By: Paul Tompkins

MLML Phycology Lab

PhD Candidate

Leibniz Center for Tropical Marine Ecology (ZMT)

Photo by: Paul Tompkins

After my master's thesis was accepted in the fall of 2011, I began applying for PhD positions. I was accepted at the University of Bremen's Center for Tropical Marine Ecology. My current advisor, Dr. Matthias Wolff, leads the resource management working group within the department of ecological modelling. He has spent many years studying the highly productive waters along the Pacific Coast of South America, and is currently leading a project in the Galapagos archipelago. The goal of this work is to understand how upwelling influences the tropic structure of the islands, and to use this understanding to inform fisheries management in the face of climate variability. My role in this project is to describe the biogeography of macroalgae around the Galapagos archipelago, and determine the functional role of these primary producers in the Galapagos marine tropic web. Of particular interest is the influence of upwelling on algal species distributions, community structure, and productivity.

I have now been in living in Puerto Ayora for two months. During my first week here, I was living on the R/V Queen Mabel, with collaborators both from ZMT and the Charles Darwin Foundation (CDF), and surveying the Islands of Darwin, Wolf, Pinta, and the East coast of Isabella. To estimate the percent coverage of macroalgae, I used sampling protocols were similar to those used by the CDF’s ecological monitoring project. At each site, a 50 meter transect was laid parallel to the shoreline at depths of 15 and 6 meters. Every five meters along transects, a 0.25m2 gridded quadrat with 80 intersection points was placed on the seafloor, and the primary substrate was recorded.

