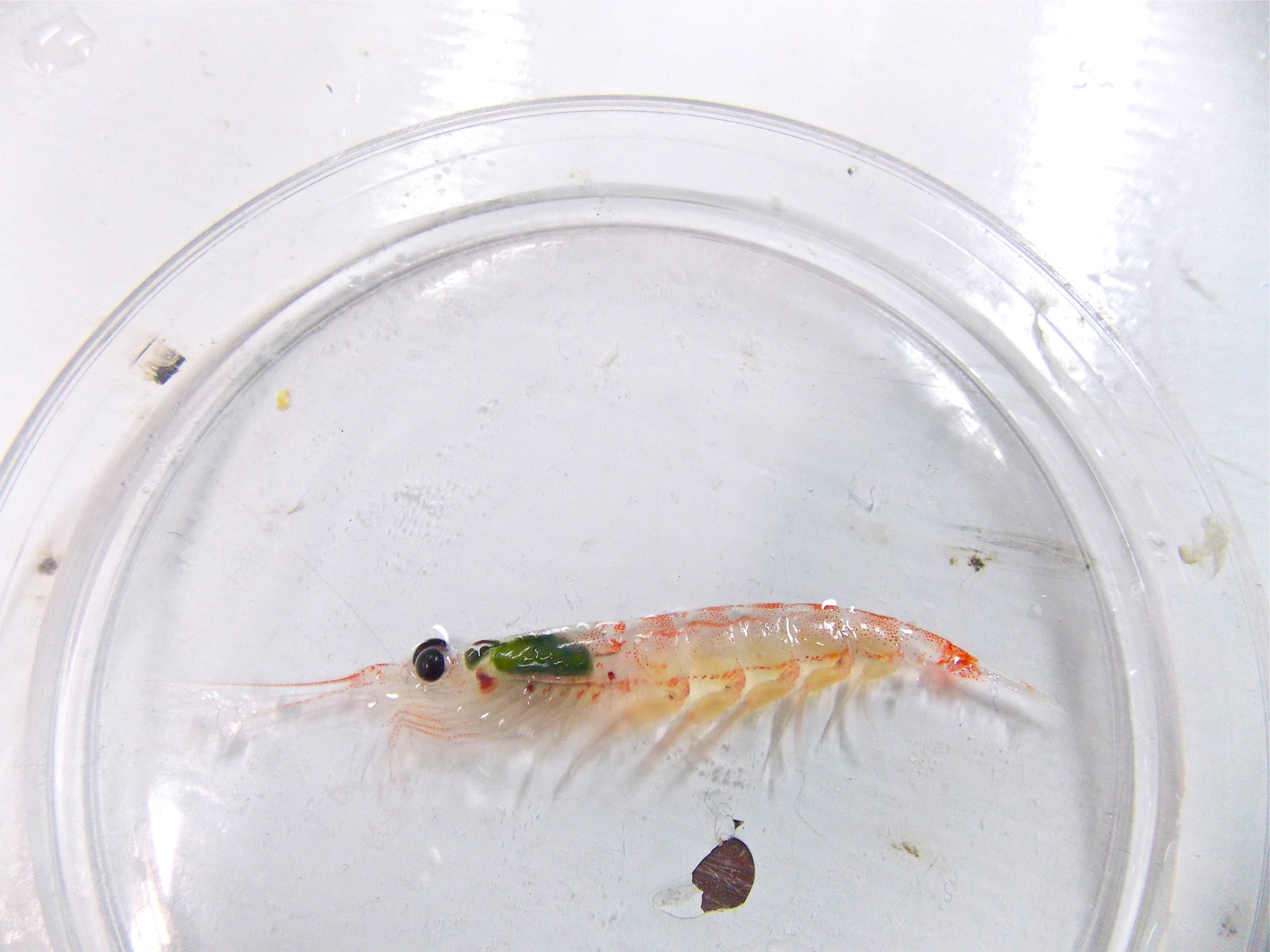

We process our samples as soon as they hit the deck. Part of this is measuring krill body lengths. I take out a sample I had stuck in the fridge before dinner. I’m surprised the krill are still alive, swimming on their side around the clear plastic container, their little legs moving furiously. By the time I’m counting chaetognaths and pulling out amphipods, most everything is dead or feebly waving a pleopod. I’m taken aback by the still swimming krill. I pick one up and plop it in my petri dish, it twitches and flicks sea water at me. It’s large dark eyes jerk--I sense that it sees me. I quickly hold it to the ruler, record its’ length and gently place it in another jar, I add a few ice cubes for good measure, the krill buzzes around. I feel a twinge of satisfaction. After measuring a subsample I dump the remainder over the side, secretly hoping a few survive.

I’m not alone in my admiration for these robust critters. It was once thought krill could provide a solution to world hunger as they are abundant, low on the food chain, and a good source of protein. Unfortunately their chitin proved hard to remove, and they ended up having toxic levels of fluoride in their tissues. They have been used as cattle and poultry feed, and for farmed salmon to emulate the pink color of their wild counterparts. This pink color is from beta carotenes in the krill’s carapace, which also accounts for the pink feathers of flamencos, who feed on fresh water euphausiids. The latest fad is krill oil-- toted as a health supplement. After reflecting on the great utility of krill, I didn’t feel so silly throwing them back.