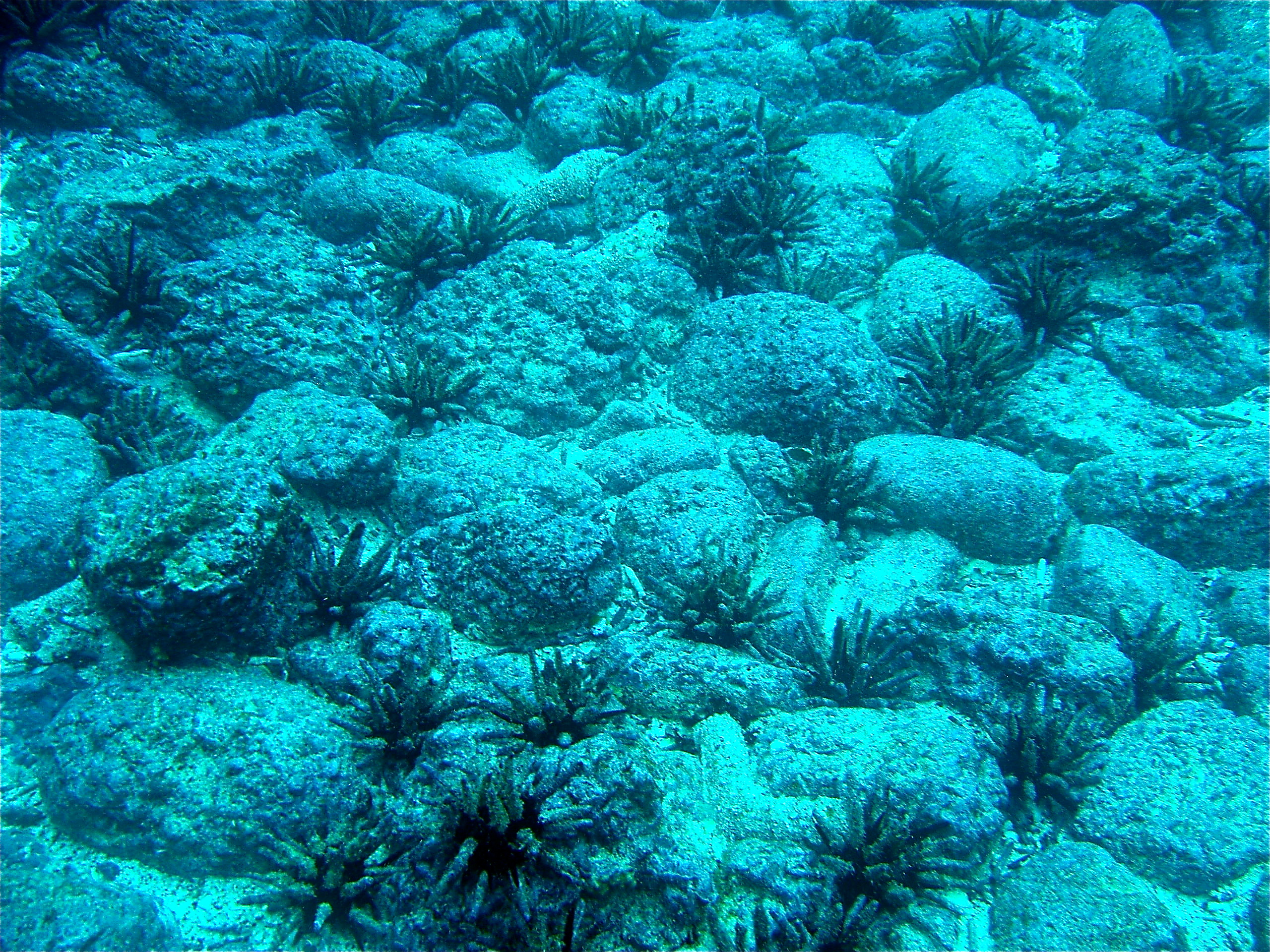

These data were converted to percentage cover, and the general trends were as follows: Crustose coralline algae (including genera such as Lithothamnion, Lithophyllum, Sporolithon, Titanoderma) were the dominant benthic species, often covering more than 50% of the available substrate. Sessile invertebrates such as corals, sponges, and tunicates were also abundant, with corals sometimes covering 100% of available space in the quadrats, though with high variability (often there was no coral at all). Filamentous green and red algae were often recorded (species TBD), and competed for resources with algal genera such as Dictyota, Lobophora, Hildenbrandia, Bryopsis, Lyngbya, and Padina (listed in order of decreasing occurrence).

Overall, the locations sampled so far seemed to have relatively low macroalgal diversity, biomass, and productivity. The macroalgal species lists maintained by the CDF contain over 300 species, but relatively few were seen on this trip. Coralline algae precipitate calcite and grow very slowly, and therefore, per unit biomass, do not contribute to productivity as much as erect, fleshy, fast-growing species. Most of the other macroalgal species surveyed were crustose, mat-forming, or filamentous, and their contribution to the structure of the reefs seemed to be minimal. However, an incredible abundance and diversity of vertebrate and invertebrate herbivores was seen (limpets, urchins, parrotfish, turtles, etc.), and grazing scars were common on the crustose corallines and corals.

High grazing pressure may be keeping the algal species (particularly fleshy, erect species like Bryopsis) in check, and limiting their competitive potential in this system. The sea surface temperatures at our survey locations were also relatively warm, and did not vary much from 24°C. We had anticipated the waters around Isabella to be much colder, as the upwelling season in Galapagos should be in full swing. However, Puerto Ayora has also seen heavy precipitation during what is normally the dry season here. Studies elsewhere have shown the abundance, diversity, and community dynamics of faster-growing, more ephemeral species of macroalgae to be influenced by short-term environmental variability, and should the Galapagos archipelago be now experiencing anomalous meteorological and oceanographic conditions, the ecology of faster-growing, more ephemeral species of macroalgae could be much affected. As usual, more work is needed to understand the relationships between macroalgal ecology and environmental changes in the Galapagos.

Some non-macroalgal highlights from the trip included the dives where we found ourselves surrounded by hammerhead sharks, which were often hidden behind incredibly dense schools of “gingos” (Paranthias colonus) (small, planktivorous reef fish that were a ubiquitous part of our diving experience). Manta, eagle, and marbled rays, sea lions, green turtles, abaco jacks, and octopus were seen, some on almost every dive. Reef fish, most notably large schools of razor surgeonfish (Prionurus laticlavius), continually surrounded us. At the end of our last dive, at Isla Sin Nombre, Claire Reymond, Diego Ruiz, and I shared the experience of a lifetime as a huge school of endemic Galapagos sharks swam just beneath us. Just prior, I had somehow managed to drop my mask and lose my regulator. I'm such a good diver....

Photo by Paul Tompkins

Since the voyage to the Northern islands, I have been working with Dr. Frank Bungartz and Nathalia Tirado to verify and update their virtual database, specifically (of course) information about Galapagos macroalgae. Concurrently, I have been surveying more local sites, reviewing all of the macroalgal literature held in theCDF's library, and preparing my national park permits for next year.

Photo by: Paul Tompkins

I was lucky enough to be given some desk space at the BIOMAR building. Above is the view from my window, and just outside a colony of about forty marine iguanas tromps to and from the water everyday to forage at low tide. I wonder what they're eating.....

Photo by Paul Tompkins